In God’s Hands

Daniel Defoe's A Journal of the Plague Year Being Observations or Memorials, of the most Remarkable Occurrences as well Publick as Private, which happened in London during the last Great Visitation in 1665. Written by a Citizen who continued all the while in London. Never made publick before (1722)

By literary scholar Martina Wagner-Egelhaaf (German studies)

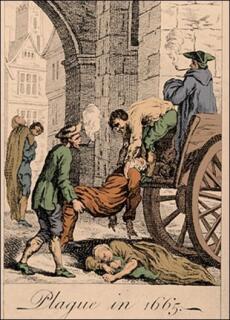

As close to the events and as documentary-like Defoe’s “Journal” might appear, it is nevertheless a fictional text written 67 years after the Great Plague that struck southern England and London in 1665/66. This outbreak of the plague was one of the last major plague epidemics in Europe, claiming around 100,000 lives. Even though Defoe’s account is an after-the-fact, fictional account, he used sources and statistics, and employed literary devices, to create the impression that he was a direct eye-witness. Although, as research has pointed out, the text adopts a sceptical attitude and focuses on medical, political and social phenomena that it views from the perspective of an enlightened rationalism, there are also numerous religious references, the narrator proving to be a representative of a rationalist understanding of religion.

The narrator reports that the outbreak of the plague in London saw many people leave the city. After a long internal struggle, he himself decides to stay, which in terms of narrative economy is of course necessary, for otherwise he would not be able to write his account. The decision, which he struggles with from time to time in the course of the report, is also made with God in mind, who obviously intended something with the outbreak of the plague:

It came very warmly into my Mind, one Morning, ... that as nothing attended us without the Direction or Permission of Divine Power, so these Disappointments must have something in them extraordinary; and I ought to consider whether it did not evidently point out, or intimate to me, that it was the Will of Heaven I should not go. It immediately follow’d in my Thoughts, that if it really was from God, that I should stay, he was able effectually to preserve me in the midst of all the Death and Danger that would surround me; and that if I attempted to secure my self by fleeing from my Habitation, and acted contrary to these Intimations, which I believed to be Divine, it was a kind of flying from God, and that he could cause his Justice to overtake me when and where he thought fit.

The imputation of a divine intention also causes the reflecting subject to make up his mind and take resolutions. We are indeed surprised that the narrator, who subsequently wanders through the city afflicted by contagion and death to take a close look at everything, is himself spared the plague, and indeed cannot explain this in any other way than that the rationalistic calculation cited comes true. The narrator thus has God’s will and guide on his side for his fictional project!

On his walks through the plague-infested city, he sees people suffering and marked by the physical signs of the plague, piles of dead bodies, and pits where hundreds of corpses are buried every day. And he reports of infected people throwing themselves out of agony and despair into the mass graves – “it was indeed very, very, very dreadful, and such as no Tongue can express” (70). But the city is also full of stories: for example, he has heard of a man who ran to the Thames in pain at night, threw off his nightgown, and swam the Thames twice, then lay down in his bed again – and was cured. However, he also reports that many delirious people had thrown themselves into the Thames and drowned, 20,000 people falling to their deaths in just one week. Defoe’s text is interspersed with tables depicting deaths that are quite reminiscent of notices of infection and mortality figures common in the current Corona epidemic. For example:

the Number in the Weekly Bill amounting to almost 40,000 from the 22nd of August, to the 26th of September, being but five Weeks, the particulars of the Bills are as follows, (viz.)

From August the 22nd to the 29th 7496

To the 5th of September 8252

To the 12th 7690

To the 19th 8297

To the 26th 6460

38195 (159).

It also reproduces ordinances issued by the London city government that are reminiscent of current measures, such as quarantine regulations, the obligation to report cases of illness, and the ban on festivities (see also the dossier “Precautions and Rules”). While praising the crisis management of the city of London as a whole, the narrator also takes issue, for example, with the measure of closing houses and having them guarded, as this meant that those infected were no longer allowed in their homes and had to stay on the street instead of being able to die in their beds. He also criticizes the fact that a city as large as London had only one plague house. The balance-sheet nature of Defoe’s journal is counterpointed by a multitude of anecdotes and stories about individual cases, as well as almost dramatic dialogues between individuals whom he meets.

Prevailing above all else, however, is “the Hand of God” (49, 74, 163 passim), which is probably the metaphor used most frequently in the text. The hand of God gives and takes away (see also the article by Jens Niebaum in this dossier). However, Defoe’s narrator also reports how those who doubt the rationality of God surrender to superstition and magical practices, with people’s powers of fancy running amok. Sects sprang up, belief in devils flourished, as did astrology. He says of himself that he could not entirely rid himself of the belief then widespread that the appearance of two comets came “as the Forerunners and Warnings of God’s Judgments” (39). People tried to banish the evil by means of magical signs, such as

He also reports that many began to blaspheme God, while others continued to attend church services faithfully, if they still took place at all. He himself criticizes the clergy, who in their sermons terrified people by pointing to their sins, and he points instead to God’s love and mercy. It is precisely this trust in God that gives him legitimacy as a narrative guide through the London plague. While paying respect to the work of doctors who were risking their lives to help the sick, he is forced to conclude that they were essentially powerless against “God’s Judgment” and the “Distemper eminently armed from Heaven” (51).

“However it pleas’d God by the continuing of the Winter Weather to restore the Health of the City, that by February following, we reckon’d the Distemper quite ceas’d” (206), the journal finally says. As in other literary narratives about an epidemic, the sick then recover very quickly. Healing processes are obviously less fertile from a narrative point of view than the drama of an epidemic spreading. Despite all the suffering and misery he had to endure and document, the chronicler has nothing left at the end but to thank God for putting an end to the plague. And so the text concludes in a manner that is almost cheerful:

A dreadful Plague in London was,

In the Year Sixty Five,

Which swept an Hundred Thousand Souls

Away: Yet I alive! (211)