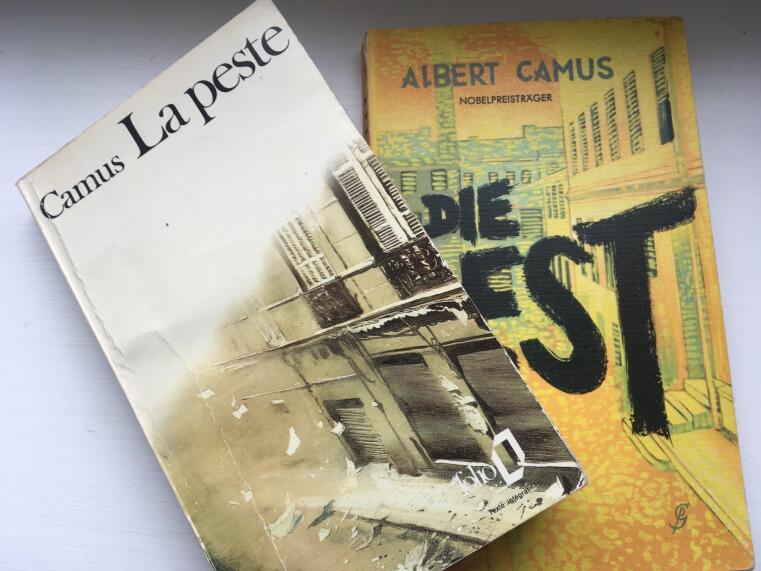

Classic redivivus: Albert Camus, The Plague (1947)

By literary scholar Martina Wagner-Egelhaaf (German studies)

Published in 1947, Albert Camus’ classic novel The Plague has gained renewed relevance in recent weeks and months. According to media reports, sales figures have risen significantly in France and Italy, but also in Germany. An inquiry with a Münster bookshop revealed that the book had often been unavailable for a few days because it had had to be reprinted. Stocks at wholesaler Libri show that Camus’ novel is currently on a par with the bestsellers. People are obviously looking for a reflection of their own situation in literature, which is something that also seems to be indicated by Daniel Defoe’s motto that precedes the text: “It is as reasonable to represent one kind of imprisonment by another, as it is to represent anything that really exists by that which exists not!” (Albert Camus, The Plague, translated by Stuart Gilbert, London: Penguin, 1960, 3).

The novel’s opening sentence is: “The unusual events described in this chronicle occurred in 194-, at Oran” (5). The text is designed specifically as a chronicle, although the events depicted are fictional. The incomplete date, suggesting a ciphered documentary reference to reality, also refers to the unreality of what is depicted. The novel is interspersed with temporal references, and these are intended on the one hand to help record the events of the crisis, while on the other pointing to the sheer impossibility of comprehending them. Here are just a few examples: “On his [Rieux’s] way out at five” (13), “Next morning – it was 18 April” (14), “From now on it can be said that plague was the concern of all of us” (57), “It was a period of sheer lethargy” (92), “All Souls’ Day that year was very different from what it had been in former years” (192), etc. Forced separation particularly affects the sense of time that lovers have: “Whereas during those months of separation time had never gone quickly enough for their liking and they were always wanting to speed its flight; now that they were in sight of the town they would have liked to slow it down and to hold each moment in suspense once the brakes went on and the train was entering the station. For the sensation, confused perhaps but none the less poignant for that, of all those days and weeks and months of life lost to their love made them vaguely feel they were entitled to some compensation; this present hour of joy should run at half the speed of those long hours of waiting” (239-240).

The story begins in April and the gates of the city are opened again in February. And there it says: “In the forts, on the hills, under a sky of pure, unwavering blue, guns were thundering, without a break. And everyone was out and about to celebrate those crowded moments when the time of ordeal ended and the time of forgetting had not yet begun” (241). And, as if to disturb the chronology of the report, a mild autumn breeze suddenly blows at the end of the novel. For the main character, the doctor Rieux, who at the end reveals himself to be the author of the chronicle, the flow of time has in any case changed into a consciousness of temporal latency, for he knows “that the plague bacillus never dies or disappears for good; that it can lie dormant for years and years in furniture and linen-chests; … and that perhaps the day would come when … it roused up its rats again and sent them forth to die in a happy city” (252).

Incidentally, Defoe’s motto quoted at the beginning of the book also refers to the allegorical character of the novel, with the epidemic of the plague also representing the Nazi occupation.