Masks: Protection or imposition

Epidemics. Perspectives from cultural studies

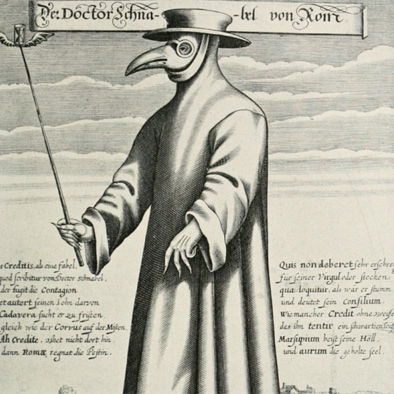

After the initial irritations, we have become more or less used to wearing protective masks in public places. Nevertheless, the obligation to do so seems to have remained a stumbling block that has attracted extreme emotional reactions, for example in demonstrations against state measures aimed at combatting corona. Masks are anchored in culture in many ways. For example, they were worn by the actors in the theatre of ancient Greece, so that the figure depicted could be clearly seen even by distant spectators. In many cultures, masks play a central role in cult and ritual, where they offer people the chance to transform themselves temporarily. Masks are worn in carnivals, where they conceal identities and allow people to playfully accept a different identity. And, finally, the wearing of masks is associated with the criminal milieu; for example, the classic bank robber in films wears a mask that is of course black!

The image of medical staff wearing protective masks in the operating theatre may also have negative connotations when one thinks of serious illness. And yet such masks stand for hygiene, medical standards, and protecting the patient. Is the rejection of everyday masks so great because they constantly remind us of sickness and death? Or is it the restriction of freedom associated with the obligation to wear masks that causes such contrary reactions? However, there is also certainly a creative and humorous use of the everyday mask in terms of the colours and forms that it can have. The following articles examine mask wearing from different disciplinary perspectives, and show that the present obligation to wear a mask is embedded in a cultural context that is consciously or unconsciously part of the debate.