The global spread of Jamaican Creole: The sociolinguistics of globalization and the sociolinguistics of performance

Jamaican Creole is the local vernacular of Jamaica and coexists with the island’s emerging local standard variety, Jamaican English. Jamaican Creole has increasingly become a symbol of national identity after the island’s independence in 1962 but a conservative linguistic ideology which discriminates Jamaican Creole as inferior to English has been retained. Despite persisting efforts by Jamaican linguists to enhance the de jure status of Jamaican Creole, English remains the sole official language of Jamaica. However, in his World System of Englishes Mair (2013: 262-265) postulates that Jamaican Creole has become globally relevant as a super-central variety while the importance of Jamaican English is regionally confined to the Caribbean. Most studies on the global spread of Jamaican Creole have focused on language use by native speakers in diaspora communities like London (Sebba 1993) or Toronto (Hinrichs 2011). In their Cyber-Creole research project Mair and his colleagues extent this scope to the use of Jamaican Creole in globalized computer mediated communication (e.g. Moll 2015). However, the main driving force behind the global spread of Jamaican Creole beyond Jamaican diaspora communities and online fora is the international success of Jamaican reggae and dancehall music. Most studies on the globalization of reggae and dancehall have taken a cultural studies perspective (e.g. Alleyne 2008; Cooper 2004) while there are hardly any sociolinguistic investigations of the transnational impact or appropriation of popular Jamaican music (e.g. Winer 1990).

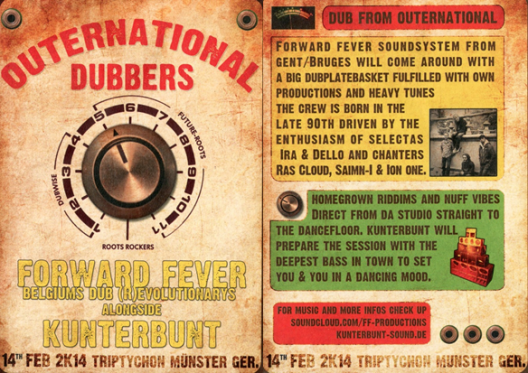

This project investigates the global spread of Jamaican Creole by analyzing its appropriation in specific reggae and dancehall contexts by non-native speakers from different European speech communities. The project follows Pennycook’s (2007: 58-77) performative agenda by focusing on the performance of Jamaican Creole on the basis of a constructionist approach to language and identity. While Pennycook mainly focusses on rap lyrics to analyze the transnational linguistic flows of Hip Hop, this study advances a contextualized analysis by taking into account the actual speech performance as well as the immediate context (e.g. the space or the audience’s perception of the performance). I analyze the performance of internationally successful European reggae artists in music videos, live performances, interviews, or documentaries. Artists include Gentleman from Germany, Alborosie from Italy, Soom T from Scotland and Stand High Patrol from France. Furthermore, the appropriation of Jamaican Creole by non-native speakers is studied in two German online reggae radio shows: Scampylama’s Serendiptiy Selection (https://soundcloud.com/scampylama) and Jugglerz Dancehall Radio (http://www.jugglerz.de). The project also includes ethnographic investigations of dub, reggae, and dancehall events organized by different local soundsystems in Münster, Germany.

This project aims to show how locally stigmatized vernaculars are spread worldwide mainly through subcultures “from below” in very different ways than prestige varieties, which are transported transnationally “from above” (Preisler 1999: 241) through education or the global capitalist market economy. As Jamaican Creole is spread globally in reggae and dancehall subculture it is often reduced from a fully functional language to a stylistic resource of the performance of a reggae or dancehall identity. Cultural appropriation is shown to be a main driving force for the global spread of Jamaican Creole: the appropriation of Jamaican Creole by non-native speakers in reggae and dancehall performances is often caught in between simplification, exploitation, and homage. On a theoretical level, this project adds a more context sensitive approach to Pennycook’s (2007) performative agenda and calls for a combination of the sociolinguistics of globalization with the sociolinguistics of performance.

References

- Alleyne, Mike. 2008. Globalization and commercialization of Caribbean music. Popular Music History 3 (3), 247-273.

- Cooper, Carolyn. 2004. Sound clash: Jamaican dancehall culture at large. New York: Palgrave.

- Hinrichs, Lars. 2011. The sociolinguistics of diaspora. Language in the Jamaican Canadian community. Texas Linguistics Forum 54, 1-22.

- Mair, Christian. 2013. The World System of Englishes. English World-Wide 34 (3), 253-278.

- Moll, Andrea. 2015. Jamaican Creole goes web: Sociolinguistic styling and authenticity in a digital ‘yaad.’ Amsterdam: Benjamins.

- Pennycook, Alastair. 2007. Global Englishes and transcultural flows. London: Routledge.

- Preisler, B. (1999). Functions and forms of English in a European EFL country. In Tony Bex & Richard J. Watts (eds.), Standard English: The widening debate, pp.237–267. London: Routledge.

- Sebba, Mark. 1993. London Jamaican: Language systems in interaction. London: Longman.

- Winer, Lise. 1990. Intelligibility of reggae lyrics in North America. Dread ina Babylon. English World-Wide 11 (1), 33-58.