Ginger (Zingiber officinale ROSCOE)

An antiemetic, carminative and antiphlogistic pungent drug with worldwide distribution and medicinal plant of the year 2026.

by Tobias Niedenthal

Botany

Ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe) is a perennial herbaceous plant from the ginger family (Zingiberaceae). The plant reaches heights of over one metre and has linear-lanceolate leaves over 20 cm long, whose tubular leaf sheaths form a pseudostem. The underground, horizontally growing, branched rhizome serves as a survival organ and is yellowish in colour on the inside [Wichtl 2016].

The wild form of the plant is unknown. Ginger has been cultivated in South Asia for centuries and is now grown in numerous tropical countries, where different chemotypes have developed. Annual global production is approximately 5 million tonnes. India, Nigeria and China are among the main producers. Jamaican ginger, Australian ginger and Bengal ginger are considered to be of particularly high quality [Hook 2025].

History

Ginger was already established as an imported commodity in Greek and Latin specialist literature during the imperial period. Around 70 AD, Dioscorides described the drug as warming, digestive, mildly laxative and stomach-strengthening. It was also said to counteract darkening of the pupil and serve as an additive in antidotes. Celsus lists ginger as an ingredient in Mithridatium, Scribonius Largus in a theriac. Galen classified ginger in humoral pathology and classified it as a warm medicine whose effect, unlike pepper, was slower to take effect but lasted longer [Mersi 2011].

In the Lorsch Pharmacopoeia (around 800), ginger is included in about 10% of the 482 recipes, including potions, syrups, pills and powders for stomach and intestinal ailments, diseases of the liver, spleen and kidneys, and intermittent fever. Hildegard von Bingen devoted a differentiated consideration to ginger in Physica: For healthy and corpulent people, consumption is harmful, as the heat makes them thoughtless and hot-headed. However, for those who are dry in body and almost dying, ginger is life-saving. The Circa instans of the School of Salerno lists ginger as a digestive and carminative for cold stomach ailments, flatulence and fainting [Mersi 2011].

Its use for travel sickness, however, has only been documented since the 19th century. In his travelogue The Narrative of a Voyage to the Swan River (1831), John Giles Powell describes a glass of brandy with water, nutmeg and ginger as a remedy for seasickness. John Woodall's The Surgeon's Mate (1617), the standard work on English shipboard medicine, mentions ginger for colic and scurvy, but not yet for motion sickness [Powell 1831] [Woodall 1617].

Drug and ingredients

In May 2025, the Committee on Herbal Medicinal Products (HMPC) of the European Medicines Agency (EMA) published an updated monograph on ginger rhizome (Revision 1).

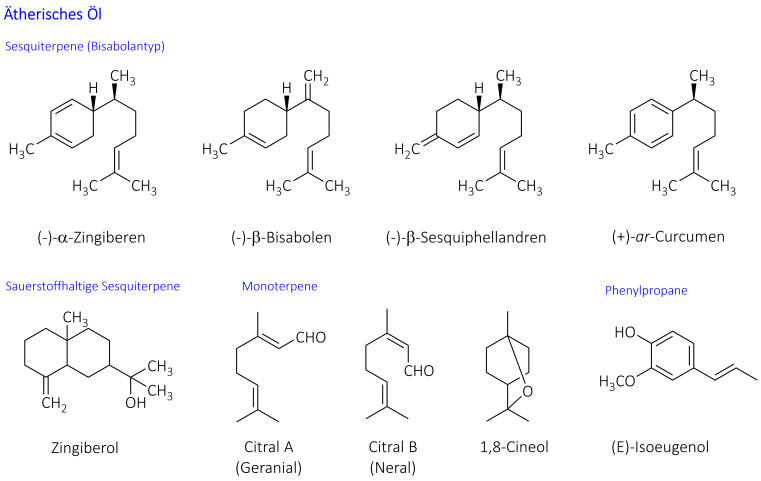

The quality of the drug (Zingiberis rhizoma) is described in the European Pharmacopoeia. The drug consists of the dried rhizomes, which have been completely or partially stripped of their cork, and contains at least 1.5% essential oil. The composition of this oil varies depending on the origin and chemotype. Sesquiterpenes such as (-)-alpha-zingiberene and (+)-ar-curcumene usually dominate. Zingiberol is responsible for the characteristic smell, while monoterpenes, especially citral, also contribute to the aroma [Wichtl 2016].

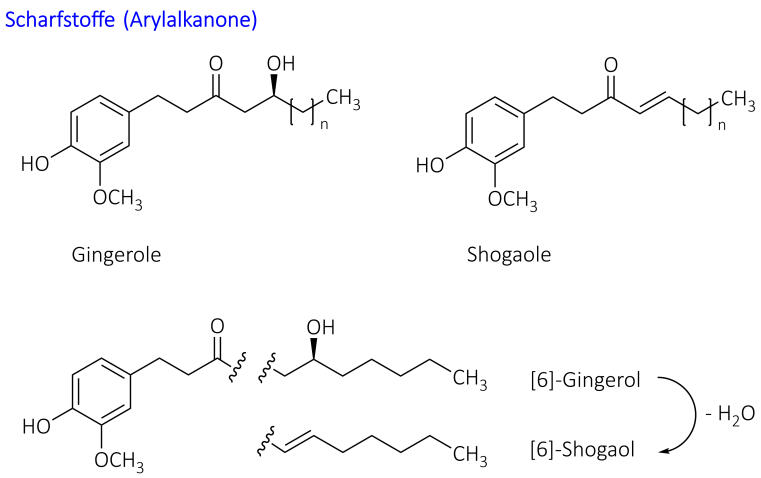

The non-volatile pungent substances (approx. 1-2%) belong to the group of arylalkanones. The main representatives are gingerols, among which [6]-gingerol dominates, as well as the more pungent shogaols, which are only formed from gingerols during storage through water separation. The degradation product zingerone has hardly any pungent taste. A higher content indicates overlaying [Wichtl 2016].

Quality variability is a significant problem: in a study of dietary supplements, the [6]-gingerol content varied between 0.0 and 9.43 mg/g. The majority of the products examined also had shogaol contents above the USP specifications, which indicates improper storage or processing [Hook 2025].

Effects

The antiemetic effect of ginger is based on an antagonistic effect on 5-HT3 receptors. In human pharmacological studies, ginger significantly increased phase III of the migrating motor complex with contractions and accelerated gastric emptying into the duodenum after eating [Wichtl 2016] [HMPC 2025].

Anti-inflammatory effects are mediated by inhibition of cyclooxygenase-1 and -2 as well as NO synthase. Gingerols are also potent vanilloid receptor agonists (VR1), which partly explains the analgesic effects. A blood pressure-lowering effect is associated with the blockade of voltage-dependent calcium channels [Wichtl 2016] [HMPC Assessment 2025].

Pharmacokinetic studies show rapid absorption of gingerols and shogaols, with maximum plasma concentrations reached within 30-75 minutes. Bioavailability is limited by extensive phase II metabolism, in particular glucuronide conjugation. Noteworthy are the observed multiple plasma concentration maxima, which indicate enterohepatic recirculation [HMPC Assessment 2025].

Indications

The updated HMPC monograph from 2025 distinguishes between well-established use and traditional use. The prevention of nausea and vomiting in motion sickness is considered a well-established use [HMPC 2025].

Five indications are listed for traditional use: (1) relief of symptoms of motion sickness, (2) symptomatic treatment of mild, cramp-like gastrointestinal complaints including bloating and flatulence, (3) temporary loss of appetite, (4) relief of mild joint pain, and (5) relief of cold symptoms. The last three indications were newly included in the 2025 revision [HMPC 2025].

The clinical evidence for the various indications varies in robustness: of 109 randomised controlled trials analysed, only 43 met the criterion of high evidence quality. The best data is available for gastrointestinal effects, morning sickness and as an adjuvant in chemotherapy-induced nausea. The results for motion sickness are model-dependent and not consistent [Hook 2025].

Preparations & Dosages

Well-established use (prevention of motion sickness): Adults 1-2 g powdered drug, 1 hour before departure. Use in children and adolescents under 18 years of age is not recommended due to insufficient data [HMPC 2025].

Traditional use (travel sickness): Adults and adolescents 500-750 mg, children 6-12 years 250-500 mg powdered drug, 1/2 hour before departure. For longer journeys, a further dose may be taken every 4 hours (maximum daily dose: adults 2.5 g, children 1.5 g) [HMPC 2025].

Traditional use (other indications): Powdered drug 0.18–1 g three times daily, alternatively tincture 1:10 (ethanol 90%) 1.5–3 ml three times daily or tincture 1:2 (ethanol 90%) 0.25–0.5 ml three times daily. Use in children and adolescents under 18 years of age is not recommended [HMPC 2025].

Finished medicinal products: Zintona capsules (250 mg ginger rhizome powder). Ginger tincture is a component of NRF 6.3 bitter tincture [Wichtl 2016].

Safety information

Adverse effects: Frequent gastrointestinal complaints such as upset stomach, belching, dyspepsia, heartburn and nausea. Hypersensitivity reactions are possible [HMPC 2025].

Pregnancy and lactation: Moderate data from human studies (300-1000 pregnancy outcomes) show no evidence of malformations or foetal/neonatal toxicity. Animal studies are insufficient with regard to reproductive toxicity. In rodents, increased embryo resorption was observed at doses in the range of or above the human therapeutic dose. As a precautionary measure, it is recommended to avoid use during pregnancy. There is insufficient data on use during breastfeeding [HMPC 2025].

Interactions: None known. In vitro studies suggest possible inhibition of CYP2C19 and P-glycoprotein. The clinical relevance is unclear. A clinical study showed no interaction with warfarin [HMPC Assessment 2025].

Sources

HMPC. European Union herbal monograph on Zingiber officinale Roscoe, rhizoma. EMA/HMPC/885789/2022, Revision 1, May 2025

HMPC. Assessment report on Zingiber officinale Roscoe, rhizoma. EMA/HMPC/765220/2022, Revision 1, May 2025

Hook I, Krenn L, Steinhoff B, Wolfram E. Factors Influencing Clinical Trials of Herbal Medicinal Products - Using Ginger as Example. Planta Med 2025; 91: 880-890

Mersi J. Ginger (Zingiber officinale ROSCOE) and galangal (Alpinia officinarum HANCE) in the history of European phytotherapy. Diss. Würzburg 2011

Powell JG. The narrative of a voyage to the Swan River. London 1831

Wichtl M (ed.). Tea Drugs and Phytopharmaceuticals. 6th edition. Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft, Stuttgart 2016. pp. 704-706

Woodall J. The Surgeon's Mate. London 1617

Chemical structures of relevant constituents