“Trust is the most important thing”

Uncovering the secrets of the universe: this is one of many aims which CERN (European Organisation for Nuclear Research) in Geneva has. With its 23 member states and around 3,400 people working there, CERN is the world’s largest research centre in the field of particle physics. More than 14,000 visiting researchers from 85 countries are at work on CERN experiments. One of them is Prof. Christian Klein-Bösing from the Institute of Nuclear Physics at the University of Münster. One of the things he is working on is the ALICE project (A Large Ion Collider Experiment) – one of the four major experiments being undertaken at CERN’s Large Hadron Collider (LHC) and, with its 27 kilometres, the largest particle accelerator in the world. In this interview with Kathrin Kottke, nuclear and particle physics expert Christian Klein-Bösing explains what precisely the project is about and what collaboration is like in a large international team.

What is your research all about?

I want to understand the components of matter. They’re the smallest particles which we know so far, and they’re the basis of the entire visible universe and life on Earth. You have to understand that matter is composed of atoms, which consist of atomic nuclei and electrons. Atomic nuclei, for their part, have even smaller components – protons and neutrons, which consist of so-called quarks.

And it’s these quarks that you want to investigate?

Exactly. However, we can’t just simply observe them. Isolating quarks is a very complex process which requires special technological methods. In order for quarks to be able to move freely, we have to heat up the atomic nuclei until they dissolve. To do that, we need very high temperatures – but we can only achieve these if the nuclei smash into each other with such force that they dissolve into their constituent parts.

And that’s where CERN comes in?

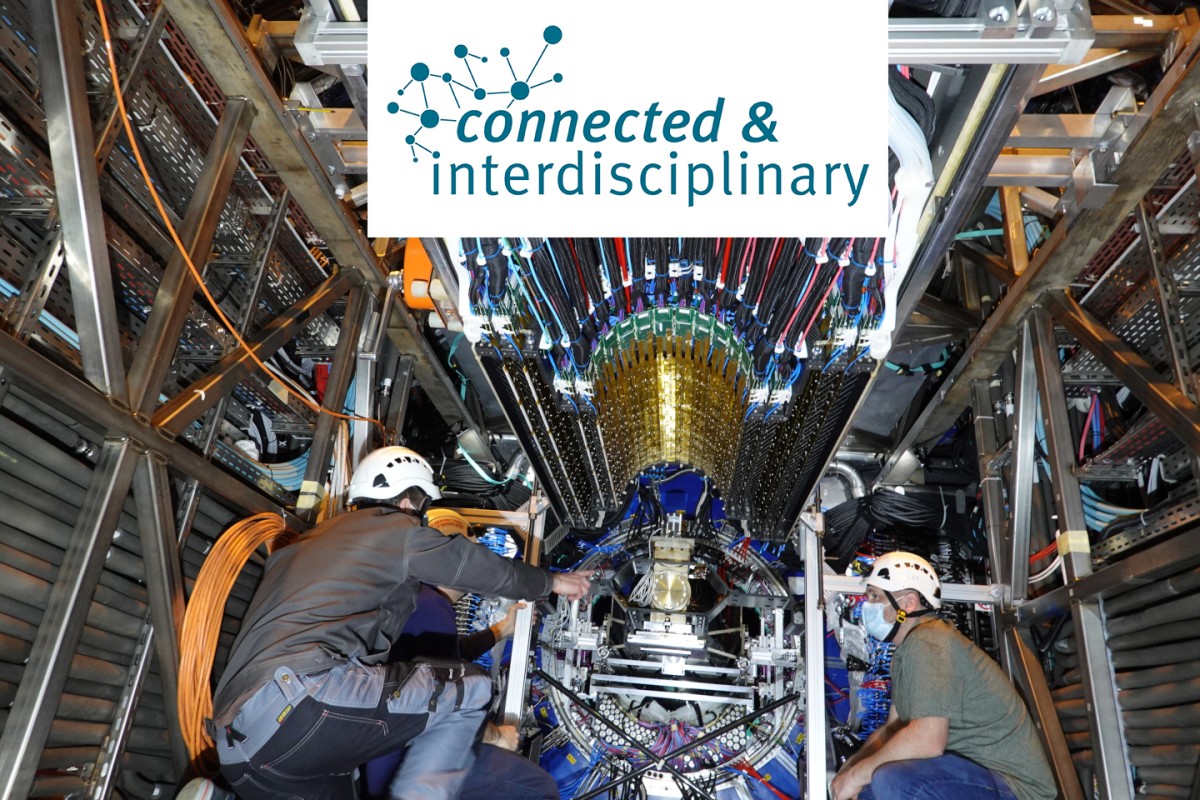

We’re carrying out our experiments with the ALICE project at CERN. It’s a multipurpose detector which is optimised for collisions between heavy atomic nuclei – lead, for example. In such a collision – for just a fraction of a second – the matter is in a state such as existed immediately after the Big Bang.

Presumably you need a lot of experts with a variety of competences to carry out these experiments …

Absolutely. As just a particle physicist I wouldn’t get very far by myself with my questions and experiments. Collaboration between individual disciplines is indispensable – for example physics, chemistry, materials science, computer science and mathematics – but so is the expertise contributed by the technical staff and engineers. Taking a wider view beyond the boundaries of my own discipline motivates me every day and gives me a lot of pleasure.

Can you give us an example of why interdisciplinary collaboration is so important?

A few years ago we had to solve a technical problem as a tiny condenser was broken on one of the detectors. Initially, we were afraid that we would have to completely dismantle the detector in a very laborious process. Then the technicians suggested that we could use a milling process on the metal sheet at the side and peel it back – like opening a tin can with a ring-pull. We were able to take the condenser out and seal up the metal sheet again. That was a nice joint effort, and something I would never have thought of myself.

With around 2,000 people working on it, ALICE is one of the largest single experiments at CERN. It sounds like a mammoth task, organisation-wise …

Planning and management take place at different levels. Around 600 physicists are working on the ALICE experiment alone. Scheduling agreements are crucial, and many meetings take place digitally nowadays – nevertheless, I’m there on site once or twice a year. The experiments which take place with the big accelerator (LHC) are scheduled years in advance, with collisions between heavy nuclei always being carried out in the November and December of every year, for example. But there are also smaller experiments at CERN that you can integrate your own experiments with, and which require a smaller lead time.

Do you have to be present for all experiments?

Not necessarily. A lot of the data generated in the experiments are made available to us digitally, and we can analyse them in Münster. Some tasks, on the other hand, require our presence. For example, occasionally we have to repair our detector or carry out maintenance work on it, and that is only possible on site. Or when the collisions in ALICE are being recorded, the entire experiment has to be monitored 24 hours a day over several weeks – and, at such times, every member of the ALICE team has to work shifts at CERN.

There’s an old saying: too many cooks spoil the broth. Who makes the decisions at CERN?

The highest body is the CERN Council, in which 23 member states are represented who make decisions. These states have made a commitment to contribute funding to the CERN budget as a proportion of their GDP. The budget is around one million Swiss francs. There is an elaborate system in place which ensures that investments flow back to those countries which invested the money.

There is also a number of other bodies. For ALICE, for example, there is the Collaboration Board, in which every institute is represented. This Board appoints further bodies with responsibilities for different areas – for example physics, technology, publications or PR work. Then there are yet more subsidiary groups for certain topics, for which a chair and other representatives are elected.

That sounds like a lot of bureaucracy …

It is, to a certain extent. But it can’t be done any other way, unfortunately. There is one special challenge in all this, and that is that nobody is bound by instructions. Under labour law, for example, I am bound to the University of Münster, and not to CERN. At CERN, almost everything depends on the individual sense of responsibility of the people who work and do research there.

That also assumes a large amount of trust, I suppose …

It doesn’t matter whether we’re talking about dealing with technology, with data or with other people: trust is the most important thing.

Is there any special memory you have of CERN? Or of any special meeting?

Before I started at the University of Münster in 2008, I was employed for two years at CERN as a member of the research staff. During this time, I presented my research in a colloquium – in the lecture room in which the so-called “Higgs Discovery” was later announced. An elderly gentleman asked me a lot of interesting questions during my talk. Afterwards we went to the cafeteria and continued our discussion. I had no idea that I was talking to Nobel prize-winner Jack Steinberger. That was a great honour – and a special memory I have.