The plague as a transitory moment: Raphael and Raimondi

By art historian Eva-Bettina Krems

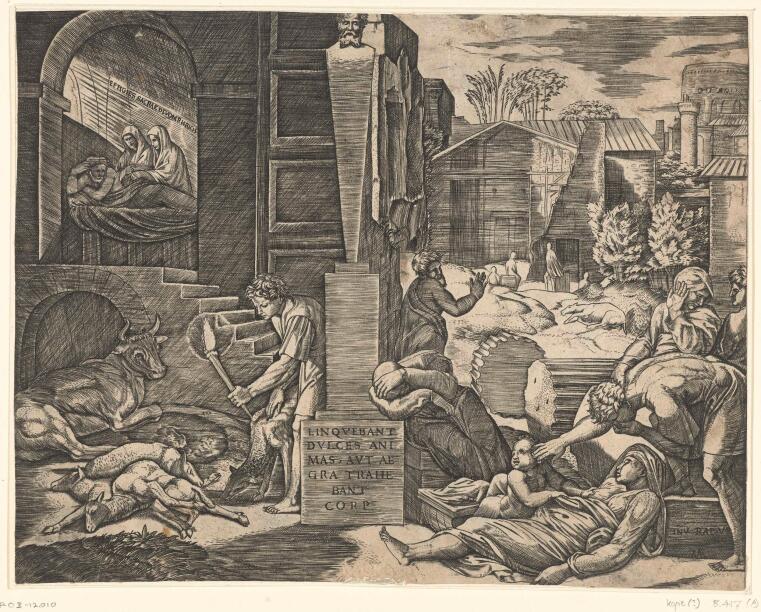

500 years ago, on 6 April 1520, the famous Renaissance artist Raphael died at the age of just 37. To mark this anniversary, many museums around the world planned to put on exhibitions, with these now having to be closed or postponed due to the corona crisis. There has been much speculation about the reasons for Raphael’s early death: repeatedly cited as causes are malaria or syphilis, but also the plague. The threat of epidemics such as the plague was part of everyday life in the early 16th century, as it was generally in the early modern period. In 1515, five years before his death, Raphael turned to this theme, too. His drawing became famous through this copperplate engraving by Marcantonio Raimondi. In it, Raphael does not present the awful event as something that happens in contemporary Rome, but rather clothes it in his usual antique mythical garb. However, this by no means diminishes the force of the depiction; rather, the very fact that the event is timeless greatly increases its effect. Its disturbing relevance today is confirmed by the pictures from Italy in March 2020 that are burnt into our collective memory.

The protagonists of Raphael’s portrayal are the mythical founding father of Rome, Aeneas, and his companions, and Raimondi’s engraving adds to the portrayal literal quotations from the text source (from: Virgil, Aeneid, Book III, 138-140). Aeneas did not know for a long time exactly where he was to found the new city after his escape from burning Troy. Due to a misinterpretation of the Oracle, he and his entourage landed during their long odyssey on the island of Crete, which they then considered their new home. Aeneas immediately built a wall around the city, while his companions tilled the fields and built houses. There is hardly anything left to be seen on the engraving of these civilizing measures testifying to a new beginning and hope, because fate had determined otherwise: “suddenly from a polluted quarter of the sky there came a cruel, suppurating plague upon our bodies and upon the trees and crops” (Aeneid, Book III, 138-139). A plague suddenly destroyed everything that they had laboriously built. Virgil sums up this moment as a fundamental break in time and as destructive of the future in a few succinct lines, culminating in the words: “Men were losing the lives they loved or dragging around their sickly bodies” (Aeneid, Book III, 140).

Thus, the most disturbing scene in Raphael’s depiction is also the one closest to the viewer: in the bottom right-hand corner, a man, holding his nose to protect himself from stench and infection, tries to stop an infant from drinking from the breast of his mother, who has died of the plague. Behind him, a woman puts her hand on his shoulder to prevent him from coming too close to the dead woman, who is placed on the ground in a cruelly similar way to the sheep carcasses illuminated by a torch on the left of the depiction.

The engraving is divided by a monumental herma in the centre, at the base of which is the broken figure of a woman in mourning. The herma can be interpreted as the God Terminus, as the border between life and death: the ruins scattered on the ground correspond to this depressing concept of human beings and animals dying of the plague. But, divided deliberately into a dark and a light side, the depiction also offers a counter-concept to the suddenly lost future and hope for a peaceful life, one that unfolds its depths with a narrative time structure: in the top left-hand corner, Aeneas is awakened in his moonlit bedroom by the domestic gods of the Phrygians, who advise him to leave Crete quickly to escape the plague. They show him the way to Italy where, according to myth, he was to become the founding father of Rome. Following the direction of escape, and towards the light, there are in the top left-hand corner abbreviations of the Colosseum and the Cestius pyramid, marking the hero’s destination. Aeneas is thus able to escape from the cruel death, the raging plague, which Raphael impressively stages here in a field of tension of continuing relevance between dark and light, between death and life, between suffering and hope.