Luigi Aloisio Galvani: With frogs in search of electricity

This year, we at BACCARA are using the International Battery Day on 18 February to commemorate the Bolognese doctor and natural scientist Luigi Aloisio Galvani (*09.09.1737 in Bologna - † 04.12.1798 ibid.). Galvani did important preliminary work for the development of the battery.

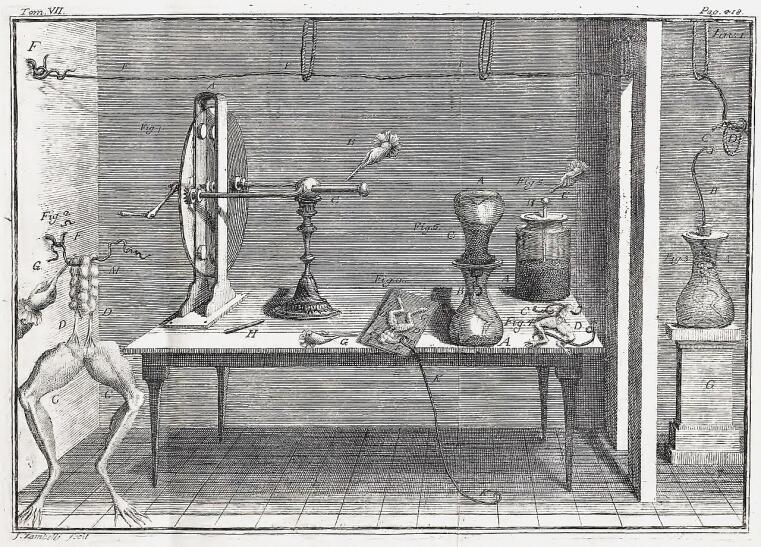

The phenomenon of electricity was not yet fully understood in the 18th century. It was known that friction produced electricity, which led to numerous experiments. In particular, various animal skins were subjected to intense friction in order to bring about the coveted spark. Cat skins and fox tails were particularly popular and there is a pictorial representation showing that live cats were also used for such experiments. For the simpler and more effective production of electricity through friction, an apparatus was finally developed, the so-called "friction electrifying machine". Here, skins could be clamped and rubbed with the help of rotating glass discs. Directly in front of these glass discs, metal tips led to a ball on which the electricity was collected. If this ball came into contact with a conductive object, a small flash or spark could be observed.

According to Galvani, he had such an apparatus on his table on 6 November 1780 when he and his assistants were dissecting and preparing frogs. The dissection and dissecting of nerves using frogs' legs was an integral part of medical training and so it is not surprising that Galvani made use of the pitiful frogs for his experiments. When one of his assistants touched the frog's leg with the tip of a scalpel, the men observed that the muscles and nerves in the cut little leg contracted and the leg twitched. Galvani's second assistant believed to have observed that at the same moment, a spark flew out of the electrifying machine and suspected a connection.

Later, the legend arose that Galvani had the friction electrifier in the kitchen while he was preparing frog leg soup for his wife, who was ill with the flu - a pretty story, but one whose veracity may be doubted. Without a doubt, however, the mysteriously twitching frog's leg gave Galvani cause for extensive experiments. In his search for the electrical connection, Galvani hung frogs' legs on metal hooks around the fence of his terrace to test whether they would twitch again when struck by lightning. Since the frogs' legs did indeed twitch during thunderstorms, Galvani wanted to find out whether this reaction could also be induced without thunderstorms. After days of uneventful observation of the frog legs in calm weather, Galvani finally began to press the metal hooks of the preparations against the iron grid and suddenly the frog legs moved again! Galvani then systematically focused his experiments on the interaction between frog muscles and metals and found that touching the nerves or muscles with an arc of two different metals reliably produced the desired reaction.

Galvani had unwittingly brought about electricity in an electrochemical way. However, he himself interpreted his results differently and believed that, in addition to frictional electricity, there must also be animal electricity and that animal tissue was the source of the detected electricity. At the time of his experiments, articles about the electric eel or electric ray appeared, which makes his thesis comprehensible. The researcher was convinced that he had found a new type of electricity and published his results in 1791 in his paper "De viribus electricitatis in motu musculari commentarius". The German translation appeared in 1793 under the title "Abhandlung über die Kräfte zur thierischen Elektrizität auf die Bewegung der Muskeln". Less than ten years later, Alessandro de Volta disproved the existence of animal electricity. The original form of the battery he developed, a column consisting of copper plates alternately stacked on top of each other and cloth flaps soaked in a salt solution, clearly showed that the source of electricity is in inorganic matter. Volta paid tribute to Galvani's important preliminary work by calling the original form of the battery the galvanic element.

Text: Alexandra Kohlhöfer