Already 300 years ago: Epidemics and conspiracy theories

Little-known case shows “startling parallels to today” – Historian reconstructs emergence in England of conspiracy theories on plague outbreak in Marseilles in 1720 – heated debates and criticism of measures taken – “Richard Mead was ‘the Christian Drosten’ of the 18th century

Press release of July 17, 2020

According to historians, conspiracy theorists who do not believe in the pandemic already existed exactly 300 years ago. “When the plague broke out in Marseilles in 1720, England took extensive quarantine measures, provoking heated debates that were tainted with conspiracy theories. This little-known case shows startling parallels to present-day Germany”, writes historian André Krischer from the University of Münster’s Cluster of Excellence “Religion and Politics”. “Where today ‘corona demos’ rage against a ‘New World Order’ led by Bill Gates, rumours were circulating 300 years ago about the dark machinations of state, which it was said would curtail liberties, employ the military internally, and separate families”. Critics deemed every preventive measure to be unnecessary. “Some even thought that the epidemic could do absolutely nothing to harm the British”. According to Krischer, that measures to prevent the spread of disease rouses conspiracy theorists into action is something repeated in history: “Paranoid fear about the establishment of a dictatorship, fear of economic collapse, and a natural scientist at the centre of criticism – the English debate from the 18th century resembles our German present day in this respect, too”.

Krischer examines the historical case and structural similarities to the present in an article in German language entitled Willkürherrschaft und Strafe Gottes “Arbitrary rule and divine punishment” in the “Epidemics” dossier on the Cluster of Excellence website. He describes the similarities using a variety of sources and incidents – for example, a pamphlet by the Bishop of London, Edmund Gibson (1669-1748), who condemned rampant “lies and misrepresentations of facts” among his contemporaries. In another article, Krischer writes together with his colleagues Wolfram Drews and Marcel Bubert about the long tradition of “conspiracy theories as criticism of elites”.

Richard Mead – 'the Christian Drosten' of the 18th century

It is no coincidence, Krischer argues, that emotions should have become so heated in the 18th century, and precisely in England. “London already had in 1720 a very self-confident public with coffee houses and a uniquely diverse press and media landscape that was no longer regulated by censorship”. In addition, conspiracy theories had a long tradition in England, which was also suffering at the time from the bursting of the biggest speculation bubble of the early-modern period: “People thought constantly in terms of conspiracy theories: they were either afraid of being infiltrated by ‘papists’, i.e. Catholics, or they assumed that whoever was in power at the time wanted to establish an arbitrary government”. According to Krischer, the government’s measures were also contested on the side of religion, too, with the pulpits proclaiming the plague to be a punishment from God, and especially for London, that cesspool of unbelievers. The only way to counter the plague was to fast, pray, pay penance, and prepare calmly for death.

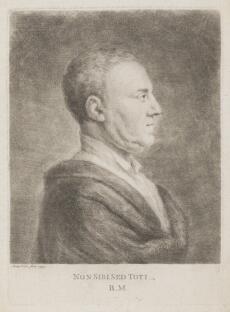

Like the German virologist Christian Drosten today, the target of the debate in 1720 was a physician, Richard Mead (1673-1754), whom many contemporaries mistrusted because of his closeness to politics, his religion (Mead was a Quaker and not an Anglican), and his strict recommendations on containing the plague. “In 1720, there was a dispute about the point of quarantine because there were still many doctors who did not believe that the plague was contagious. In 2020, schools and kindergartens were closed, while there was still controversy over whether children were relevant vectors for the corona virus”. If expert opinions that are scientifically uncertain become politically relevant, and can also be identified with a particular person (such as the virologist Christian Drosten in 2020 and the epidemiologist Richard Mead in 1720/21), then turning this situation into a “scandal” becomes all the easier. However, Krischer also points out that the “space” in which “lies and fake news” and conspiracy theories can “resonate” in the population soon diminished in both cases. “Epidemics are stress tests for societies and can reinforce certain discursive patterns”.