Hostile Terrain 94: Resisting the "Spectacle of Numbers" with Toe Tags

Since 2000, more than six million people have attempted to cross the U.S.-Mexican border through the Sonoran Desert.

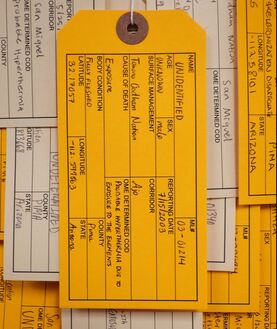

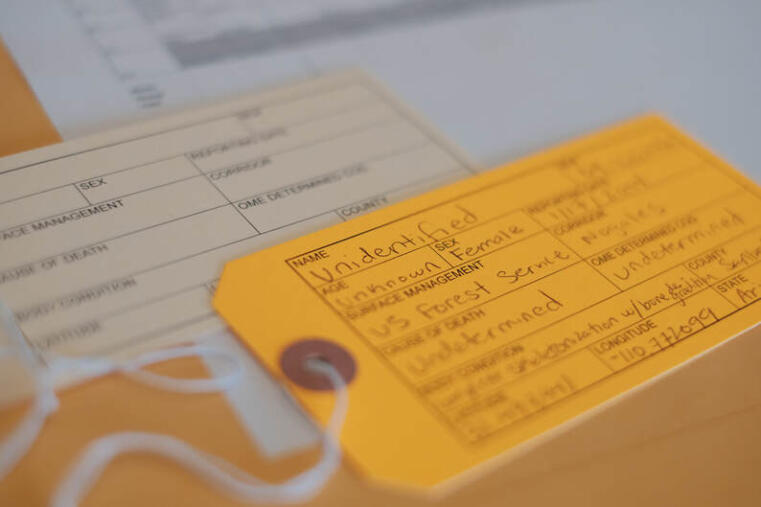

At least 3,200 of them have died during their journey. Their remains were found in the vast and harsh terrain of the Borderlands and were then clinically recorded in databanks by medical examiners. While they are missed and mourned by family and friends, for most of us, these deaths are invisible, non-existent in a sense because their lives are officially framed to be “ungrievable”. After all, the killing that happens in the desert on a regular basis is not only tacitly accepted by the US government, but a direct consequence of US border politics. “Hostile Terrain 94” seeks to resist the absence of human decency in the way borders are enforced and human beings are punished for “illegally” transgressing borders even beyond their death. At the core of HT94 are volunteers manually filling out 3,200 toe tags that represent the 3,200 migrants who lost their lives trying to cross the border. The arduous task of writing out the details of each perished individual is an act of honoring and commemorating despite not knowing them. The handwritten toe tags are then pinned to the wall map with meticulous precision to ensure that the spot shows the exact geographic location from which each individual’s remains were recovered.

When it comes to flight and migration, numbers often dominate the public debate in media and political discourses. The “dramatically rising” numbers of “illegal” migrants currently on the move, the number of people that are expected to be arriving soon, the number of people that have been received so far, the number of refugees that can stay or are deported. The focus on numbers can be related to the “spectacle of statistics” [1] which contributes to framing illegalized migration as a “crisis” and “illegal” migrants as a menace. Thought of as a number, migrants on the move can be constructed as a dehumanized “mass”, an “influx” or a “stream” that must be repelled or regulated – a framing of migration that stands in stark contrast to the way in which the US idealizes its genocidal settler colonialism. The “spectacle of statistics” obscures not only the fates of individuals, but also the political turmoil and economic disasters that cause people to seek refuge elsewhere. Root causes are inextricably linked to US interventionist foreign policy in Central and South America which, since the 1960s, has been marked by total disregard for democratic structures and human rights. The focus on numbers makes it possible to externalize US American historical responsibility for the causes of migration because the “spectacle of statistics” is about justifying political measures to put just our own house in order.

For Hostile Terrain 94, Jason de León, director of the Undocumented Migration Project (UMP), used data provided by Humane Borders, a non-profit corporation, and the Pima County Medical Examiner’s Office in Arizona. Based on this data, Humane Borders creates Migrant Death Maps: maps with red dots that indicate the place where perished migrants were found and provide more information about them. However, Jason felt the need to visualize the data differently, not as numbers or as red dots, but in a way that would allow envisioning the humans behind border deaths. Therefore, for Hostile Terrain 94, the data is transferred onto toe tags by the volunteers.

Hostile Terrain 94 seeks to humanize the data by translating it into a community-based practice of counter-remembrance, that is, of commemoration as resistance to the “ungrievability” of migrants. According to Judith Butler [2], “grievability is a condition of a life’s emergence and sustenance”. A grievable life is one that is livable because it is valued and sustained by systems of support and regard. And once this life has been lived and ends, it can be mourned as a life lost. Ungrievable lives, on the other hand, are lives “that will never have been lived” since they receive no regard and no support. This means that an “ungrievable life is one that cannot be mourned because it has never lived, that is, it has never counted as a life at all”. Migrant lives are thus often “ungrievable” lives: they are less valued, considered less worthy of support and protection, are less regarded as livable. This is reflected in the “spectacle of statistics”. Having toe tags filled out by volunteers will not rectify how these human beings have been systematically failed while alive. But it is a commemorative practice that resists the “differential distribution of public grieving” which regulates who can be recognized as a subject with rights and a life that is deemed officially mourn-able.

With HT94, each of the 3,200 border crossers’ lives will be considered by over 100 volunteers in the over 100 HT94 hosting locations around the world, their details will be written down over 100 times, their tags will be held by over 100 hands before being put on public display for others to view them, too. The aim is to restore to these people in death what has been taken away from them in their lives as illegalized migrants: recognition, value, regard, and a sense of identity as much as possible. Jason de León explains: “I wanted to put names to the dead. This is an act of witnessing. The data come from a Microsoft database. We’re asking volunteers to breathe life into the data by writing out the details. That was the closest way we could think of to get someone to feel the human cost” [3].

The human cost of anti-immigration policies, masked as “border security” measures, become especially clear when we look at toe tags and how they document what little remains from undocumented migrants’ lives in a society that deems them ungrievable.

Toe tags are pieces of cardboard used in morgues and tied to the big toe of a deceased person to identify them. You can read on the Hostile Terrain 94 toe tags about the name, age, sex, reporting date, the exact location place where the body was found, cause of death and the condition of the body. The manila toe tags represent people whose names we know. The orange toe tags represent migrants who could not be identified, and whose unknown fate constitutes a catastrophe for the families and friends they leave behind. This lack of data that can be used for identification is not coincidental but a direct consequence of the deadly border politics in the US: Many migrants travel without identifying documents so that they will not have to identify themselves when apprehended by border police. Additionally, bodies deteriorate very quickly in the desert, making it at times impossible for families to identify them. Thus, toe tags sometimes only reveal the barest minimum of information about a person, such as the reporting date and the place where their remains were found.

Despite this, volunteers all over the world commit to invest time and effort in filling out the toe tags with all information available. Each filled-out toe tag says that migrants who die at the border are more than a number, that they constitute a humanitarian crisis. Manila-coloured tags sometimes allow us to get a fleeting impression of the persons they represent when name and age conjure a face and a possible story. Orange toe tags remind us that the desert is a harsh terrain that leaves just traces of a human being after the shortest time of exposure to its hostility, making them unidentifiable. Behind every toe tag, there is the effort to not take part in the “spectacle of statistics”, but to draw attention to the extraordinary precarity in which illegalized migrants constantly find themselves while alive and to the violence of “distributional grieving” through which they are denied recognition and visibility even after their death.

[1] De Genova, Nicholas, Heller, Charles, and Maurice Stierl. “Numbers (or, The Spectacle of Statistics in the Production of ‘Crisis’)”. http://nearfuturesonline.org/europecrisis-new-keywords-of-crisis-in-and-of-europe-part-4/

[2] Butler, Judith. “Precariousness and Grievability—When Is Life Grievable?”. Verso, https://www.versobooks.com/blogs/2339-judith-butler-precariousness-and-grievability-when-is-life-grievable.

[3] Aviles, Mary. “Data Visualization as an Act of Witnessing”. Nightingale. The Journal of the Data Visualization Society, 4 March 2020, https://medium.com/nightingale/data-visualization-as-an-act-of-witnessing-33e346f5e437