Religion and politics at the Golden Horn? Turning over a new leaf on the Hagia Sophia

By Byzantinist Prof. Dr. Michael Grünbart

On 10 July 2020, the Supreme Administrative Court of Turkey ruled that the Hagia Sophia (Ayasofya) in İstanbul will become a mosque again. This undertaking is to become manifest at a Friday prayer on 24 July. This move of the Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan triggered violent, but also moderate reactions from political and religious representatives. Actually, this is less a religious matter – the Hagia Sophia has not been a Christian church for more than 550 years – than national(istic) affectivity.

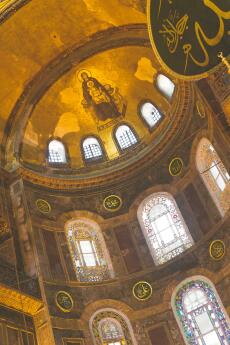

Hagia Sophia had been the Eastern Roman Empire’s space of identification since the 6th century: it was a place of assembly, religious service, decision-making and performance: Emperor Justinian, who had the church rebuilt after it was destroyed by fire in 532, is inseparably connected with the Constantinopolitan building. Both the architectural construction and the design of the interior make Hagia Sophia an impressive artistic synthesis in which, depending on the season, the conditions of illumination allow the marble-clad walls and the millions of golden tesserae to appear in the most diverse nuances. It is no wonder that more than 3.7 million visitors (2019) came to see the architectural masterpiece, happily spending TL 100 (approx. € 13) for one ticket.

However, between the 6th and 21st centuries, the church, which was consecrated to the Holy Wisdom, underwent interior and exterior changes. The building withstood storms, fires and earthquakes; it saw looting, imperial coronations, desecration and rededication; it was a bastion and a place of refuge, a market and a meeting place for the masses, as well as a space for political staging. Hagia Sophia was admired and imitated and served as a benchmark.

With the fall of Constantinople (1453), the most important Orthodox church was converted into a mosque by the Ottoman Sultan Mehmet II. The victorious new ruler had taken over not only the centre of the Eastern Roman Empire but also the title of imperator. He had the Patriarchate moved – today, the Church of St George is the seat of the Ecumenical Patriarchate under Bartholomew I – and a new head appointed who was critical of the Church Union, whereby the Orthodox faithful were offered continuity despite Muslim supremacy. Large parts of the magnificent decoration gradually disappeared behind plaster and under carpets. However, Hagia Sophia was not silenced: it influenced the architecture of the buildings of Ottoman architects such as Atik Sinan (Fatih-Camii, 1471) and Sinan (Süleymaniye Camii, 1550–1557) and had an impact on neo-Byzantine churches such as that of Saint Sava in Belgrade (completed in 2018).

Hagia Sophia served as a mosque for centuries, but still remained a place of longing and identification of the Orthodox world. For the Ottoman Sultanate, too, the possession of the church meant a precious good that had to be protected. Its importance made Hagia Sophia the headquarters of the Ottoman caliphate in the 16th century; its preservation kept the memory of Mehmet the “conqueror” alive. Necessary restoration work in the 17th and 18th centuries made the mosaic decorations increasingly disappear, but at the same time they were preserved. During the 17th century, the Patriarchate of Constantinople intensified relations with Moscow (itself a patriarchate since 1589) and hoped for support from the Russian Tsar and Great Duke Alexei Mikhailovich (1645–1676) – but no Christian Emperor returned to the Golden Horn.

With the end of the Ottoman Empire and the secularisation of the state by Mustafa Kemal Pasha (1881–1938) – born in Thessalonike (Selânik) and known as Kemal Atatürk from 1935 – a fresh wind blew, traditions were reassessed and changes were introduced. In 1923, the capital was moved to Ankara and Konstantîniyye became İstanbul. In the early 1930s, an American scholar arrived at the Golden Horn: Through his friendship with Kemal, Thomas Whittemore (1871–1950), initiator of the Byzantine Institute of America, was able to achieve that Hagia Sophia lost its status as a mosque (24 November 1934) and was opened to the public after restoration and excavation work. The museum was inaugurated by Kemal, now Atatürk, on 1 February 1935. The floor, which had been covered with carpets for centuries, shone. Since then, Hagia Sophia has been accepted by all sides as a neutral, non-religious space. Like his predecessor, Pope Francis visited Hagia Sophia and was received there by the director of the museum. It was only in the last 10 years that the instrumentalisation of the museum began to become increasingly apparent, serving the political powers that be to raise their profile. It is not surprising that the decision came now. It was well prepared and has several reasons: the Turkish president stages himself as victorious. The conquest of Constantinople in 1453 is commemorated every year. In 2019, the Çamlıca mosque, the largest in the country, was opened in İstanbul: the 107.1-metre-high minarets are meant to be reminiscent of the Seljuk victory against the Byzantines in Mantzikert (1071). This approach also shows how historical events can arbitrarily amalgamate into a politically appropriate narrative.

Adding to this is the strong domestic political influence of the right-wing National Movement Party under Devlet Bahçeli, who was once an opponent, but is currently an ally of the Turkish president. He has now taken the side of those supporting the conversion of the museum. The towering figure of Atatürk, however, is also increasingly eroding: the new presidential palace in Ankara surpasses that of the Turkish state founder; the airport named after him has been closed and a new one built. It is no more than a logical consequence that Kemal Atatürk’s signature on the 1934 Conversion Decree was declared to be revoked.

So what is the last word on the subject? While the conversion of the Hagia Sophia of Trabzon into a mosque had been cancelled again, the decision in İstanbul seems to be lasting. Visitors to the former homepage of Ayasofya Müzesi come to the Hagia Sophia Mosque, find that admission is free and the prayer times valid for İstanbul are pointed out to them.