The Banner of Péronne – a political matter

As journalists traditionally say: real-life stories are the best ones. In the case of Dr. Daniel Stracke, 46, an historian and research assistant, his real-life story presented itself in the corridor of the Institute of Comparative Urban History (Institut für vergleichende Städtegeschichte, IStG) at the University of Münster. This is where, over ten years ago, Stracke’s research – painstaking and at times shrouded in mystery – began. Eventually, it led to finding the historic Banner of Péronne, which had been lost since the First World War. Doggedly pursuing his research, Stracke was able not only to place the Renaissance tapestry in Péronne in Picardy, north-west France, but also to trace the journey the Banner took.

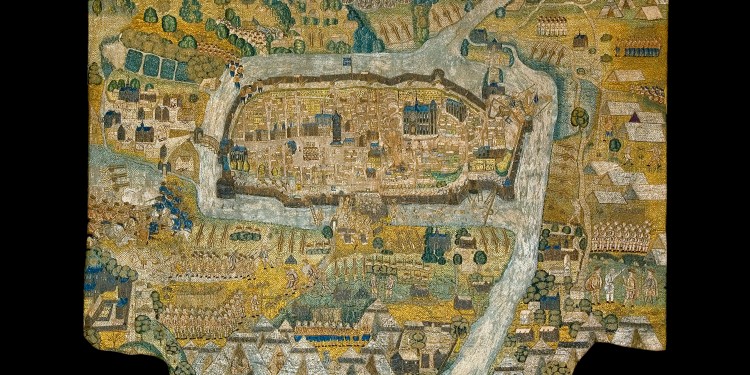

The tapestry, which Stracke initially only saw in a photo, shows an historical scene, from above, of the siege of a town. The 16th-century piece is elaborately made, with silk embroidery interspersed with threads of gold and silver. It is not hard to see that the context in which the tapestry was made must have been a significant one.

There is now another pause in the continuation of the story because no answers could be found regarding the path travelled by the Banner in wartime. However, Daniel Stracke’s intention is to help shed some light on the issue and even perhaps give back to the citizens of Péronne a piece of their collective memory. “It has now become a political issue,” says Stracke. His work has been very much like that of a detective. As Dr. Angelika Lampen, who heads the IStG, says: “The researcher’s tenacity and the competence that characterise our Institute – as well as the collections and the research possibilities that we have – have all come together in Daniel Stracke’s work. It is especially gratifying that the solution to the mystery could be made public in the year we celebrate our Institute’s 50th anniversary.”

The painstaking provenance research had begun with the photo of the tapestry mentioned above, which an elderly man brought to the Münster University-affiliated Institute around ten years ago. His son, a London antiques dealer with Westphalian roots, had bought the historic tapestry at an auction but didn’t know which town and which siege it depicted. Nor could the exact value of the Banner be ascertained.

Because of the many bequests it has received, the Institute has in its possession literature and maps which no other library in Münster has. In the end, Stracke found the decisive clue in a little French book containing descriptions of medieval town halls and their belfries (“beffrois”). “These watchtowers and belltowers – either attached to the town halls or free-standing – were an expression of the power of the mercantile class in the late Middle Ages, from the Netherlands to northern France,” Stracke explains. In a little guide to architecture entitled “Hôtel de ville et Beffrois. Nord de la France” (“Town Halls and Belfries. Northern France”) he finally found the characteristic tower which he knew from the tapestry: it was the belfry of Péronne.

Having ascertained the location of the Banner, the next step was to find out the date, the story of how the tapestry came to be made, and its fate. Looking through other history books, Daniel Stracke made out the scene on the Banner as the siege of Péronne by Charles V, the last Habsburg Holy Roman Emperor, who reigned from 1530. After Charles’ rival, the French King Francis I, had routed him and recaptured Péronne in 1536, however, the tapestry was made as a sign of the victory and for a procession of thanks years later.

Exactly 380 years later, during the First World War, the Banner disappeared from the museum in the town hall which had been hit by shells. At that time the town was occupied by the Germans. This gave Daniel Stracke no rest. Eventually, he read in old publications of the accusation that the museum had been plundered. Could the tapestry be a stolen work of art? For him, this was reason enough to continue with his research because the art dealer who had the tapestry in his possession wanted to see proof.

Stracke first travelled to Péronne in a private capacity and, in the “Historial” World War Museum, he actually found an old yellowed photo with the Banner on a wall. “This was irrefutable evidence that the tapestry was in the town hall before the war.” At the same time, the thought that he might have discovered a case of a stolen work of art almost made his head spin. First of all, though, what he had found was enough to convince the new owner of the provenance of the tapestry, and that it belonged in Péronne.

In the spring of 2019, Daniel Stracke travelled to the TEFAF Art Fair in Maastricht, where the world’s largest and most important galleries and art dealers gather every year. The Banner was brought from London and displayed there for the first time in 100 years. Also, Stracke publicly announced the results of his research – which attracted both interest and acclaim. Representatives of Péronne were also invited, but no one came. Was there no interest? Anything but! The news that the tapestry had turned up had already meant that the matter had gone through the courts, and today the French Ministry of Culture and Justice is handling it.

Author: Juliane Albrecht

This article was first published in the University newspaper wissen|leben, No. 3, May 2020.