Miasmas, particles, tinder, plague worms, and “levende diertjens”. On how microbes have been made visible for humans

By Historian Katharina Wolff

To begin with a popular epistemological joke: If a tree falls in the forest and nobody sees it, does the tree fall at all?

As a being that is dependent on sensory impressions when it comes to perceiving its environment, the human also has a need, and especially so in times of crisis, to perceive events sensually. Infectious diseases elude this need to a particular degree: the question of what the mysterious entity that seems to be at work there is doing becomes apparent through the symptoms of those who are ill, but the question of what this entity is does not.

Infectious diseases and their pathogens are silent, odourless to the human nose (but not to other noses; corona sniffer dogs are now being trained), without taste in the small quantities required for infection, and invisible. “Where were the microbes before Pasteur?” is the provocative question posed by the sociologist of science Bruno Latour. “They did not exist before he came along” is his immediate answer. In the millennia preceding Robert Koch, there was a great diversity of theories as to what caused a disease.

The idea that there could be – indeed, had to be – “something” invisible yet active has long existed in medicine. In the Hippocratic writings collected between the 6th century BC and the 2nd century AD, there is talk of miasma. Applied to medicine, the Greek term μίασμα (= defilement, contamination) assumed that there were putrid and invisible vapours that caused disease and that arose in certain environmental conditions: the plague was transmitted by especially unfavourable planetary constellations and unpleasantly humid and warm winds, by places that stank such as cemeteries, battlefields, and butcheries, and also by the sick. The miasma theory remained one of the most important explanatory models and bases for action in the defence against epidemic diseases until the 19th century. The work on agriculture of the Roman writer Marcus Terrentius Varro (116 BC-27 AD), Rerum rusticarum, already warned in the 1st century BC that houses should not be built near waters, since the soil there contains “animalia quaedam minuta, quae non possunt oculis consequi”, i.e. animals so small that they could not be seen with the naked eye, but which could penetrate the human body and cause diseases. Much later, one of the most important figures in pre-modern medicine, the Persian physician Avicenna (980-1037), added a chapter on pestilential fevers to his Canon medicinae, describing in it “bad bodies” that bring people disease: “And so the water spoils not because of its composition, but because of what is added to it by bad bodies in the earth that mix with it”. Avicenna’s pathogens were lifeless entities, because the Arabic “أجسام أرضیة خبیثة” (“aǧsām arḍiyya ḫabīṯa”), “corrupted earth-bodies”, means something inanimate such as small particles, but not organisms. His work was one of the most important foundations of university medicine throughout the Middle Ages, and yet the notion of small particles that bring disease was largely ignored.

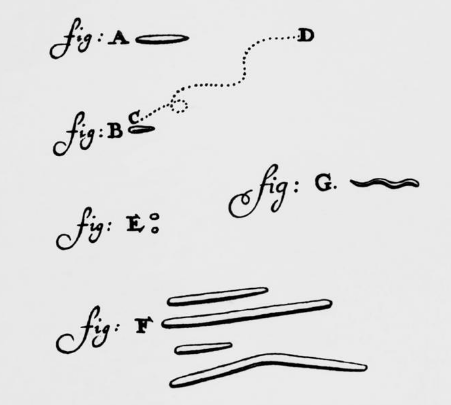

Much later, in the 16th century, the Veronese physician Girolamo Fracastoro (c. 1477-1553) established a new theory of infection. In his major medical work De contagione et contagiosis morbis et eorum curatione, published in 1546, he outlined his theory of the nature of an infectious agent and listed three ways that people could become infected: 1. by direct contact with a sick person, 2. through contact with surfaces that Fracastoro called “fomes”, i.e. “explosive" or “tinder”, and 3. across distances. Fracastoro’s theories did not change the view of European medicine, since they could not be connected to the paradigms of the time. The Thuringian Jesuit and natural scientist Athanasius Kircher (1602-1680) also tested new methods. Using early microscopes and numerous experimental designs, he attempted to provide evidence of the smallest life forms. Using a chemical decomposition experiment sometimes with meat and sometimes with the blood of those ill with plague, he searched for tiny organisms invisible to the human eye alone. He found them, he thought – and he described in microscopy so-called “plague worms” in the blood of those ill with plague, these “worms” being, he thought, the cause of the plague. But Kircher’s findings also had no effect in the context of the dominant theories of the time (miasma theory and humorism). Soon the Dutch merchant and land surveyor Antoni van Leeuwenhoek (1632-1723) used a secret process to manufacture numerous microscopes (presumably, he melted his lenses from liquid glass instead of grinding them). He microscoped a variety of objects, including his own saliva, and what he saw in them was bacteria, which he drew and communicated to the Royal Society. He called the structures that he had found “levende diertjens”, i.e. “living animals”. Thus, the microcosm slipped from invisibility into the light of the visible world.

The founders of new sciences such as microbiology and hygiene, chemists and physicians such as Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch, deduced something new from their observations, formed their own theories, and finally solved numerous ancient mysteries regarding the encounter between human and microbe. Laboratory diagnostics today serve the conditions of human perception described at the beginning of this piece: these are makeshift constructions that enable us to make an invisible thing perceptible. Thus, all test systems end up in observations and measurements that show the human sensory organs the presence of a sought-after pathogen, e.g. in microscopy, fluorescence microscopy, in Gram staining, on growth media, and in immunoassays such as the ELISA test. Measuring devices with finer sensors than humans translate their values into interpretable results.

The coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 is so small that it can no longer be seen with the optical microscope. The omnipresence of the corona sphere is therefore a result of the human need that is still present even in the era of microbiology to gain an idea of the “enemy”: a sphere studded with spikes with little balls at the ends. Illustrating and making the virus visible do not provide laypersons with any insights; there are no deducible consequences for the observer. Making this virus visible is due to the need for understanding, for comprehension, to the desire to obtain an idea – but it misses the mark. For, what do we learn from it? As they see, they see nothing. Or, to return to the joke mentioned at the beginning: the tree falls, and no one sees it fall – but everyone lives with the noticeable tremors that this event brings with it. Epidemics thus remain mysterious events even in the 21st century, in the age of microbiology – their effects are clearly perceptible, but their causes remain invisible in everyday life.