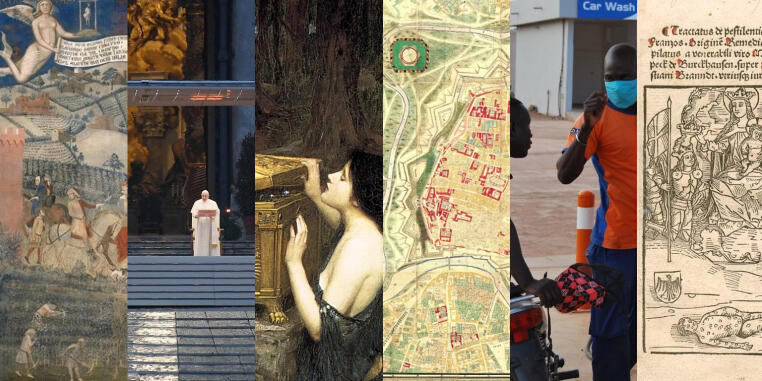

Space or: Distance and spread

Dossier "Epidemics. Perspectives from cultural studies"

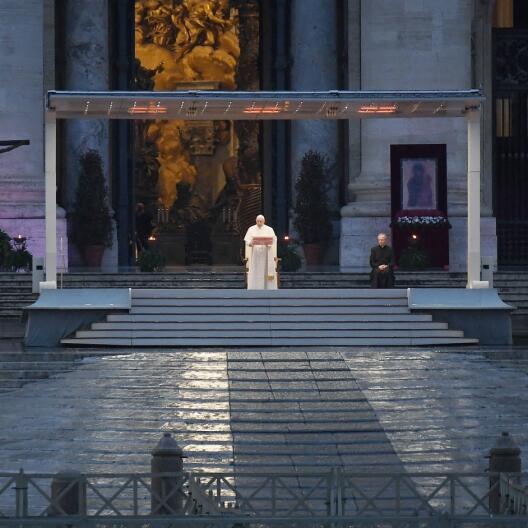

On 11 March 2020, the World Health Organization declared the spread of Covid-19 to be a pandemic. In response to a virus that made us aware of the global interconnectedness of our world by spreading across nations and continents, governments closed borders and imposed travel bans. Many people living in cities, and especially in metropolises such as Paris, London and Milan, fled to the countryside because the lower population density and greater proximity to nature made the risk of infection seem lower there. Also, the consequences of the lockdown (closed shops, cafés, museums, theatres and cinemas, empty pedestrian zones, deserted public places) were more apparent in the city than in the countryside. Since the gradual easing of lockdown restrictions, the unit to measure public spaces has been 1.5 metres, and markings on the ground and red-and-white barrier tape are omnipresent reminders of the need for us to keep our distance. Following the perspectives from cultural studies on the relationship between epidemics and time, the following contributions shed light on the changes that epidemics mean for spaces and how we perceive them.