University museums: positioned between research, teaching and the public

The re-opening of the Archaeological Museum and the Bible Museum at the University of Münster enriches the museum landscape in a city steeped in science and culture, as well as extending university research and teaching to the public in a new and innovative way.

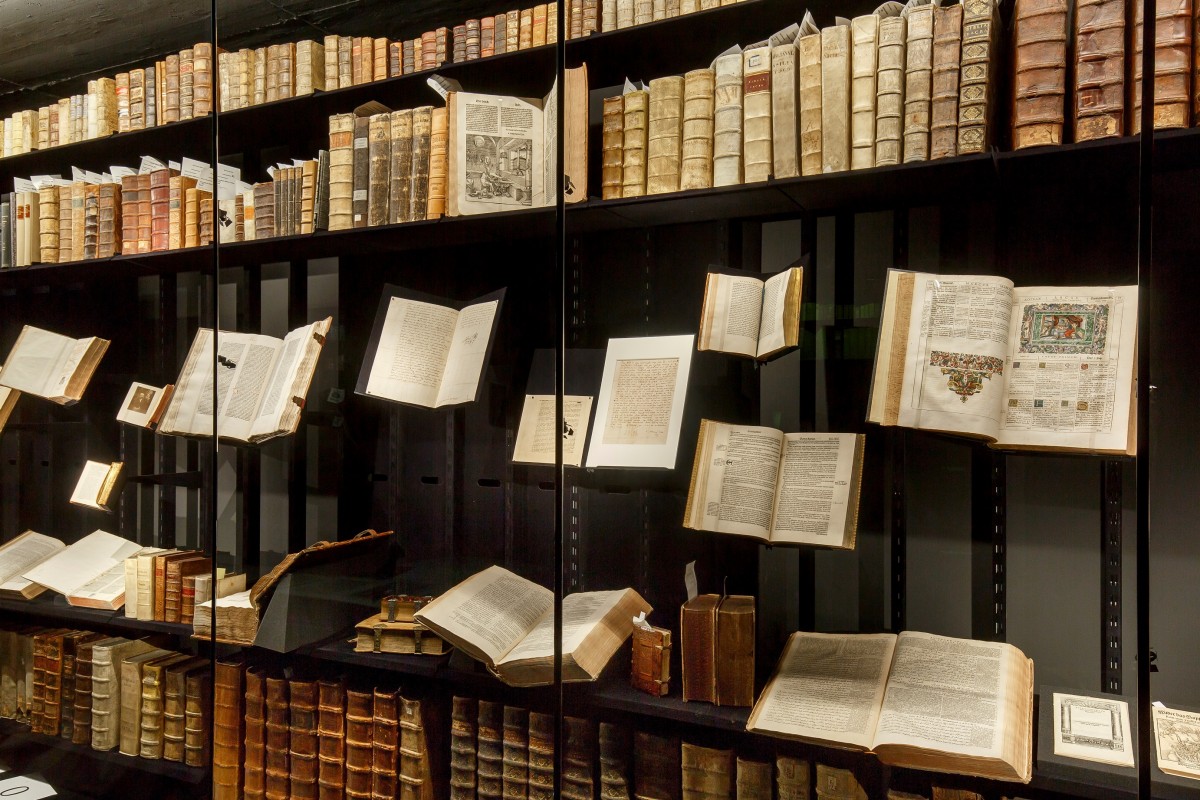

Both museums have impressive collections. The Archaeological Museum has on display a significant collection of casts of well-known sculptures, as well as models of important sites of antiquity. The Bible Museum is deemed to have the most comprehensive collection in Germany relating to the history of the Bible, and it documents the New Testament from its beginnings in manuscript form up to the present day, all based on over 700 Latin, Greek and Syrian-Aramaic editions of the Bible.

University museums have a variety of tasks. First of all, their collections have a teaching purpose because they provide students with haptic experiences of stone and metallic objects or of various types of pottery – which, especially in prehistoric archaeology and in the area of pre- and early history, is indispensable for a deeper understanding of how things were made and worked. Classical archaeology, on the other hand – which has traditionally had a stronger art-historical orientation – has always worked with casts of masterworks of antique sculpture for teaching and training purposes, thus making sculptures accessible in a three-dimensional way.

A few years ago, Germany numbered 79 university collections focusing on archaeology, with 31 of them covering Classical Archaeology and 22 professorships for Prehistoric Archaeology. Their situation is, in most cases, precarious. Often there is a lack of specialist staff for academic work and conservational care, financial resources are inadequate, and in most cases there are no suitable rooms for exhibitions to attract the public. As a result, university collections often lead a shadowy existence, are not very accessible, and do not receive proper attention from the public – or, indeed, from the relevant university itself.

Fortunately, none of this applies to Münster. Nevertheless, the museums at Münster University face a twofold challenge. They have to find and assert their role not only within the university, but also within the museum landscape. A key role is played by being involved in current debates – for example, on the issues of provenance research and restitution. Münster University did this in a particularly exemplary fashion when, in the summer of 2018, it returned a marble Roman head to Italy. The head had been acquired for the University Museum in 1964, but just recently it was discovered that it had been stolen from the Archaeological Museum of the town of Fondi, in central Italy. Returning the item was the right and proper thing to do.

As a rule, the teams working at university museums are small, and this alone means that they cannot compete with public museums. This applies for example to the question of opening times, which depend on the availability of museum attendants, as well as of further infrastructure such as cafés, shops and so on. For these reasons, university collections should enter into strategic alliances with public museums, all the while reflecting on their strengths. There is much potential in collaborating on exhibitions, in setting up thematic networks, and in a greater emphasis on research aspects. Unique selling points include aspects such as exhibiting research results, citizens science, and participation: university museums are showcases for research.

Other museums elsewhere face similar challenges – in Berlin, for example, with the development of the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation’s Dahlem research campus with the State Museums at Dahlem. With the Freie Universität Berlin close by, the aim is to achieve a new quality in the specialist content shared between the university and the museum.

The Bible Museum at Münster is part of the University’s Institute of New Testament Textual Research. It makes research into the history of the Bible, and the reconstruction of the original text and the variations in it, both accessible and attractive to the general public. In doing so, it uses a wide range of offers for schools and other target groups and also includes innovative applications such as virtual reality. In addition, the museum has become an established location for interreligious dialogue. This is how museums become living platforms for exchanges and debates.

The University of Münster’s Archaeological Museum and Bible Museum have found an optimum location. Together with the LWL Museum Art and Culture, a splendid museum quarter can now evolve on the edge of Domplatz which will link the University and the city in a new kind of way. This will be contingent upon the different, though complementary, competences which LWL and the University have – as a result of their respective profiles – being combined in a manner which benefits both sides. Achieving this will be the real challenge.

Prof. Hermann Parzinger is President of the Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz.