“Half of the people of Turkish origin do not feel recognised”

Emnid survey among people of Turkish origin in Germany: high sense of well-being, but widespread feeling of poor social recognition – vehement defence of Islam – fundamentalist attitudes common – cultural self-assertion particularly in the second and third generations of immigrants – Münster University’s Cluster of Excellence undertakes one of the as yet most comprehensive surveys among people of Turkish origin about integration and religiousness

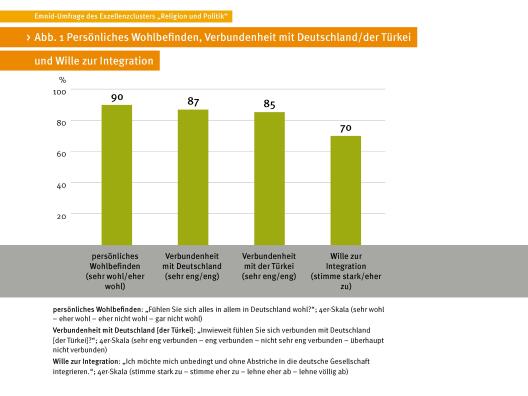

According to a representative Emnid survey, 90 per cent of people of Turkish origin in Germany enjoy living in the country, but more than half of them do not feel they are socially recognised. “The picture of the personal living conditions of the people of Turkish origin who live in Germany is more positive than could be expected, given the predominant state of discussion about integration”, said the head of the study “Integration and Religion as seen by People of Turkish Origin in Germany” of Münster University’s Cluster of Excellence “Religion and Politics”, sociologist of religion Prof. Dr. Detlef Pollack in Berlin on Thursday. Likewise, feelings of being disadvantaged are not more widespread among people of Turkish origin than in Germany’s total population. About half of respondents holds the view that they get their fair share compared to how others live in Germany. The number of the Germans who say this of themselves in West Germany is no higher than that and it is even lower in East Germany.

“However, people of Turkish origin who live in Germany lack the feeling of being welcome, of being recognised”, explains the head of the study. More than half of immigrants from Turkey and their descendants feel they are second-class citizens, no matter how hard they try to belong. For the representative survey, which is one of the most comprehensive surveys among people of Turkish origin about integration and religiousness, the research agency TNS Emnid interviewed some 1,200 immigrants from Turkey and their descendants 16 years of age and older on behalf of the Cluster of Excellence. Respondents of the first generation have been living in Germany for an average of 31 years. 40 per cent of respondents were born in Germany.

Vehement defence of Islam

The lack of social recognition is associated with a partially vehement defence of Islam, according to the head of the study. In sharp contrast to the attitude of the majority society, people of Turkish origin mostly ascribe positive attributes to Islam such as solidarity, tolerance and peaceableness. 83 per cent of immigrants and their descendants say that it infuriates them when Muslims are the first suspects after a terror attack. Three quarters advocate a prohibition of books and films that offend the feelings of profoundly religious people. Two thirds of respondents believe that Islam actually does fit in with the Western world, while 73 per cent of the population as a whole in Germany believe the opposite.

“The problems of integration can obviously be found, to a large extent, on the level of perception and recognition. As important as it is that the immigrants have a home and work, it is just as important that they are appreciated by society. From the point of view of the Muslim minority, Islam is a religion under attack that needs to be protected from harm, prejudice and suspicions”, according to Prof. Pollack.

Islamic fundamentalist attitudes common

At the same time, the survey results reveal a considerable share of Islamic fundamentalist attitudes that are rather inconsistent with the principles of modern societies, the sociologist explained. Half of the respondents agree with the statement “There is only one true religion.” 47 per cent consider it more important to follow the commandments of Islam than the German laws. One third believes that Muslims should return to the social order from the days of Prophet Muhammad. 36 per cent are convinced that only Islam is capable of solving the problems of our times. Prof. Pollack emphasises that the share of those who have a consolidated fundamentalist world view amounts after all to 13 per cent.

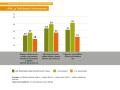

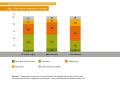

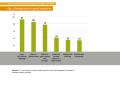

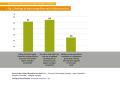

Figures of the study

© Exzellenzcluster "Religion und Politik"

© Exzellenzcluster "Religion und Politik"

© Exzellenzcluster "Religion und Politik"

© Exzellenzcluster "Religion und Politik"

© Exzellenzcluster "Religion und Politik"

© Exzellenzcluster "Religion und Politik"

© Exzellenzcluster "Religion und Politik"

© Exzellenzcluster "Religion und Politik"

© Exzellenzcluster "Religion und Politik"

© Exzellenzcluster "Religion und Politik"

© Exzellenzcluster "Religion und Politik"

© Exzellenzcluster "Religion und Politik"

© Exzellenzcluster "Religion und Politik"

© Exzellenzcluster "Religion und Politik"

© Exzellenzcluster "Religion und Politik"

© Exzellenzcluster "Religion und Politik"

© Exzellenzcluster "Religion und Politik"

© Exzellenzcluster "Religion und Politik"

© Exzellenzcluster "Religion und Politik"

© Exzellenzcluster "Religion und Politik"

© Exzellenzcluster "Religion und Politik"

© Exzellenzcluster "Religion und Politik"

© Exzellenzcluster "Religion und Politik"

© Exzellenzcluster "Religion und Politik"

© Exzellenzcluster "Religion und Politik"

© Exzellenzcluster "Religion und Politik"

© Exzellenzcluster "Religion und Politik"

© Exzellenzcluster "Religion und Politik"

© Exzellenzcluster "Religion und Politik"

© Exzellenzcluster "Religion und Politik"

© Exzellenzcluster "Religion und Politik"

© Exzellenzcluster "Religion und Politik"

© Exzellenzcluster "Religion und Politik"

© Exzellenzcluster "Religion und Politik"

However, the team of researchers headed by the sociologist sees considerable differences between the first generation, that is, those who immigrated to Germany as adults, and the second and third generations, that is, those who were born in Germany or immigrated as children. The share of those with a fundamentalist world view amounts to 18 per cent in the first generation but only to 9 per cent in the second and third generations. Likewise, more respondents of the first generation are very deeply religious: while 27 per cent of them believe that Muslims should not shake hands with people of the opposite sex, it is 18 per cent of the second and third generations who think so. Of the first generation, 39 per cent believe that women should wear headscarves, while 27 per cent of the following generation thinks the same. The percentage of Muslim women who actually wear headscarves has dropped from 41 to 21 per cent as well.

“Consequently, the popularity of fundamentalist attitudes might decrease further in future, if the integration of the younger immigrant generation continues to go well”, according to Prof. Pollack. The most important influencing factors against fundamentalist attitudes that emerge from the study are frequent contact with the majority society, a good command of German and integration into the labour market. Prejudicial factors are contact that is largely restricted to the Muslim community and the widespread feeling of a lack in recognition.

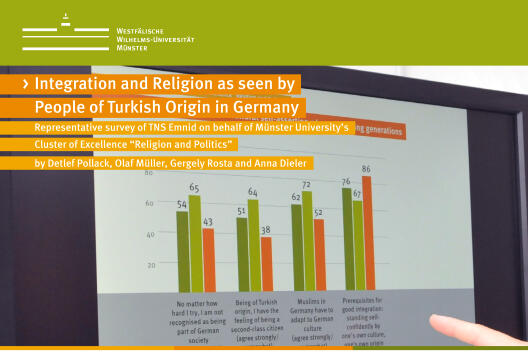

Second and third generations better integrated, but insist more strongly on self-assertion

At 43 per cent, second-generation and third-generation people of Turkish origin feel less rejected by the majority society than the first generation at 65 per cent, according to the survey. Furthermore, members of the second and third generations are better integrated in many aspects, as the increase in school-leaving qualifications, in knowledge of German and in contact with Germans illustrate. “However, the second and third generations insist more strongly on cultural self-assertion than the first generation”, says the sociologist. 72 per cent of the older generation and 52 per cent of the younger generation believe that Muslims should adapt to the German culture. 86 per cent of the second and third generations, but only 67 of the first generation think that one should stand self-confidently by one’s own origin.

“Although those who were born in Germany or who immigrated as a child are better integrated, the pendulum swings more towards self-assertion in their case than it does in the case of those who came as adults”, says the researcher. This can be explained by a distancing of the younger people from the older people and by higher demands regarding education and lifestyle.

“Both sides need to change their attitude”

“It is strongly recommended that politics and the civil society encourage more contact between Muslims and non-Muslims”, emphasises the scholar. “Be it in sports clubs, schools, educational institutions, church or mosque communities: they should meet, engage in common activities, discuss free of prejudice or celebrate. Signals of a lack in respect and refused recognition are to be avoided.”

“Both sides are needed”, says Prof. Pollack. “The German majority should have greater understanding for the strained situation of people of Turkish origin – caught between the conditioning by their background and adaptation.” They should appreciate in a differentiated manner that the majority of immigrants has no fundamentalist attitude. People of Turkish origin, on the other hand, should not simply react indignantly at reservations but also deal critically with the fundamentalist tendencies in their ranks, which are encountered nonetheless. (vvm)