(In)visibility. Or: visualizing and perceiving an invisible threat

Dossier “Epidemics. Perspectives from cultural studies”

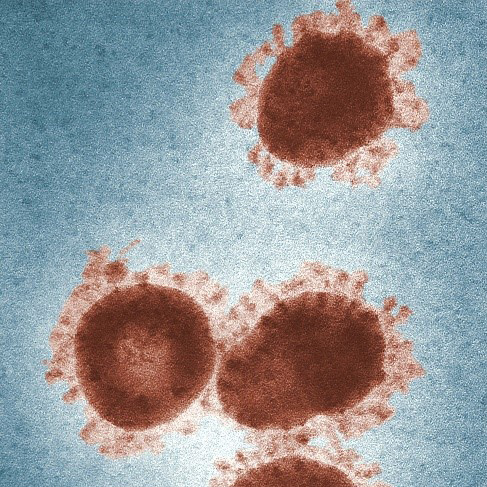

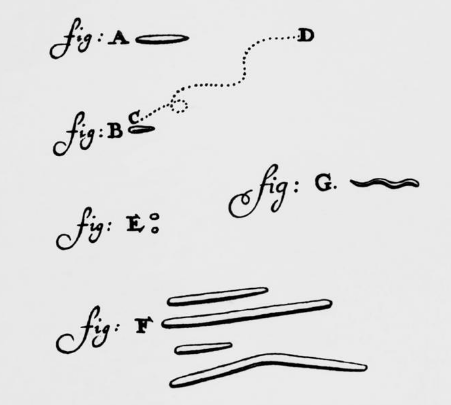

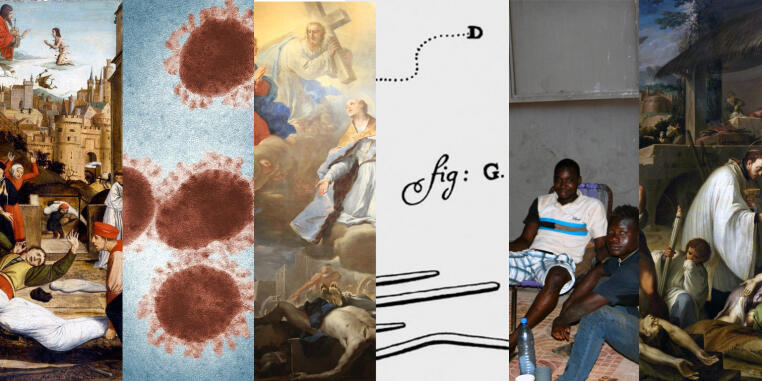

It is invisible. At 80-160 nanometres, the corona virus is a challenge even for state-of-the-art imaging technology. The urge to make the invisible and how it works visible, to give it a shape, has accompanied humankind ever since epidemics began threatening our living space. The invisible, which cannot be smelled, tasted or touched, is deeply unsettling. It was not until the work of the bacteriologist Robert Koch (1843-1910) that pathogens became visible. The images provided by science generate comprehensibility, credibility; they give the impression of mastery over the invisible. The global spread of the corona virus turns us into consumers of spatial data analysis and location intelligence tools; interactive maps and charts break down the complexity of the virus and its consequences. And yet there is still great uncertainty, since the imperceptibility of the virus reinforces an atmosphere of social threat and mistrust. War metaphors are used to declare war on the invisible enemy.

In this chapter, the “Perspectives from cultural studies” are devoted to the question of how the invisible virus, the invisibility of epidemics, has been made visible, graspable, tangible, and legible over the centuries, and how the perception of the invisible threat has influenced societies.