Between fluid identities and the potential for political learning

Interview with Philosopher Franziska Dübgen on her research at the Cluster of Excellence

In her research at the Cluster of Excellence, political philosopher Franziska Dübgen, head of the project “Articulations of the ‘political’ in contemporary postcolonial contexts of north and sub-Saharan Africa”, deals with innovative concepts of the political, her focus here being primarily on concepts that political philosophy and political theory have developed in recent decades in and with regard to Africa. In doing so, she highlights the postcolonial theory and work of scholars whom Western political philosophy in the German-speaking and Anglo-Saxon world has largely ignored or only received marginally. In this interview, she talks about her project at the Cluster of Excellence, the potential for learning between North and South when it comes to dealing with global challenges, and the debate on postcolonialism.

In your project at the Cluster of Excellence, you are studying innovative concepts of the political that political philosophy has developed in recent decades in and with regard to Africa. Which scholars are particularly important for your research and what stance do they take on questions of identity, belonging and politics?

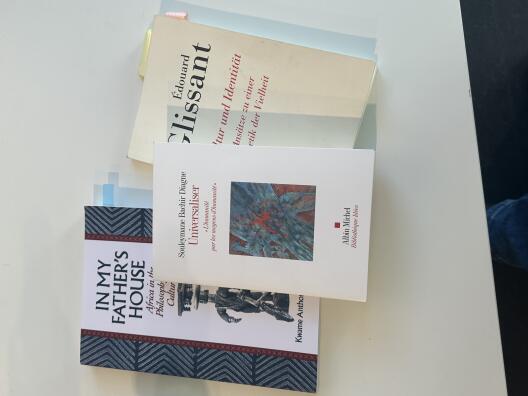

In my research at the Cluster of Excellence, I deal with philosophical positions and scholars who advocate a new humanism and who rethink questions of identity, belonging and political community. My research focuses on non-European, especially African, Political Philosophy – capitalised because I am addressing it as a philosophical discipline – and thus on a philosophy that has developed many of its positions against the backdrop of Africa’s colonial history. The history of European colonialism, past and ongoing racism, and unequal geopolitical and economic power relations – these play an important role in African philosophy at the level of critical analysis and description. Besides this critical diagnosis of the present, I am particularly interested in the normative visions of the future that these scholars present – visions that reconceptualise human coexistence in all its complexity, as well as our coexistence with nature. I am thinking here of scholars such as Souleymane Bachir Diagne, Paulin Hountondji and Édouard Glissant.

Take the work of the Caribbean scholar Glissant, whose writings reflect on the role played by the traumatic crossing of enslaved people from Africa to the so-called New World, i.e. North America. He develops here a new conception of identity as a complex network of roots (rhizome) that constantly forms new branches and can sprout in unexpected places. Even in contexts marked by violence, such as those of enslavement and instances of labour migration under degrading conditions, he argues that the fusion of different linguistic, cultural and everyday practices can yield new forms of identity that enable people to feel at home – despite the traumas they have experienced. For Glissant, identity is therefore not simply a given, but is produced in the diverse forms of human relationships – and changes the community to which we pertain. Anthony Kwame Appiah, who has roots in Ghana but now researches and teaches in the USA, has also written very interestingly on questions of identity and a new cosmopolitanism.

In general, what the scholars I study have in common is on the one hand their criticism of an overly narrow understanding of belonging and identity, one that claims that these are simply given by birth or origin, and on the other their argument that community can take many different forms – and that a political community should take this diversity into account. These positions lead us to question our traditional ideas of a nation that is as homogeneous, i.e. uniform, as possible. And they are directed against the nationalism, identitarian narrow-mindedness and ethnocentrism that we have recently witnessed here in Europe, but also in many other parts of the world.

The question of methodology arises not only for research in the natural and social sciences, but also for work in the humanities. What methods do you use in your research and what challenges do you face?

When reading texts from other linguistic and cultural areas, it is important to reflect on questions of transcultural translation, i.e. the translation of meanings across cultural and geopolitical boundaries. The hermeneutic perspective from which I read the texts of African writers here in Europe is shaped by a specific historicity, certain cultural assumptions, and other living and reading experiences. I must be aware of this distance between myself and the writers I am studying in order to find ways and means of dealing with it and achieving an appropriate understanding of the text. Contextual knowledge, familiarity with the complex history of African philosophy, which has been struggling with its subject matter and appropriate methods since its academisation in the 1960s, and active dialogue with philosophers from north and sub-Saharan Africa help me carry out this interpretive work.

It often becomes apparent that our reference systems both overlap in some respects due to the education system shaped by the former colonial powers – France, for example – and also differ greatly. In both cases, it is important to consider which positions in the history of philosophy are being referred to. In the Arab-Islamic philosophy of North Africa, an important point of contention is how to approach the relationship between theology and philosophy. This then also has implications for the role that religion is accorded in a political community, for example with regard to the question of whether radical secularism (France is often cited here) is appropriate for these societies. In sub-Saharan philosophy, on the other hand, there is a discussion about the role that should be played by orally transmitted knowledge, African local languages and pre-colonial practices of coexistence in legitimising political systems – and what status we should accord to so-called ethnophilosophy, which emerged within anthropological research on Africa.

If such knowledge resources are considered to be of great importance in the ongoing process of decolonisation, then traditional (and thus reconfigured) forms of decision-making come to the fore, such as so-called palaver or consensus democracy, which claims that what is central are the principles of inclusive dialogue with all affected groups, orientation towards the common good, and consensus-based decision-making. However, there are of course also conservative, hierarchical and exclusionary practices from the past that need to be overcome today and are therefore the object of criticism.

Now to the keywords ‘postcolonialism’ and ‘decoloniality’: What does postcolonialism mean, what is the state of research, and what is the difference between postcolonial and decolonial theory?

At the heart of the postcolonial debate, which became particularly heated in academic circles around the beginning of the 1980s, is the critical analysis of the continuing impact today of colonial structures at a political, material and epistemological level. ‘Postcolonial’ therefore does not mean that colonialism is over and a relic of the past, but rather that its effects are still felt today. ‘Postcolonial’ and ‘decolonial’ theory agree on this point. Major differences emerge, though, when it comes to the question of how the spheres of politics, economics and knowledge can be ‘decolonised’. While ‘postcolonial’ theory, which is my primary focus, uses theoretical tools from the European philosophical tradition (such as poststructuralism, psychoanalysis and Marxism), ‘decolonial’ theory advocates a break with this European heritage – and also a break with the philosophical Enlightenment. Instead, decolonial theory increasingly turns to local knowledge resources from the Global South and provides alternative scripts for emancipation.

As far as the state of the postcolonial debate is concerned, this has unfortunately been reduced in feature articles and public perception to a supposed anti-universalism and identity politics in recent years. While these positions do exist, they do not dominate academic debate. Rather, the scholarly debate concerning postcolonial theory is extremely complex and contains very different positions on key issues that are fiercely contested, such as questions of the genesis and validity of human rights, gender equality, the relationship between individual and community, and the justification of a universalist ethic. There are, for example, scholars such as Makau wa Mutua who argue that interventions based on human rights are patronising and instances of geopolitical instrumentalisation. At the same time, however, thinkers such as Hountondji and Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak defend human rights as a transcultural achievement with an important liberating potential.

Recent decades have seen a significant increase in criticism of Eurocentric positions, i.e. the purely academic and political focus on Western or Western European experiences, knowledge and values in dealing with global challenges. How far can positions from African philosophy act as a necessary corrective here?

If we really want to create transnational institutions and structures that can tackle current global challenges such as climate change and military conflicts, then we need a greater diversity of voices and genuine participation from actors from different regions of the world. This has long been necessary for reasons of procedural justice and fairness, but a transcultural approach also promises epistemological advantages: the different horizons of experience and intellectual genealogies expand the reservoir of knowledge that we can draw on in our search for constructive solutions to global problems. For my research, this means that I assume that we in Europe can learn from African philosophy. Political Philosophy there must, for example, take as its starting-point for how it conceives future politics societies that are extremely heterogeneous in terms of religion, culture or language. Today’s nation states in Africa are a product of arbitrary border demarcations and a legacy of imposed state bureaucracies. Our societies here in Europe also face the challenge of dealing with diversity in a constructive and positive manner. Also, there is also a need here for increased engagement and identification with political institutions on the part of the population. The challenges therefore overlap to a certain extent.

What specific political measures and demands for reform could current postcolonial or African positions be translated into and implemented?

First of all, we must acknowledge the crimes and injustices of the past. Issues such as restitution, the search for truth, land distribution and reconciliation continue to be important issues in ethical and political debates in Africa. In South Africa, for example, a recurring theme is the issue that persists even after the end of apartheid of the unequal distribution of land and economic resources. In terms of education policy, students at many universities have demonstrated in recent years for teaching to be more closely aligned with their local social realities and to convey a plurality of forms of knowledge – including African, endogenous knowledge production. Other urgent issues that need to be addressed are questions of how to treat nature appropriately, freedom of movement between continents (keywords: migration and exile), and fair international trade conditions.

What fascinates you personally about your research?

On the one hand, I am fascinated by the capacity, despite and because of the experience of suffering and oppression, to formulate perspectives that hold fast to humanity, love and justice. I am also inspired by the beauty, poetry and wisdom of African and Maghreb cultures – without wanting to idealise them. Not least, the philosophies that emerge there mirror my own existence: in terms both of what unites us and of how different we can be. (tec/pie)