In a place far from the world: the protective measure of quarantine

By literary scholar Pia Claudia Doering (Romance studies)

Quarantine is one of the key measures used to combat the corona pandemic. Imposing spatial isolation over a specific temporal period, it involves the categories of space and time. The word ‘quarantine’ accentuates the temporal dimension: entering German from French (hence the pronunciation of the anlaut as k), it goes back via intermediate stages to the Latin word quadraginta (‘forty’). Medieval medicine saw the period of 40 days as the border separating acute from chronic forms of illness. This specific period can be traced back on the one hand to the writings of the Greek physician Hippocrates, who identified 40 days as the usual turning-point in the course of an illness. On the other, it can have a religious origin, as the number ‘40’ has great symbolic power in Christianity. It represents in both the Old and the New Testament a period of penance and reflection as a prerequisite for a new beginning. When, after the Flood that lasted 40 days and 40 nights, the mountains slowly rose again from the water, Noah waited another 40 days before opening the window of the ark to let the raven fly out. After Jonah’s sermon, the city of Nineveh had 40 days to repent of their sins. Noah stayed 40 days on Mount Sinai to receive God’s Commandments. And Jesus also spent 40 days in the desert before setting out to preach God’s gospel.

Quarantine as a means to protect against the spread of epidemics was an invention of the flourishing medieval port cities at the time of the Great Plague. In 1377, the council of the Venetian trading colony of Ragusa (today’s Dubrovnik) ordered that all ships arriving from a plague-infected area drop anchor on a rocky island offshore, where the sailors and merchants had to quarantine themselves for a month. The inhabitants of Ragusa were forbidden to visit them, those who did so also being banished to the island for a month. Quarantine was initially for 30 days, but was soon increased to 40. There is evidence, for example, that the port of Marseille imposed a 40-day quarantine in 1383.

Quarantine in the port cities had enormous economic advantages: unlike port closures, it made trade and the turnover of goods still possible. Over time, the spatial isolation of travellers and goods arriving from affected areas was organized increasingly efficiently. Until the 17th century, quarantine stations were built on offshore islands or outside city walls. Particularly well-known besides the lazarettos of Dubrovnik is the Lazzaretto Nuovo, situated in the Venetian Lagoon, where goods were temporarily stored and disinfected in the main building, the 100-metre-long Tezon Grande. Inscriptions, drawings, seals, and symbols on the walls testify to the presence of merchants from all over the Mediterranean.

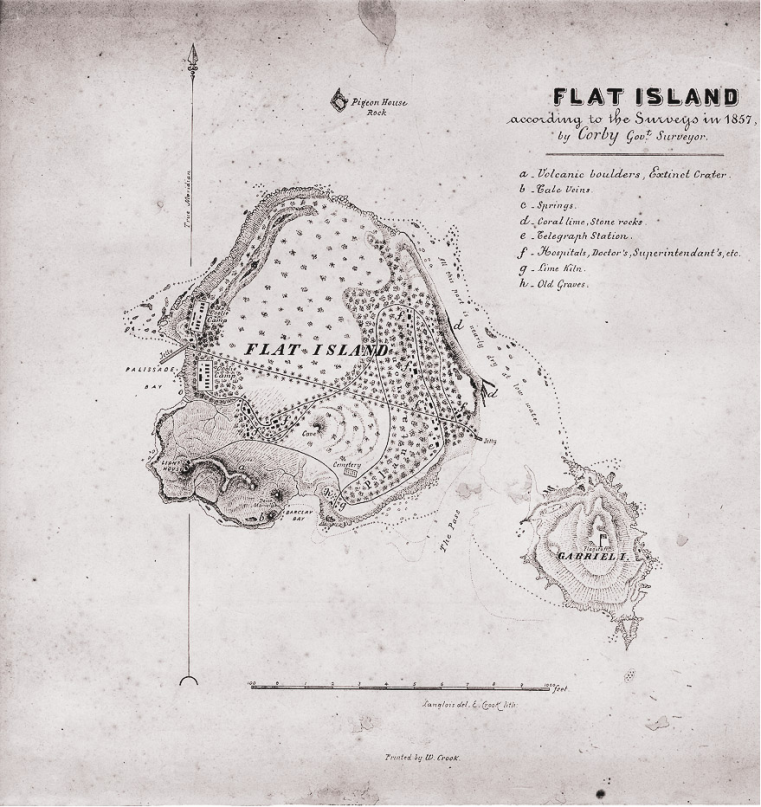

Literary works have come to focus on the exceptional situation of quarantine and its effects on individuals and social communities. José Saramago vividly describes the consequences of isolating people in an empty psychiatric institution in his 1995 novel Blindness (see Martina Wagner-Egelhaaf’s contribution in this dossier). The Quarantine, a novel by the French Nobel Prize winner for literature J.M.G. Le Clézio that was also published in 1995, is about how travellers – Europeans and Indian coolies – are prevented from going ashore at their destination of Mauritius because smallpox has broken out on their ship. The passengers are accommodated on the nearby Ile Plate (Flat Island, see illustration), which is inhabited by Indians. Soon, tensions break out between the different social and ethnic groups. The spatial and temporal seclusion of quarantine allows the author to explore the violent mechanisms of community and exclusion. Only the young Léon, who bears the same name as the novel’s narrator (who narrates from a later time perspective), experiences the island and the expanse of the sea as liberating. He finds happiness in his love for the mestizo Suryavati. When quarantine is over after 42 days and the travellers are finally allowed to board a ship to Mauritius, Léon and Suryavati have disappeared without trace. Refusing to live in the island colony of Mauritius or to return to France, Léon thus bears the name “Léon, le Disparu” in the family from then on and for generations to come.