Plague and urban areas: Vienna, 1679 (and 1713)

By art historian Jens Niebaum

The medical, administrative, religious, and cultural management of the great plague epidemics in the early-modern era was often inscribed in urban structures, which in turn shaped and reconstituted this management. A particularly good example is the imperial city of Vienna, which was hit by a particularly severe plague in 1679. The famous preacher Abraham a Sancta Clara vividly described “the grim death” in the Habsburg metropolis in his Mercks Wienn of 1680: “In Gentlemen Alley, death ruled ... In Singer Street, death sang the requiem to many ... On the Grave, death did nothing but bury. In Freyung, little was free of death … In short, there are no alleys or streets … either in Vienna or its large and wide surroundings that death has not ravaged”. As if the streets of Vienna were named after the way death had worked in them, the city, a space of secure, pulsating life, is reinterpreted as a space of death, one that not even the gentlemen in Gentlemen Alley can escape.

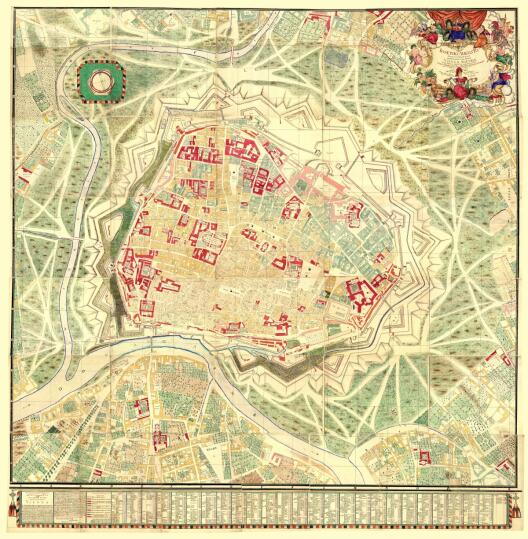

Vienna was sharply divided into two concentric spatial zones by a massive bastion and the firing range of the glacis around it: the inner city and a ring of unfortified towns. The measures, initially taken rather hesitantly in 1679, after the epidemic had first spread to the overcrowded slums and student halls of the surrounding towns, were aimed above all at protecting the inner city with St. Stephen’s Cathedral, the Hofburg, palaces, and monasteries. The attempt was made to remove or keep away from the urban space whatever was considered potentially dangerous: goods from infected areas, farm and street animals (deemed possible carriers), as well as beggars, who had always been suspected of encouraging the spread of the plague. Not unlike today, the emphasis was on spatial isolation by enforcing existing borders. And again not unlike today, this measure ultimately had only a delaying effect. The infirmary to which every sick person had to be transferred (and which very few left alive) was of course located far outside the city, in what is today Vienna’s ninth district; and even the most distinguished victims of the plague were not allowed to be buried in the hereditary burial places of the churches or in the city cemeteries, but had to be transported from the city as quickly as possible and buried in the nearest graveyard. Outside the city walls were also the huge plague pits, where the dead were brought on large funeral carts to be buried anonymously.

Such hotspots only became places of memory, if at all, much later. Contemporaries preferred to anchor the memory of the event by erecting a triumphal monument of the emperor in the inner city. After fleeing to Prague with a large retinue, Leopold I, at the insistence of the Lower Austrian government, vowed to erect a monument in honour of the Blessed Trinity on the Graben and to hold a commemorative mass every year. After a complicated history of planning and building, one punctuated by numerous breaks, an honorary column was finally erected in 1692. This presents below the Trinity the kneeling emperor as a pious intercessor of his lands, their coats of arms surrounding him, and, as a reward for his piety, depicts on the pedestal the victory of faith over the plague. It is a monument not to the many dead, but to the pious emperor’s blessed work for his subjects, erected in the centre of Vienna, on the most important processional route between the imperial Hofburg and St. Stephen’s Cathedral.

When only a few decades later, in 1713, Vienna was again struck by the plague, Emperor Charles VI, Leopold’s younger son and second in line, took this route to the Cathedral and vowed to construct a votive church in honour of St. Charles Borromeo, who was not only his patron saint but also one of the most important ‘plague saints’. Fischer von Erlach’s famous Karlskirche was built outside the walls, separated from them by the glacis, a strip of land left undeveloped for defence purposes. Vis-à-vis one of the most important gates (used, for example, for festive processions), it looked out like a watchman on the city opposite, as if it had been ordered to protect it. This appears in the gable relief behind depictions of dying and burial, while the intercession of St. Charles on the top has the plague extinguished. The emperor himself does not appear in the picture, but he does all the more monumentally in the symbolic figure of the two giant columns that frame it. These symbolize “firmness” and “strength” in his motto, and line people’s path to the church for prayer. In front of the church, there was originally the fallow land of the Glacis; later, the Karlsplatz developed here, one of Vienna’s newest urban centres. Even if few people today are perhaps aware of it, the plague and its consequences have also strongly inscribed themselves in the structure of the city.

Such hotspots only became places of memory, if at all, much later. Contemporaries preferred to anchor the memory of the event by erecting a triumphal monument of the emperor in the inner city. After fleeing to Prague with a large retinue, Leopold I, at the insistence of the Lower Austrian government, vowed to erect a monument in honour of the Blessed Trinity on the Graben and to hold a commemorative mass every year. After a complicated history of planning and building, one punctuated by numerous breaks, an honorary column was finally erected in 1692. This presents below the Trinity the kneeling emperor as a pious intercessor of his lands, their coats of arms surrounding him, and, as a reward for his piety, depicts on the pedestal the victory of faith over the plague. It is a monument not to the many dead, but to the pious emperor’s blessed work for his subjects, erected in the centre of Vienna, on the most important processional route between the imperial Hofburg and St. Stephen’s Cathedral.

When only a few decades later, in 1713, Vienna was again struck by the plague, Emperor Charles VI, Leopold’s younger son and second in line, took this route to the Cathedral and vowed to construct a votive church in honour of St. Charles Borromeo, who was not only his patron saint but also one of the most important ‘plague saints’. Fischer von Erlach’s famous Karlskirche was built outside the walls, separated from them by the glacis, a strip of land left undeveloped for defence purposes. Vis-à-vis one of the most important gates (used, for example, for festive processions), it looked out like a watchman on the city opposite, as if it had been ordered to protect it. This appears in the gable relief behind depictions of dying and burial, while the intercession of St. Charles on the top has the plague extinguished. The emperor himself does not appear in the picture, but he does all the more monumentally in the symbolic figure of the two giant columns that frame it. These symbolize “firmness” and “strength” in his motto, and line people’s path to the church for prayer. In front of the church, there was originally the fallow land of the Glacis; later, the Karlsplatz developed here, one of Vienna’s newest urban centres. Even if few people today are perhaps aware of it, the plague and its consequences have also strongly inscribed themselves in the structure of the city.