“... aiuti celesti e humani”: multiple measures to combat the plague in Rome in 1656/57

By art historian Eva-Bettina Krems

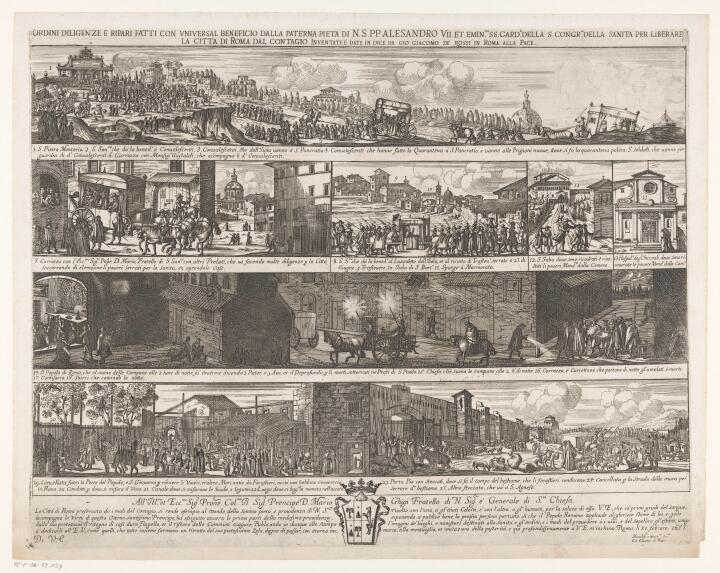

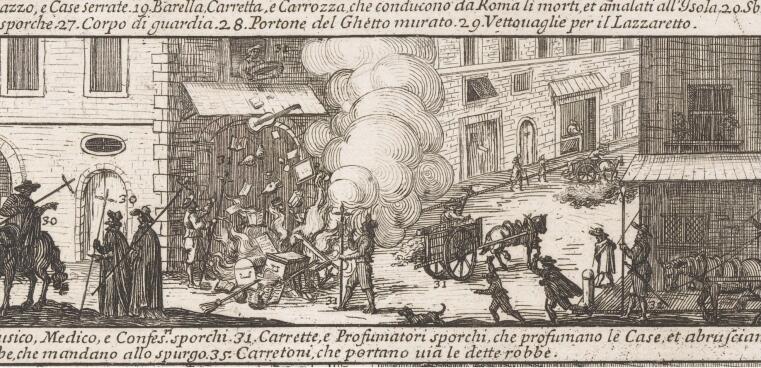

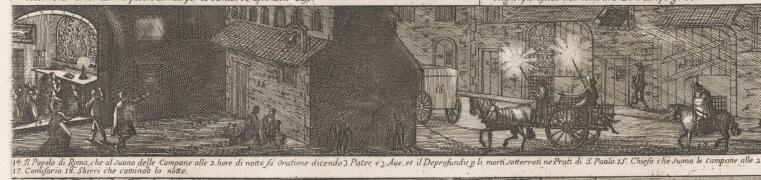

Fig. 1-3: Louis Rouhier (copper engraver)

The plague broke out in Rome in the spring of 1656. The epidemic had spread from North Africa to Spain and southern France in the mid-17th century, and had already reached Sardinia (then part of the Kingdom of Spain) in 1652. Despite the trade barriers against Sardinia, the plague ravaged Naples four years later, in 1656, where it killed an estimated 100,000 people, about a third of the entire population. Rome was dependent on grain supplies from Naples, and so the authorities immediately began in spring 1656 to patrol the border and carefully inspect all arriving ships for sick crew members and travellers. Despite these precautions, several people fell ill in Trastevere in May. Today, this Roman district on the other side of the Tiber is particularly popular with tourists; back then, it was a run-down slum with catastrophic conditions where the plague had a field day. Within a few days, new cases had also appeared in the adjacent Jewish ghetto as well as in many other parts of the city.

Despite the problematic conditions, especially in the poor quarters, the city, which according to the Easter census of 1656 had about 120,000 inhabitants, suffered only about 10,000 deaths that were directly attributable to the plague, and the plague was declared vanquished in August 1657. This mortality rate is only about half that of Naples, for example, or London nine years later, where 80,000 people died of the plague out of a total population of 500,000. The Rome mortality rate has probably been set too low; nevertheless, despite all the drama of the absolute figures, the Holy City got off reasonably lightly. What is interesting about this epidemic in Rome in 1656/57 is not so much the actual measures taken (and they were swift, rigorous, and apparently successful). These barely differed from those that had already been gradually developed and refined into a veritable catalogue of measures in Italy, a country that had repeatedly undergone phases of the plague since the Great Plague in the mid-14th century: lazarettos were created, and all infected persons were admitted there (by force if necessary). City gates were locked. No one from countries infected with the plague was allowed into the city. Doctors wore goggles, gloves and masks. Houses and entire neighbourhoods were quarantined. All objects that had come into contact with infected people were disinfected (with vinegar and fumigations). These are just a few of the multiple precautions taken to contain the epidemic.

What is more interesting is that religious life was also severely restricted on the part of the pope: holy masses, processions, pious gatherings, and other church celebrations as well as street preaching were forbidden. But private forms of devotion were strongly encouraged: at the sound of the great bells, people were to recite in private certain prayers and the De profundis for the plague dead, whereby indulgences were granted. For, masses for the dead intended for this purpose, which were so important for the salvation of souls, were also forbidden in the Roman churches. Instead, the pope celebrated numerous masses for the dead, masses that excluded lay people.

Quite unusually, Pope Alexander VII was a powerful protagonist in these measures, choosing to face the looming threat with a different strategy to many of his predecessors, who had immediately fled to their country residences or taken refuge in the innermost chambers of the apostolic palace. In contrast, Pope Alexander VII, who had only been in office for a year, remained in Rome and acted as a responsible sovereign who not only sought to call on divine help by means of religious rituals, but also vehemently pursued extremely modern health measures with the support of the newly created Congregazione di Sanità (Congregation for Health).

Particularly interesting also is the medial documentation of these measures: indeed, the plague in Rome in 1656/57 is one of the best documented epidemics of the early modern period. Not only does the now famous engraving of the “Plague Doctor” date from this year (reproduced by Paul Fürst in his copperplate engraving “Plague Doctor of Rome: Attire to protect against death in Rome. Anno 1656”, supplemented by a satirical poem). There are also numerous pictorial and textual publications about the precautions and measures taken, not a few of which were also initiated and steered by the sovereign, Pope Alexander VII. Hardly any of the numerous contemporary texts are without panegyric hymns to the great achievements of the new pope in the fight against the plague, and these hymns can be attributed to his political commitment to burnishing his own image: for the purposes of marketing, Alexander VII also had his actions depicted in engravings and medals.

Probably unique in this context is a series of three copperplate engravings measuring approximately 40 x 50 cm belonging to the “Ordini diligenze e ripari” by Louis Rouhier, which was published by the successful printer and publisher Giovanni Giacomo de’ Rossi in 1657 and became famous throughout Europe – as a pictorial catalogue of measures in epidemic crises (Figs. 1-3). In four or five pictorial strips one above the other, readable as in a comic strip from top to bottom, it presents the measures of the Congregation for Health appointed by the pope, which consisted of eight cardinals (including the pope’s brother, Mario Chigi) and 28 commissioners, two for each district, each with a precisely defined task.

As the illustrations show, measures to contain the infection ranged from overseeing the cleansing of houses and household objects (Fig. 4), to protecting the non-infected and those in quarantine, to supplying goods and caring for the sick and their families – without neglecting the maintenance of public order by force if necessary and the removal of corpses by wagon and boat. Below the individual pictorial strips are explanatory texts with numbers assigned to the individual actors, actions and buildings.

The engravings themselves are dedicated to the pope’s brother, Cardinal Mario Chigi, to honour his special services as a member of the Congregation for Health. The engravings, especially the second and third of the series, are clearly dominated by the meticulously described health policy measures. However, the inscription on the first engraving states unmistakably that the decisive, even salvific, figure was Pope Alexander VII himself: all precautions and protective measures had been taken “CON UNIVERSAL BENEFICIO DALLA PATERNA PIETA DI NS PP ALESANDRO VII” and the cardinals of the Congregation for Health (whom he had appointed), “PER LIBERARE LA CITTA DI ROMA DAL CONTAGIO”. The paternal mercy of “our” pope, it is said, led to the city’s liberation from the plague. Alexander VII himself is thus the protagonist of the series: in the first and largest strip of the first engraving (Fig. 5), he is shown being carried in a litter on the Gianicolo hill above the plague-stricken district of Trastevere, blessing the numerous convalescents streaming to him. Here, at the beginning of the series, the miraculous result of the precautions and measures is staged in reverse order, as it were, with large crowds of convalescents sinking to their knees to receive the papal blessing.

The pope can be seen again in the pictorial strip below (Fig. 6), this time seated in a sedia gestatoria borne by horses, accompanied by numerous soldiers: here, as the text explains, he blesses the lazaretto on Tiber Island as well as the district of Trastevere, which since 23 June 1656 had been sealed off with a wall and guarded by soldiers.

The strip below (Fig. 7) provides a vivid depiction of nocturnal activities: on the left, nightly prayers in a private room while the bells ring; on the right, the dead are taken away under the supervision of a mounted inspector. This combination of hygienic and police measures with “traditional” religious incantations condenses the overall concept in the fight against the plague, as the dedication on the lower section of the first engraving notes: here the “aiuti celesti ... e ... humani” are mentioned, heavenly and human help combining to help save. This multiple health strategy seems even from today’s perspective extremely appropriate for a city that was economically dependent mainly on the large streams of pilgrims: in normal times, up to a million pilgrims per year came to the Holy City. In retrospect, we gain the impression that the plague had hardly any negative effects on the economic prosperity of the city in the medium term, but was in fact the decisive stimulus: shortly after the epidemic had subsided, Pope Alexander VII was able in his pontificate to develop the Holy City to new heights, making it one of the Baroque era’s most modern and splendid cities.