Roots beyond research: A garden that grows more than plants

At CERes, we believe growth is not only measured by experiments completed, hours spent in libraries, or papers published — it can also take root in the soil. Our InchbyInch community garden has become a place where early-career researchers cultivate not only vegetables, herbs and flowers, but also connection, well-being, and a sense of balance.

The InchbyInch community garden

The project, launched in 2019 with the support from the DAAD (German Academic Exchange Service), initially had a straightforward purpose: to help international doctoral researchers put down roots in a new country — roots that extend beyond the academic environment and foster belonging within the local community.

Over the years, the garden has flourished. Today it invites all doctoral and postdoctoral researchers to become part of a community that values well-being, a healthy work-life-balance and the joy of reconnecting with nature. Each season runs from late April to early November, beginning with an information event at the end of April, where (new) participants can meet the gardening team, ask questions, share ideas, and plant their first seedlings. Throughout the season, CERes provides guidance, resources, and opportunities for social gatherings in the garden.

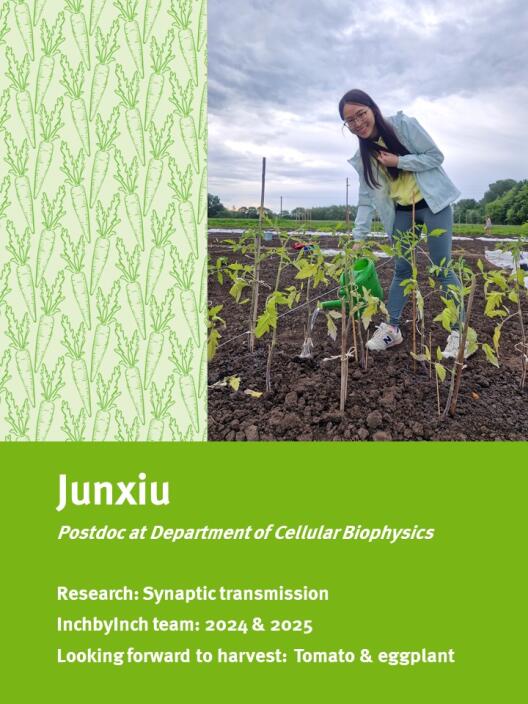

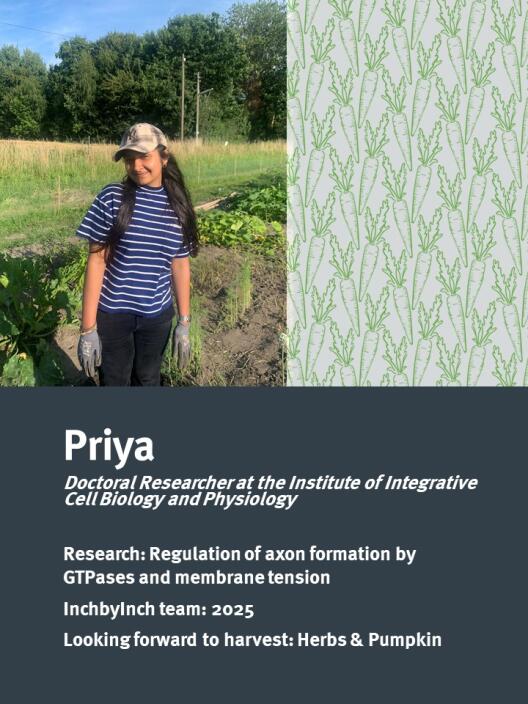

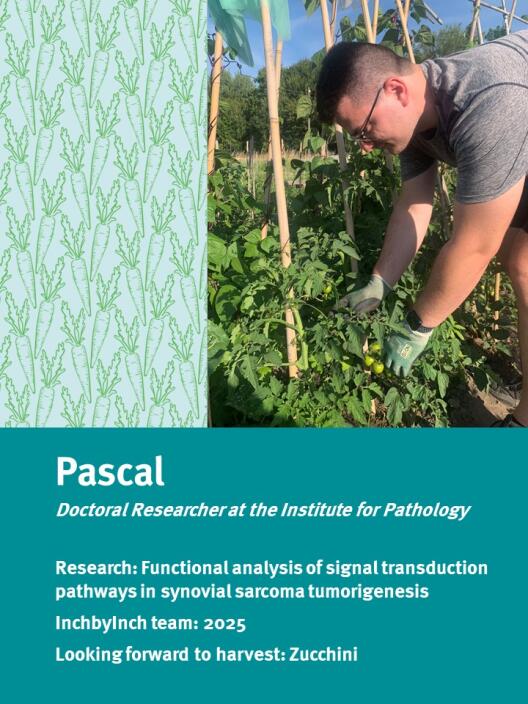

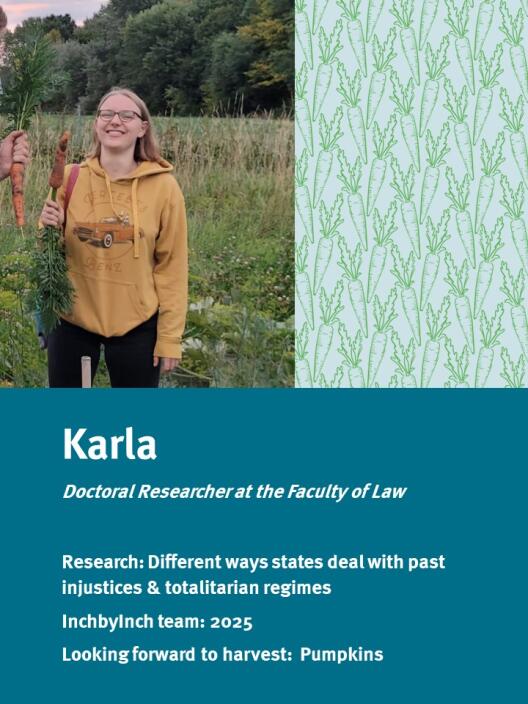

This year, eight dedicated researchers are tending to a shared plot of organic vegetables, herbs, and flowers. We spoke with five of them about how the garden has shaped their academic and personal growth — and how nurturing the soil together has sparked fresh perspectives beyond the greens they grow.

The interviews have been conducted in July 2025, in English or German and the responses are presented in the original language to preserve authenticity.

What first inspired you to join the Inchbyinch community garden?

Karla: In my research field — law — everyone is working on their dissertation project on their own. In the garden, it is the opposite because you work in a team and have to coordinate all the time. I thought it would be nice to get to know more people, have a community, achieve a common goal, take care of the field, and then, eventually, harvest the fruit(s).

Junxiu: Lakshmi and I had just finished our PhDs and we finally had a little bit of time to think of work-life balance and then this idea comes ahead and sounds like a lot of fun.

Do you have a favourite moment or story from your time in the garden that you would like to share?

Pascal: Einfach, dass es schön ist, dieses Zusammenkommen und sich dann gemeinsam zu überlegen: Was machen wir heute? Und dann kann man vielleicht noch etwas ernten — eine kleine Belohnung, die man mit nach Hause nehmen kann.

Lakshmi: Whenever I bike back with all these veggies and then when you are in the wind, it's like re-prioritising. And then you look in the basket and see the literal fruit of all your hard work.

If you could compare your research journey to a plant or a gardening process, what would it be and why?

Priya: Once, I was all alone and I was weeding and I got lost into the weeding process and I realised when I do research, when I do my cell culture experiments — it's the same. I just get lost in the moment and I thought, okay maybe I love gardening as much as I love research. It's a very similar process: the weeds come back, they annoy you and my experiments fail and they annoy me.

Junxiu: They have some similarities. For example, when we start gardening, we see nothing and think, “Oh my god, can we really make it?” You look at the soil and wonder, “It's so hard — can anything grow here?” I think it feels pretty similar when you start a PhD, entering a new lab, a new environment, a new culture and you think, “Oh my god, can I make it?” A lot of things are new and a lot of things are unknown.

What is the most surprising thing you’ve learned from gardening that you wish you'd known earlier in your academic career?

Priya: This gets a bit philosophical. When I started my PhD, the first two years were quite difficult as I tried to adjust to new experiments. I didn’t know much about them at first, and it was frustrating. I needed an outlet to relax, so I joined here. It made me realize the value of commitment — you keep coming back, doing things regularly. Initially, I couldn’t contribute much because I joined later, but recently I’ve been doing some weeding, not as much as them (pointing at Junxiu and Lakshmi) and it made me feel truly involved. It’s similar to the PhD; both teach patience and commitment. So, I think gardening has been very important for me in that way. I love it!

In both research and gardening, setbacks are inevitable. How do you handle “failed experiments” or surprises in the garden, and has this helped you deal with challenges in your research?

Pascal: Ich würde es eher umdrehen. Ich bin schon länger in der Forschung tätig und habe bereits vorher Laborerfahrung gesammelt, da ich vor meinem Studium eine Ausbildung zum BTA (Biologisch-technischer Assistent) gemacht und fünf Jahre in diesem Beruf gearbeitet habe. Ich weiß, wie das mit den Experimenten und möglichen Fehlschlägen läuft. Deshalb ist das für mich im Garten jetzt nichts Neues.

How has participating in the community garden affected your work-life balance or well-being? Are there specific ways it has helped you manage the demands of academic life?

Lakshmi: Once you're really into doing something, I think, it's really hard to stop. Maintaining a work-life balance can be difficult, and sometimes the pressure is not external – it comes from you. Having something to look forward to outside the lab is really valuable, especially since, as foreigners without family here, most of our friends are from the Graduate School and work late. The community garden gave us a reason to leave the lab, and it was easier to stay committed because Junxiu and I always went together.

What has it been like working alongside researchers from other fields in the garden? Has it changed your perspective or approach to your own work?

Karla: I once worked alongside an archaeologist and it was interesting because I had no prior insight into that field. I found a stone that seemed random to me but she immediately identified it as dating back to an older farming era. It was a cool moment when I realised that we were farming in the same spot as people had farmed years ago. And generally, working with the others provided me with a lot of insights into how different fields have very different approaches and that the way we do it in law is not the only way.

What do you think makes for a joyful and successful gardening season as a team?

Karla: I think the answer is already in the question — it's a team project, and you have to coordinate well. For example, not everyone should only go on weekends, but also during the week. It's important that everyone does their part, stays motivated, and finds joy in going regularly — not just at the start with the initial motivation, but throughout the whole season. In the beginning, doing a lot of weeding together really helps. Right now, the garden is growing really well. I think we did a very good job. The plants are big, and there are very few weeds. I think we've managed this season quite well and it's been both joyful and successful.

Who would you recommend to join the Inchbyinch community garden project, and what do you think they would gain from the experience?

Lakshmi: I would encourage people from all phases of the PhD but especially those who are just starting their PhD. It really helps maintain a healthy work-life balance, which is essential. When you set your own rhythm, you're less influenced by external factors. I'd tell them that one of the biggest benefits is the sense of accomplishment it gives. In the lab, things often don't work, and in academia, mistakes can feel very personal because your project feels like an extension of yourself. Having other areas where you can achieve and feel fulfilled makes a huge difference.

We are extremely grateful to Larissa Mrwa, who passionately coordinated the InchbyInch garden in 2024 and 2025 and whose engagement in conducting the interviews was essential in making this story happen.

Perplexity and DeepL Write were used to refine the introduction text and to brainstorm and formulate the interview questions. The resulting interview draft was adapted by Larissa Mrwa and Sabine Schneider, discussed with the CERes team, and adjusted accordingly.