The Hostile Terrain 94 Map: Borders are more than lines on a map

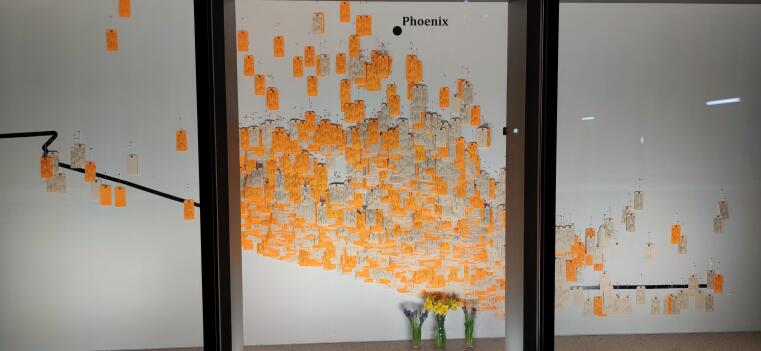

The Hostile Terrain 94 installation shows a wall map of the US-Mexican border as it crosses the Sonoran Desert of Arizona.

This map has barely any resemblance to the kind of maps that we encounter in school atlases or in the media. For example, it does not indicate particular features of the desert’s surface property by using blue to represent bodies of water or a shade of brown for higher surface elevations. What the HT94 map shows is empty space cut through by a bold black line: the border. In the bottom right corner, there is an indication of the scale of the bold black line in relation to its real-world counterpart. Black dots in the empty space point to two of the bigger cities in Arizona. Equipped with only a minimum of features that allow for geographic localization, the question arises as to what this map tries to “do” if not providing detailed surface property descriptions or orientation. As a “counter-map” the HT94 map seeks to expose what is obliterated by conventional maps, thus commemorating those whose lives are obliterated in the desert.

Conventional geographical maps, think of school atlas maps as a prime example, create the impression that they represent reality, the world as it is. With their surface property descriptions, their yellows, blues, greens, we assume that those maps are objective and neutral depictions of our surroundings. Yet, cartography, the science and technique of depicting geo-spatial information, has always been intricately tied to political agendas and the striving for power.

One of the basic principles of Critical Cartography is that maps do not simply show the world we live in but help to construct it in the first place.

For example, cartography has been a tool for colonial powers to seize control over foreign lands and their peoples. As Ila Sheren writes: “maps had become inextricably linked with empire and warfare by the fifteenth century. Originally, the very act of mapping a newly ‘discovered’ territory was ground enough for claiming it” [1]. Maps also played a significant role in the formation of nation-states as they managed to depict the world just like nations sought to see it: a world made up out of many clearly separated nation-state “containers”. Where there might only have been an informal border before, the nation-state map now showed a bold black line on paper and made the separation between distinct nation-states and between “us here” and “them over there” official.

Maps therefore create a hegemonic view of the world, a view focused on the dominant position of a particular power. Critical cartographers, including scientists, activists and artists, began to react to this with the practice of “counter-mapping” in the 1990s. With this critical practice, they sought to depict what hegemonic maps left invisible. The collective orangotango+ created an alternative atlas with “counter-maps'” only: maps of migratory routes through the Mediterranean Sea or of a Lebanese refugee camp, a map illustrating the problem of vacant buildings in New York, or one that shows the conflict of interest among different parties involved in a street protest. The collective explains: “we need to produce counter-maps in order to create actions that might affect our perceptions of social space and its different vectors, to change our modes of looking at the world and create new dialogues and discoveries'” [2]. Counter-maps are not meant to be the end-product of Critical Cartography. Rather, they can be understood as an expression of dissent against authorities that use maps to control space and the people therein, and as an incentive to view the world more critically and with a concern for the blank spots which hegemonic maps create.

How about the map of the Hostile Terrain 94 installation?

On the one hand, it depicts the border as a bold black line reminiscent of border depictions in hegemonic nation-state maps, and therefore it reproduces a worldview that insists on demarcations. Consequently, this is a worldview that frames people as “illegal” simply because they do not possess the right documents or the right status needed to cross certain boundaries. On the other hand, the HT94 map shows something, or rather someone, that is missing in hegemonic maps and that we are thus mostly oblivious of: people dying at the border. When the Hostile Terrain 94 exhibition opens and the first visitors make their way to the inner courtyard of the Bible Museum, they will find that the large wall map of the installation is still empty. Hostile Terrain 94 is an artwork in the making based on mapping as a practice of commemoration. The toe tags representing the undocumented migrants who perished along the border are pinned to the wall map little by little, filling the emptiness on the map gradually. The initial emptiness of the map mirrors the invisibility which characterizes so many refugees’ and migrants’ fates. The toe tags mounted to the wall map are meant to make these fates more visible.

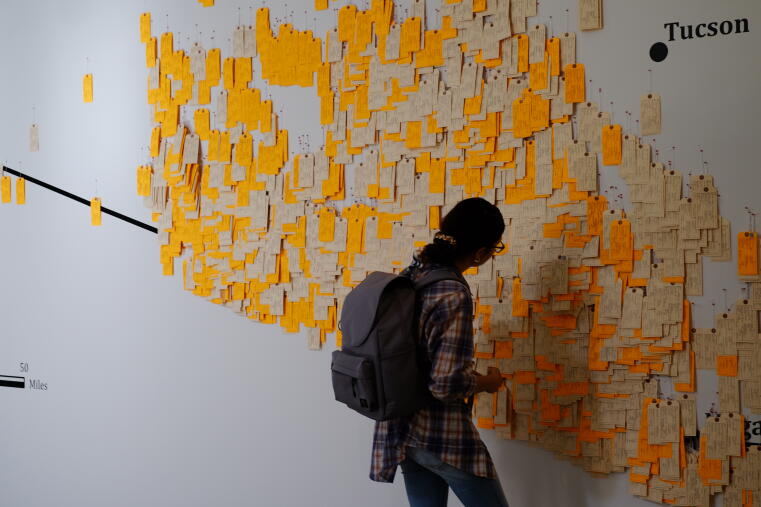

Standing in front of the finished wall map, we can hardly make out the border line anymore as it is covered by thousands of toe tags.

We can see toe tags on top of toe tags on top of more toe tags. Pinned to those places in the desert where many migrants died, the layered toe tags protrude from the wall map prominently. In other spots on the map, there are just a few toe tags. Together, the over 3,200 toe tags create a relief, a depiction of perished migrants that reminds us of the geographical depiction of the earth surface’s terrain. Yet, instead of depicting mountains and valleys, the HT94 map shows a terrain made up out of border deaths. As a counter-map, this installation seeks to make those border deaths visible and to encourage us to view cross-border migration in a more nuanced way: Not as a “wave of refugees” that threatens to roll over borders, or as a “mass” of refugees invading the country. The HT94 map shows that for many migrants the border is not a threshold that can be easily stepped over on the way to a new and hopefully better life, but it is a dead end – quite literally. The border itself is not responsible for this. Border deaths are the consequence of inhumane border politics such as the “Prevention through Deterrence” strategy used at the US-Mexico border. The HT94 map aims to raise awareness about the fact that borders are not as innocent as they appear on maps but go along with a worldview in which it is accepted that humans die at borders.

[1] Sheren, Ila Nicole. Portable Borders: Performance Art and Politics on the U.S. Frontera Since 1984. University of Texas Press, 2015. p. 78.

[2] kollektiv orangotango+, editor. This Is Not an Atlas: A Global Collection of Counter-Cartographies. First edition. Transcript, 2018. Sozial- Und Kulturgeographie volume 26. p. 30.