Tiny beings

By Martina Wagner-Egelhaaf

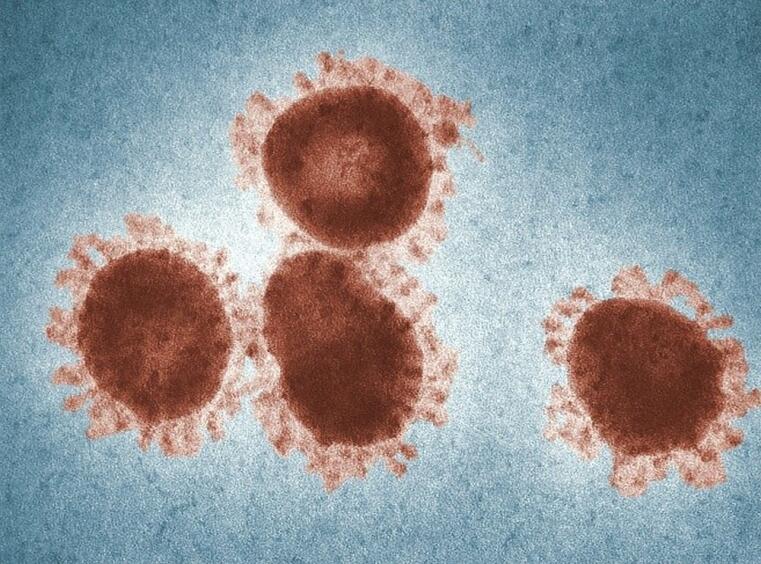

Unless we work in an institute of virology, none of us has ever seen a corona virus. Nevertheless, since the beginning of the pandemic, it has been visible as a pictorial model across the media, in the form of a differently coloured and somehow unpleasant spiky sphere. At the same time, we now have the impression since learning to live with corona that the media presence of this spherical being has diminished somewhat, and given way to flatter, and yet more vivid, representations.

Literature also makes the invisible visible. Olga Tokarczuk, the Polish Nobel Prize winner of 2018, published a novel with the baroque title The Books of Jacob, or A great journey across seven borders, through five languages and three major religions, not counting the minor ones. A journey told by the dead and supplemented by the author using the method of conjecture, drawn from various books and enriched by the imagination, the greatest natural gift of the human. To the wise for memory, to the countryfolk for reflection, to the laity for edification, to the melancholic for diversion. The novel tells in a fictionalized form of the life of the cabalist and founder of Frankism, Jacob Joseph Frank (1726-1791), who converted from Judaism to Islam and then to Christianity. When the protagonist and his followers arrive in Mielnice, Galicia, in 1755, a plague has broken out there:

Polish guards are standing in the village; because of the epidemic, they do not want to let any travellers from Turkey pass through ...

The tavern seems well supplied, but the proprietor explains that the plague is driving people away; nobody dares to go out and buy from those whom it has infected. What they had in their own supplies is used up; they want to condone him and provide for their own food. When he speaks, he keeps away from them, keeps a safe distance, he fears their breath and their touch.

That unusually mild December has brought to life tiny beings that at this time of year usually slumber deep in the frost-hardened earth, but have now crawled to the surface for warmth, to bring doom and to kill. The tiny beings hide in the formless, thick fog, in the stuffy, poisonous vapour that hangs over the villages and towns, in the foul-smelling breath that the bodies of the afflicted exhale – in everything that people call ‘pestilential air’. If this air enters the lungs, the tiny beings immediately enter the blood, inflame it, penetrate the heart – and the person persishes (Olga Tokarczuk, The Books of Jacob, 857-858; my translation).

Some of this is familiar: border controls, empty restaurants, concern for essentials, distance from others. We do not find out which epidemic Tokarczuk’s novel deals with, but the pathogens are portrayed as “tiny beings” that rise from the ground. In the German translation of the Polish novel, the word Wesen is used for “beings”, a word that, according to the German dictionary (Duden), only exists in German and Dutch. The meaning of Wesen alternates between ‘existence’, ‘higher being’, ‘living being’, ‘object’, and ‘true nature’; as in Tokarczuk’s story, the word has an active connotation. Now, a virus is not a living being, but a bacterium is a living being. Both are tiny and invisible to the naked eye. Fog and vapour (smoke) are also media of invisibility, since they themselves are visible, while at the same time denying visibility. Indeed, when the tiny beings rise up in the fog and vapour, their invisibility becomes vividly visible.