“Those commissioning the work, as well as scribes, owners and readers – these all shaped the translations and turned the transcripts into a ‘living’ work”

Interview with Islamic studies scholar Philip Bockholt

The research project led by Islamic studies scholar Philip Bockholt at the Cluster of Excellence ‘Religion and Politics’ focuses on one of the most important religious text genres in Islamic culture: Arabic-Ottoman translations of works of Quranic exegesis (Arabic: tafsīr). In this interview, he discusses why translations from Arabic into Turkish were so significant, what adaptations can be observed in the texts during the process of translation, and what role these translations played in disseminating religious knowledge.

What exactly is the focus of your research, and what is your central research question?

Philip Bockholt: My project examines how knowledge was transferred within Islam in the eastern Mediterranean between 1400 and 1750 by studying Arabic-Turkish translations of works in the genre of Quranic exegesis – that is, the interpretation of the Quran by scholars in book form (tafsīr in Arabic, tefsīr in Turkish). The focus is on Mūsā İznīḳī’s early 15th-century Enfesü’l-Cevāhir, the earliest and most popular early modern translation of Quranic exegesis into Turkish. The original Arabic text is Abū Layth al-Samarqandī’s commentary on the Quran from the late 10th century. The aim is to show the role that such translations played in the linguistic and cultural transmission of religious knowledge. My key question here is: To what extent did translations of works of Quranic exegesis into Turkish involve textual adaptations within the broader context of how Ottoman Sunni Islam situated itself?

What sources do you draw on for your research, and how do you access them?

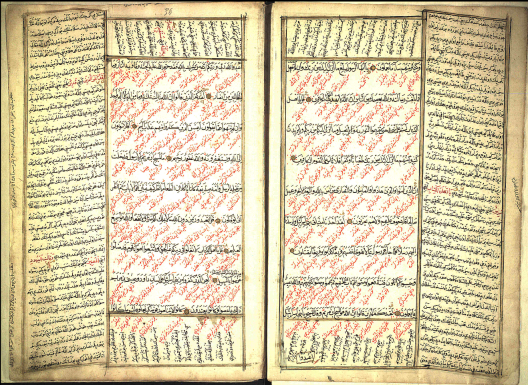

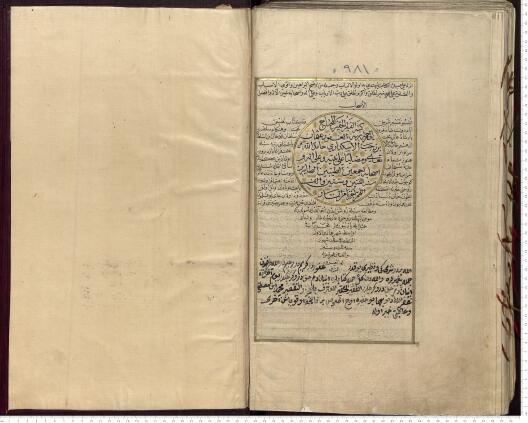

Philip Bockholt: The main sources for the project are manuscripts from the period before the advent of printing, which only became widespread in the Islamic world in the course of the 19th century. In the case of the translation of Mūsā İzniḳī’s Enfesü'l-Cevāhir that we investigate, my doctoral student Ahmet Aytep and I were able to locate more than 600 manuscripts of both the Arabic original and the Turkish translation in collections worldwide, most of which we have reviewed since they are available in digital form. Methodologically, we employ the new philology approach, which considers each transcript an independent textual witness, evaluated both for its content and its paratextual elements, such as colophons, owner and reader comments, and layout. For the analysis, we use Digital Humanities tools such as the web-based text analysis application Voyant Tools, as well as Gephi and Palladio to visualise the network relationships between those associated with the manuscripts.

Who were the Turkish translations of Quranic commentaries relevant to, and why?

Philip Bockholt: At the current stage of the project, we can say that the translations of works of Quranic exegesis were aimed particularly at a broad readership that did not possess the traditional education of legal scholars and whose knowledge was limited by language barriers. This made religious knowledge accessible to wider social groups for the first time – often through adaptations, additions, or simplifications rather than literal translations. Some translations also provided the Ottoman ruling elites with an opportunity to expand their religious legitimacy, thereby combining increased access to education with the consolidation of political authority.

What did this look like in practice?

Philip Bockholt: Just as the general public associated the endowment of religious architecture – such as mosques, madrasas (educational institutions), or public water dispensers – with the name of the person who commissioned the work, so too was this the case with translations of books: the individual for whom a work was translated was usually mentioned prominently in the preface. This practice linked the often well-known and highly valued original work, now in translation, with the name of a member of the Ottoman ruling elite and, in the case of a commentary on the Quran, enhanced his reputation for piety.

In your project description, you mention that you are investigating whether the structure and content of the original texts were retained or altered in any way. Did you find evidence of any ‘manipulations’?

Philip Bockholt: In this specific case – namely, with Mūsā İzniḳī – there was no manipulation in the sense of deliberate changes involving strong theological reinterpretations or religious-political adaptations. The fact that both the author and translator were shaped by Sunni Hanafi Islam played a role in this. However, the translator did adapt the text for a lay audience: he shortened technical details and added his own theological reflections and supplementary information. As a result, the work was not “manipulated”, but rather localised and made accessible to the Ottoman target readership.

What role did the various people involved in the translation process play?

Philip Bockholt: Besides the translator, those who commissioned the work, as well as scribes, owners, and readers, all played a significant role in shaping the translation processes. The commissioners – such as the Ottoman governor Umur Bey in Bursa, whom we have identified as the patron of the translation we are studying – made these works possible in the first place. Scribes and readers, meanwhile, sometimes introduced unexpected changes, corrections, or additions. While scribes might alter the text during the copying process, later deletions or additions in a manuscript can often be attributed to its readers. Buyers occasionally commissioned lavish manuscripts as prestige objects. The interactions among all these actors made the text a ‘living’ work, reflected in the many surviving transcripts.

In addition to the translations themselves, you analyse reader comments, ownership stamps, and other paratextual additions. What insights do these elements offer?

Philip Bockholt: These paratextual additions show us – in the best case – how, where, when, and by whom a work was used. They allow us to trace the geographical distribution, as well as the social reach and dynamics, of the manuscripts. While copies of the Arabic original usually remained with scholars, manuscripts of İzniḳī’s translation were sometimes found in Sufi communities, soldiers’ quarters, or even in the palace – evidence that knowledge was disseminated much more widely when it was available in Turkish.

What makes your research particularly important or relevant?

Philip Bockholt: While the project does not fill all the gaps in knowledge transfer and translation research within Middle Eastern studies, it does shed light on these areas and significantly expands the field of Quranic exegesis for both Arabic and Turkish. The findings also show how religious knowledge was transformed and adapted locally through the process of translation – a field that remains largely unexplored for the early modern period. The importance of translation processes, knowledge transfer, and accessibility is further highlighted by current discussions on AI, which have sparked fundamental debates about access to knowledge, identity, and cultural exchange. In contrast to today – where, until recently, fixed text editions have predominated – translations in the manuscript era were open processes involving many participants. Handwritten texts were, so to speak, living objects, open to continual change within certain limits. Conceptually, the focus was less on literal translation and more on adaptation: translations served not only to change the language, but also to actively create new meaning in different contexts.

What do you find most fascinating about your research subject?

Philip Bockholt: What interests me personally is understanding how people throughout history gained access to information – who actually knew what, when and where, and who, for various reasons, did not. In this case, the source material shows how the process of translation enabled social groups in the eastern Mediterranean to access religious knowledge that would otherwise have remained inaccessible to them, at least independently, without intermediaries. The interaction between translators, patrons, scribes, and readers resulted in the creation of a new, locally anchored body of knowledge in Turkish, based on the original Arabic text but transformed through adaptation and change. (pie/tec)