New international project on stroke research

According to the Robert Koch Institute, strokes are among the most frequent causes of death in Germany, along with heart diseases and cancer, and they are the most frequent cause of permanent disability in adults. Every year in Germany, around 200,000 people suffer a stroke. A new research project headed by biochemist Prof. Lydia Sorokin from the University of Münster will investigate functions of different barriers in the brain and how they are altered in stroke. The project investigates not only the blood-brain barrier that separates the blood circulation from the central nervous system, but other barriers at the surface of the brain and between the cerebrospinal fluid and the brain.

The project – entitled “DeCoDis – Deciphering Cellular and Acellular Barrier Dysfunction in Cerebrovascular Diseases” starts in July and will receive 850,000 euros in financial support for three years from the German Ministry of Education and Research as part of the EU network “ERA-NET NEURON”. Taking part in the project will be scientists and researchers from the Charité Hospital Berlin, the University of Bern in Switzerland and the Center of Immunology Marseille-Luminy in France.

Details of the project

So far, treatment after a stroke has aimed at preventing circulating white blood cells from penetrating into the brain – but with little success. Lydia Sorokin’s team is taking a new approach: “Our aim,” she says, “is to find out precisely which barriers are damaged as a result of a stroke, and how we can subsequently restore their function.” The team will examine how these barriers contribute to the penetration of harmful immune cells after a stroke and how the disruption to their proper functioning contributes to the accumulation of fluid known as a cerebral oedema. Understanding these connections will enable the researchers to develop new strategies for treatments that stabilise the function of the relevant barrier after a cerebral infarct, thus, reducing damage to the brain and enhancing chances of survival.

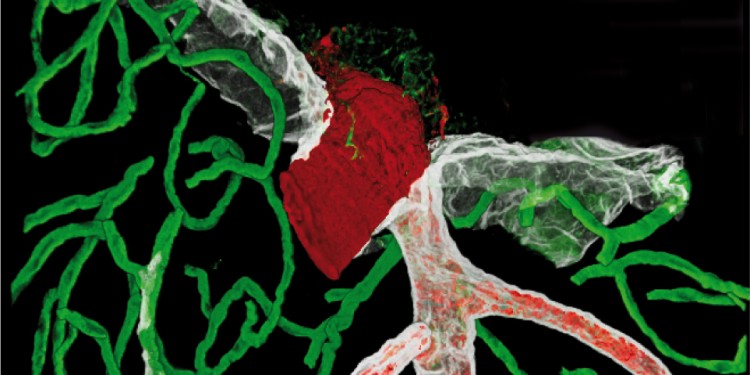

The researchers will study processes taking place at the different brain barriers in genetically modified mice. With the aid of special microscopy techniques – so-called intravital microscopy – they will be able to visualize in a living organism how immune cells interact with the brain barriers, and they can analyse how the function of the barrier changes in stroke. “In this way,” says Lydia Sorokin, “we can identify different factors which change the properties of the brain barriers and subsequently validate them in samples of human brain tissue taken after a stroke.”