Conspiracy theories as narratives

By literary scholar Christian Sieg

Conspiracy theorists know more. What they know is a secret agenda that explains events or situations. At the moment they know that the reactions of the world community to the corona pandemic are based on misinformation that is part of a political or economic plan hatched by conspirators. We speak of conspiracy theories because, by their own claim, such statements try to explain something. But it might be more appropriate to speak of conspiracy narratives, since the knowledge that they provide is of a narrative nature. A situation or event is causally attributed to the actions of a group of people. The attacks of 9/11 were carried out by the Israeli secret service Mossad, and the French Revolution by the Illuminati – this is what is whispered in the conspiracy theory channels. If we consider conspiracy theories as narratives, one figure surprisingly appears in a new light: the conspiracy theorist. What advantages are there in understanding him or her as a narrator?

At first glance, the narrative dimension of conspiracy theories seems easy to grasp. Because conspiracy theorists report on how actors cause a certain event or situation, their report is a narrative. The function of narratives to create causal links is often emphasized in narrative theory. Narratives not only have a chronological order that simply lists events. They also link these events causally. In the terminology of E.M. Forster, literary studies refers to this aspect of narratives as plot. “The king died and then the queen died of grief” – this is Forster’s example of a plot. Now, as we know, not all queens are fictional. The same is true of factual narratives. We also use narratives to communicate about facts, to orient ourselves in the world, in our own lives, and in history. Whether an element of a plot is fiction or fact can only be checked in individual cases. Conspiracy narratives are also distinguished by the fact that they belong to those narratives that create a dichotomous worldview. In the storyworld of conspiracy theorists, conspirators differ from all other groups because of the power and moral ruthlessness attributed to them. The dichotomous order of the storyworld, where the group of conspirators faces the morally honest people, also explains why conspiracy narratives are so attractive to populist parties. Such attributions gain plausibility in times when moralistic views dominate and powerful groups of people are trusted with running everything. The villains of such narratives are well known: the CIA, Mossad, “the Russians”, or even Donald Trump. The plausibility of conspiracy narratives is based on numerous other fictional and factual narratives that depict actors in a way that conspiracy theorists can relate to. The narratological concept of a transmedial storyworld conceptualizes this link. It was developed to analyze transmedial narrative universes that no longer feed on a single text or film narrative. Thus, George Lucasʼ fictional characters in the Star Wars saga exist not only in his films, but also in numerous other adaptations in film, comics, computer games, and other games, as well as several other media. Recipients imagine a transmedial storyworld across all media boundaries. In other words, a storyworld is a mental model that is evoked as soon as an object is interpreted as a narrative. Storyworlds are no less important for conspiracy narratives. Whether actors are plausible as protagonists in conspiracy narratives also depends on how they are presented in numerous other narratives and the place that they occupy in transmedial storyworlds. The choice falls more on Donald Trump than on Angela Merkel. The narratological concept of the transmedial storyworld helps us to understand the dynamics of conspiracy narratives better. The concept names the imaginative narrative universe in which new narratives are created and their plausibility decided upon.

‘Narrative’ has so far been defined as a form of representation that causally links events and, in the case of a conspiracy narrative, ascribes to agents a special power and unscrupulousness. But that is not the only meaning of ‘narrative’. Gérard Genette distinguishes three dimensions of the term. By ‘narrative’, we mean, firstly, a narrative statement in written or oral form that conveys a particular object – for example, the deeds of a hero. Secondly, the term refers to the sequence of events depicted. The third sense of ‘narrative’ must be distinguished from this: it is the act of narration itself. Conspiracy theorists tell other people about a conspiracy. This statement may seem banal, but it does explain, at least tentatively, that conspiracy narratives, as actions, define identities.

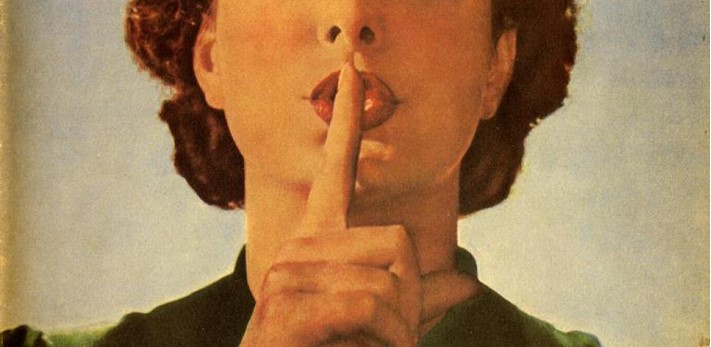

As soon as the analysis of conspiracy narratives focuses on the act of narration, the social dimension of narration becomes apparent. Narrations are acts of communication and as such they are never unconditional, but always refer to previous communication. In order to understand better the nature of communication about conspiracies, conspiratorial communication itself must first be understood, and research on the 18th century carried out in literary and cultural studies offers numerous insights here. For, paradoxically, the century of the Enlightenment was one of the heydays of the secret society. What characterized the lodges of the Enlightenment and counter-Enlightenment was their esoteric manner of communication. Conspiratorial networks communicate their knowledge only among insiders. Initiation into the secret society therefore plays a central role in the fiction. The popular secret-society novels of the time are also Bildungsromane in which young men experience their initiation into the circle of the knowing. Linda Simonis has shown that the esoteric manner of speaking has a performative dimension. It is not the content of the statement that is of primary interest, but rather the social impact inherent in this praxis of speech: the demarcation between the knowing and the non-knowing. Esoteric communication constitutes groups. For Simonis, this esoteric concept can already be found in Mark 4: 11-12: “The secret of the kingdom of God has been given to you. But to those on the outside everything is said in parables so that they may be ever seeing but never perceiving, and ever hearing but never understanding”. The secret-society novel of the 18th century seeks to reveal this mystery – to bring light into the darkness. While all secret-society novels and their adaptations in the medium of film have this enlightening emphasis in common, classics of the genre such as Friedrich Schiller’s Der Geistereher (1787/89) and Carl August Grosse’s Der Genius (1791/95) are also fascinated by the secret society. The narrator in each novel seeks to uncover the conspiracy, but at the same time conveys a sense of awe before it. In Grosse’s novel, the narrator is irresistibly drawn to the mystery; and even Schiller’s novel, long considered an enlightened example of the genre, is characterized by a rhetorical and aesthetic complicity with its subject.

Does this apply only to fiction? Is the secret only ambiguously presented in fictional genres? Not at all. The complicity between conspiracy and conspiracy theorists is also evident in the performative dimension of narratives with a factual claim. Certainly, the statements about the esoteric mode of communication referred to above apply to the circle of initiates, i.e. the conspirators and not the conspiracy theorists. But should these theses not also refer to the latter? Such a debate seems fruitful to me. This is supported by the fact that, as the secret-society novels from the 18th century also demonstrate, the enlighteners of conspiracy not only form a sworn community themselves, but also loudly complain that all others do not see with seeing eyes. The conspiracy theorists claim that they alone recognize the signs of the conspiracy and do not misjudge the obvious. Their marginalization is part of their own narrative, which always also reports that the power of the conspiracy is so great that all means are used to prevent enlightenment. Thus, knowledge of the conspiracy is not characterized as secret knowledge; rather, it is fundamentally accessible to everyone, but very much as the object of esoteric communication against one’s will. According to this narrative, the object to be uncovered is not secret, but hidden. Simonis refers here to Hegel: “The esoteric is the speculative, which, even though written and printed, is yet, without being any secret, hidden from those who have not sufficient interest in it to exert themselves” (Lectures on the History of Philosophy, translated by E.S. Haldane and Frances H. Simson). Esoteric communication does not require a ban on communication, but always stages why the circle of those in the know remains small, even though the secret is public. Unlike scientific communication, which not everyone can participate in due to their different educational biographies, conspiracy narratives name a reason why their knowledge is necessarily only accessible to a small circle: it is the conspirators who make sure of this! Thus, the narrative of the conspiracy immunizes itself against objections. Anyone who doubts its plausibility is simply blinded. Pointing to the lack of plausibility of their narrative therefore rarely convinces conspiracy theorists. The conspiracy narrative can always be expanded; indeed, if it is doubted, then it needs to be retold. This serial narrative praxis always generates the experience for narrators that, in contrast to all the others, they see through the context of delusion. With every new story told according to a familiar narrative pattern, conspiracy theorists present themselves as people who know, and want to be understood as the real representatives of all those who allow themselves to be blinded. They alone speak for the people, who are always deceived.

The fascination that conspiracy narratives hold can probably be explained to a not insignificant extent by this identity-forming function that the narrator has – and, unlike in fiction, the narrator of a narrative with a claim to factuality is a real person. It therefore seems necessary to me from a theoretical perspective to see communication not as a unidirectional process. If the sender-receiver model in communication theory conceives of the sender as an invariant, then narrative theory allows communication to be understood as an action that always also affects the actor. The position of the narrator is key to understanding the function of conspiracy narratives in our society. It is often observed in the current debate that conspiracy theories are received very favourably in esoteric circles. This can be explained if we understand these theories as narratives: conspiracy narratives stage their narrators in an esoteric manner.