Poems against forgetting

By literary scholar Prof. Dr. Martina Wagner-Egelhaaf (German Studies)

Since the beginning of the Corona pandemic, we have been confronted with numbers: the number of those infected, the number of those who have died ‘with or from’ Corona, the number of cases. We are fascinated by the rising or falling numbers published daily by the Robert Koch Institute. When a lantern was lit for 1,000 victims at the Lincoln Memorial Reflecting Pool in Washington, it is at best a helpless attempt to at least reduce the frighteningly abstract and anonymous numbers to a manageable level. As President Steinmeier noted in his speech at the central memorial service on 18 April 2021 for those who had died in the Corona pandemic, people often fail to realize that behind the numbers are fates and people whose suffering and deaths remain invisible to the public.1 At the beginning of his speech, he placed lines of verse by Erich Mühsam (1878-1934), the anarchist poet who was murdered by the Nazis in the Oranienburg concentration camp in 1934. They read:

To whom can I lament

Who feels with me?

To whom can I tell

What rages within me?

These are only the first four lines of a longer poem that reads in its entirety:

Each one’s own

Suffering in the juices.

Some conceal it.

Some show it.

But the crowd forgets it in transactions.

Only those who love us

Will share with us.

Love forgives,

Love can heal.

I look back:

Once I was allowed to love.

But all my happiness

Has remained piece by piece

By the way.2

Obviously, words formed artistically help us find our own words. Steinmeier only quoted the first four lines, but the lines following could also be read as expressing the experience of suffering and loss, since the commemoration turns precisely against forgetting “in transactions”. And it is precisely here that sharing in the sign of love and human togetherness is important. Mühsam’s poem becomes personal in the last lines when he speaks in the first person of the loss of love. This may refer to the break-up of a love relationship. But it is precisely this loss of love that makes Mühsam’s poem seem particularly bleak and describes an experience that many people who have lost a beloved partner in the pandemic will relate to. Nevertheless, the power of a poem, even one quoted in excerpts, seems to lie in the fact that its words are spoken by a very specific person, in this case the highest representative of the state, in a very specific situation, and yet reach beyond that situation. In other words, the lines are not absorbed by, and therefore not lost in, the situation in which they are recited. When Steinmeier speaks the lines, he shares them with those he wants to reach, first and foremost in the present situation with the relatives and friends of those who have died in the pandemic. The sharing of supra-individual lines is a community-building sharing.

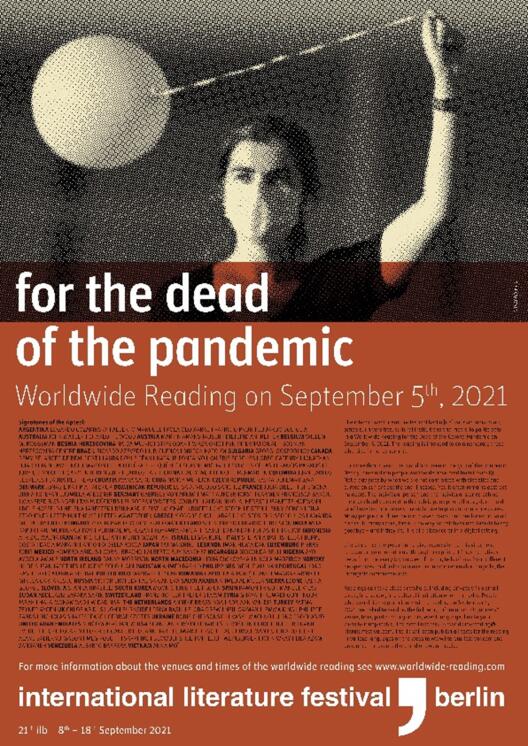

A similar idea underlies a Berlin Literature Festival project, which organized a worldwide reading for the Corona dead on 5 September 2021. Numerous authors from many different countries read or provided texts for the reading. They can be read on the internet, which is thus also becoming a kind of memorial site.3 Prose texts were read, but also a great many poems – in each case, the focus was on the artistic word, which evokes completely different ideas and images than rows of numbers, and is above all much less unambiguous and opens up spaces of thought. Literature interrupts the routines of everyday life and gives us pause. Literary texts, and poems in particular, want to be reread, they are meant to be memorized and in this way fulfil a specific function of memory. The moment they are shared and read or heard by others, they each take on an individual form and meaning – and yet always remain beyond, in that they also offer pause for thought and resistance. This is precisely what makes them monuments where memory happens and is renewed. In the Berlin literary project with the Icelandic writer Steinunn Sigurdardottir, we meet the grandmother of her friend Júlia, who died of covid; a poem by Edward Hirsch from the USA recalls eight deceased people from his block in seemingly godforsaken Brooklyn; and Forrest Gander, also from the USA, shares lines from which voices speak to us, from which we do not know exactly where they come, but which perhaps strike us all the more:

Aubade

Can you hear dawn edging close, hear * soft light with its vacuum fingertips * gripping the

bedroom wall, an understated * what? exhilaration? Can you hear the voices, * if they can

be called voices, of towhees * scratching in the garden and then * the creaky low husky *

voice flecked with sleep beside you in bed * telling a dream slowly as though in real time, *

and now, interrupting that dream, can you * make out the voice, if it can be * called a voice,

of absence speaking * intimately to you, directly, * using the names of those who were

vulnerable * those who have gone * I know you must * hear it feelingly, a low vibration in

* your bones, for don’t you find yourself * absorbed in a next moment beyond your given

life?

- 1See https://www.bundespraesident.de/SharedDocs/Reden/DE/Frank-Walter-Steinmeier/Reden/2021/04/210418-Corona-Gedenken.html (last accessed 16 November 2021).

- 2Erich Mühsam, „Wem kann ich klagen?“, in: Mühsam, Erich, Wüste, Krater, Wolken, Berlin 1914, 187.

- 3See https://zmi.literaturfestival.com/ilb/festival-en/projekte-en/weltweite-lesung-en/wwr%205.9.21/TextsfortheWorldwideReadingonSeptember5th2021.pdf/at_download/file (last accessed 15 June 2022).