My Day at the South Pole

Since December 2025 I‘ve been living and working at the South Pole – the coldest place on Earth. There are a lot of special challenges involved, but it’s a once-in-a-lifetime experience. Sunshine, blue sky, no day/night rhythm, ice and snow, and temperatures constantly at 30° C below zero: that’s the Antarctic in the summer, while it’s winter in Europe.

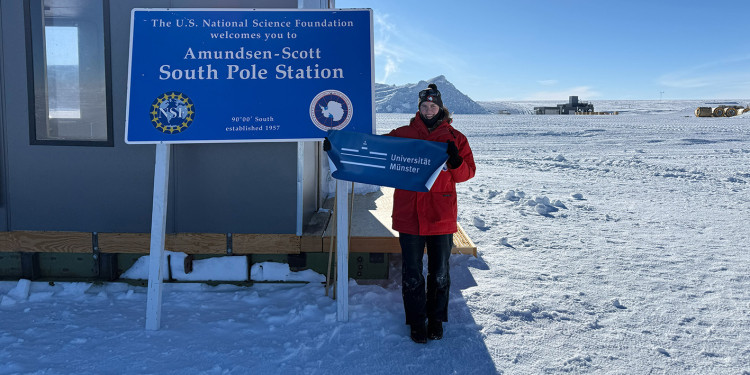

As part of my PhD dissertation at the Institute of Nuclear Physics, I travelled here to the Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station to help with the installation of the IceCube Upgrade. IceCube is a telescope, lying deep inside the ice, which is used to trace neutrinos, which are the smallest uncharged particles. Getting here was quite literally a trip halfway round the world: first we took a chartered flight from Düsseldorf – via Dubai and Sydney – to Christchurch in New Zealand, where we spent a few days on our preparatory training and were given our equipment. An Italian military aeroplane then took us to the McMurdo research and logistics station in the south of the Atlantic, although we were unable to land there because of poor visibility, due to clouds, and we had to turn back when we were halfway there. That day, I spent almost twelve hours sitting in an aeroplane – just to find myself landing back in Christchurch. The second attempt was successful, though. After a three-day interim stop in McMurdo, we flew on for another four hours – and then I finally reached the South Pole.

What does a typical day for me at the South Pole look like? In the first few weeks it began with a walk through the ice and the snow because my accommodation was on the outside area of the station, in a so-called hypertent. These are heated tents with nine rooms. Each room is equipped with a bed, a bedside table and a wardrobe. Being housed in this tent meant that every morning I had to walk about five minutes to the research station to have my breakfast. At the beginning, I always put on very warm clothes: long underwear, thick trousers, thick shoes, a pullover, a fleece jacket, beanie, gloves and of course the “big red” – a red winter jacket which was developed especially for Antarctic conditions and which everyone wears. After I arrived at the station, I had to take almost everything off again. After a while I got used to the temperatures and was able to walk to the station in leggings and sweatpants, a pullover, big red, a beanie and normal sports shoes. Nowadays I don’t take my “breakfast walk” anymore because I was able to move into the station, where most of the people live.

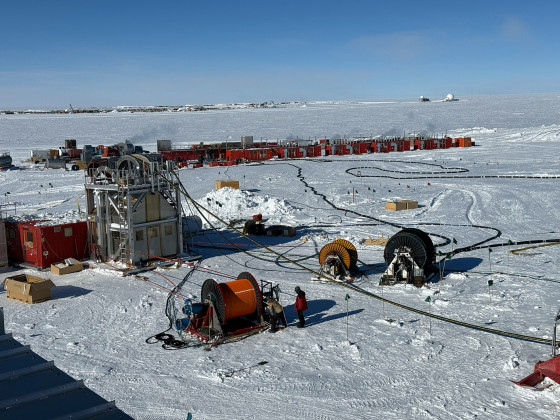

On preparation days we take the optical modules for the neutrino detection to the respective borehole in the so-called drill camp and prepare the mounting process and the connecting cables. The installation site is around ten minutes from the station on foot, and you can walk there via a broad path or by using the snowmobile. On each installation day we install around 110 modules in the boreholes. Each member of the team has their defined task, and it’s a constant battle against the clock. The boreholes have a lifetime of around 50 hours before they freeze up again. This means we have to be finished in time, and that’s why the shifts last up to twelve hours on such days. My task is to document the installation process.

Everyone has days off too, and there’s a lot to do in the station. There is a large selection of books, films and board games. The station even has a small fitness room and a sports hall, and for musicians there’s a music room. I like to watch films with the colleagues from my shift – or we play darts or billiards. My days end with supper – which is breakfast for the day shift.

Editorial note:

The work on the IceCube Upgrade was successfully completed at the end of January, and since shortly after this article was written, Berit Schlüter is back home again.

This article is taken from the university newspaper wissen|leben No. 1, February 4, 2026.

The upgrade of the IceCube Observatory

More than 400 international physicists in the IceCube consortium use the data provided by the observatory at the Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station to do research work on the cosmos with the aid of neutrinos. The huge detector below the surface of the ice has a volume of around one cubic kilometre, and it registers the extremely rare interaction between the neutrinos and the ice. The deepest measuring points are located around two and a half kilometres below the surface of the ice. When the neutrinos interact with the ice, blue light is produced. IceCube captures this light by means of optical sensors (Digital Optical Modules, DOM). The data can be used, for example, to reconstruct which direction a neutrino came from and how much energy it possessed.

The installation of the upgrade was completed at the end of January. The detector now has around 700 new sensors in its central area. This concentration means that neutrinos with even lower energy can be detected. This is particularly interesting for studying so-called neutrino oscillations. In this case, one sort of neutrino transforms itself into another one. Also, with the new technology IceCube reacts more sensitively to low-energy neutrinos from so-called core-collapse supernovae. When a massive star collapses to a neutron star, huge quantities of neutrinos are produced.

The working group led by Prof. Alexander Kappes at the Institute of Nuclear Physics played a leading role in the development of the mechanical design of the so-called multi-PMT Optical Module (mDOM) and characterizing its optical properties. The group was also responsible for the pre-assembly of a component for all 430 mDOMs. The modules have a sensitivity to light which is three and a half times greater than that of the sensors previously used. “What’s special about the IceCube modules,” says Alexander Kappes, “is that they need to be able to withstand extremely high pressures of up to 700 bar at temperatures as low as minus 30 degrees Celsius – and function in an absolutely reliable way. This is because they are no longer accessible after they have been installed.” Engineers from the Institute of Nuclear Physics were also involved in the development of the modules. The Institute’s precision mechanics workshop constructed components for test stand, and the corresponding electronics comes from the electronics workshop.