TIME, or: After the crisis is before the crisis

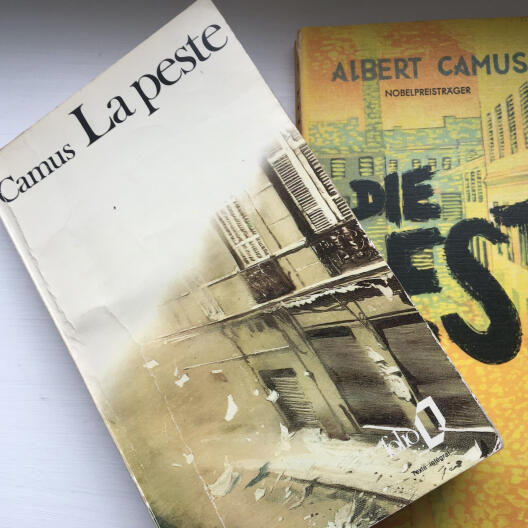

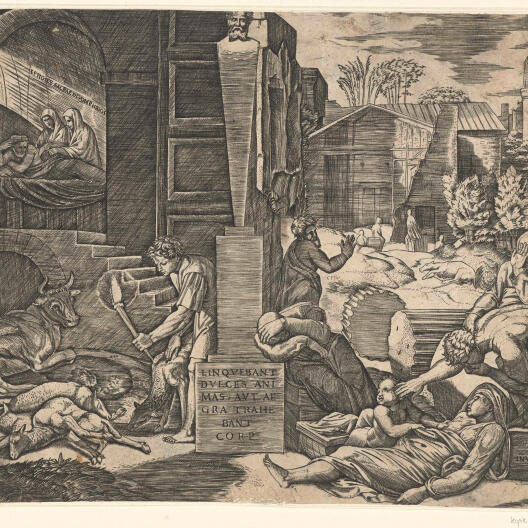

Dossier "Epidemics. Perspectives from cultural studies"

The coronavirus has confused our relationship to time. Before, everything ran like clockwork – only a little too fast perhaps, so we had the constant feeling that we had to run simply to keep up. The lockdown has relieved our schedules somewhat, but has not necessarily given us more time. Digital learning, home schooling, following protective guidelines – all this ‘costs’ time. As Marie Schmidt wrote in the Süddeutsche Zeitung on 16 April 2020, the pandemic has “both glaringly decelerated and accelerated time”. Nothing will be quite the same, some say; or, as the ever pessimistic writer Michel Houellebecq told us in the Frankfurter Allgemeine on 10 May 2020, everything will remain exactly the same, only become worse. The following articles, written from the perspective of cultural studies, provide further thoughts on the relationship between epidemics and time.