From a lime to a patent

In mid-October the broadcaster Deutschlandfunk reported: “German research institutes hold a leading position in patent applications”. The basis for this was a study carried out by the European Patents Office (EPO) which showed that around one third of all European patent applications made between 2001 and 2020 came from German institutes. At the University of Münster, too, there are discoveries which lead to patents being granted. Who is involved in the process? What are the obstacles? What follows when a patent is registered?

The legal position

At the beginning of a patenting process is an invention. Paragraph 1 of the German Patents Act states: “Patents are granted for inventions in all fields of technology, provided they are new, are based on inventive activity, and can be applied commercially.” 147 paragraphs then provide detailed regulations for what can be patented. What cannot be patented are, for example, “processes for cloning people”, scientific theories or mathematical methods.

The role of the inventor(s)

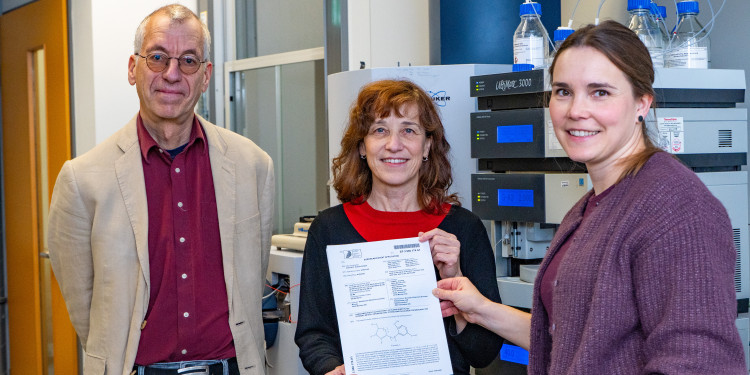

At the University of Münster’s PharmaCampus, in 2019, there was inventive activity, with something new resulting from it which did not correspond to the state-of-the-art technology at the time – and which was therefore, in principle, patentable. Prof. Martina Düfer and her doctoral candidate at the time, Dr. Alexander Hake, from the Institute of Pharmaceutical and Medicinal Chemistry, and Prof. Andreas Hensel and his erstwhile candidate, Dr. Nico Symma, from the Institute of Pharmaceutical Biology and Phytochemistry had come across six new alkaloids from lime blossoms and their effects on the human organism. “Sometimes, chance lends a hand,” says Martina Düfer with a laugh. The alkaloids inhibit the enzyme acetylcholinesterase, and as a result the quantity of active acetylcholine increases. “This neurotransmitter acts as a motor for memory, cognitive stress resistance and mental flexibility,” Andreas Hensel explains. The invention makes it possible, he says, to influence mental and emotional stress.

After the discovery, the team considered the biomedicinal potential and possible synthesis strategies, analysed the market and – as the Employee Inventions Act stipulates – reported the invention to the University Research Department. The 20-page report contains personal and work-related details, as well as a description of the invention and its possible application. The reply to the first question to be answered in the document is so important that it is decisive for the success or failure of the entire project: “What publications or public utterances have you already made on the topic of the invention?” Of the eight possible answers – for example, “dissertation” or “talk given” – only one is correct: “none”. As Katarina Kühn from the Innovation Office (AFO) explains, “Any kind of publication before registration brings the claim for a patent to an end. For this reason, secrecy is essential before any application for a patent is made.” The lime blossom team knew this and acted accordingly.

The role of the University

After a discovery has been made in an institute or a laboratory, the Research Department starts its work – among other things, with its Legal Department and the AFO patents specialists Katarina Kühn and Janita Tönnissen. These two examine the report of the discovery and forward it – as in the case of the lime blossom extract in 2019 – to the PROvendis company. If the invention comes from the field of medicine, the Faculty’s own “Clinic Invent” is responsible. “The patents exploitation agency PROvendis, a subsidiary of 27 universities in North Rhine-Westphalia, evaluates the invention under legal, technological and economic aspects,” Katarina Kühn explains. “It then makes a recommendation to the university as to whether it should lay claim to the invention or release it.” If a claim is to be made, PROvendis commissions a patents law firm.

This is what happened with the lime blossoms. “The patents lawyer drew up the patent specification in less than one week, and our telephone lines were red hot in those few days,” Andreas Hensel recalls. The University accepted the invention, and on 30 October 2024 the European Patents Office granted patent EP3960174. This protects the intellectual property of the inventors in numerous European countries. There were almost five years between the discovery and the granting of the patent – which is not uncommon. “Patience and perseverance are necessary,” says Katarina Kühn. “Also, the inventors have to continually contribute their expertise.” This is what the pharmacy team did. At the same time, the University provided support: in the spring of 2025 the University’s management decided to fund the invention through the validation fund in order to make it marketable. “The University supports inventors financially, both with its own funds and with funds provided by the state of North Rhine-Westphalia, as well as by providing expertise for transferring innovations to society and to business. Successful patent exploitations also benefit the University,” as Katharina Steinberg, Head of the Research Department, points out.

The next steps

For Martina Düfer, Andreas Hensel and their team, however, the substance patent is not the end of their process of invention. With the help of the validation fund and the establishment of a start-up, they aim to put the extract on the market, in the form of a medicine or a dietary supplement. “It’s a complex undertaking. We’re moving out of our laboratory and, instead, are dealing with wholesale prices, production processes and marketing,” says Andreas Hensel. “But working together like this is fun,” Martina Düfer adds. Thanks to their expertise and their perseverance, as well as to the advice provided by the University and by PROvendis, they have already cleared some of the hurdles.

Author: André Bednarz

This article is taken from the university newspaper wissen|leben No. 8, 10 December 2025.

Further information

- Prof. Dr. Martina Düfer at the University of Münster

- Prof. Dr. Andreas Hensel at the University of Münster

- Advice on Intellectual Property from the Innovation Office (AFO)

- Validation fund of the University of Münster

- The December issue of the university newspaper as a PDF file (in German)

- All issues of the university newspaper at a glance