2. Work in Progress

Dying to save the City in Athens and Boeotia

Postdoctoral Research

Ioannis MITSIOS (National and Kapodistrian University of Athens)

Dying a glorious death in battle is one of the main prerequisites of heroization for men. Achilles, in his characteristic monologue in the Iliad (9.410-6), chooses a short but glorious life, instead of a long inglorious one, gaining kleos and hysterophemia by dying on the battlefield. But how can kleos and hysterophemia be gained by women, given that they are excluded from war? The self-sacrifice of a female, preferably virgin, for the salvation of the community, “unum pro multis dabitur caput” and the phenomenon of “dying for doing” is well attested in Athenian myth.[1] Notably, in Boeotia, and nowhere else, we come across the exact same motif of the voluntary self-sacrifice of the virgin for the salvation of the city. We will return to the Boeotian examples later, but first the Athenian examples will be offered.

These sacrificial heroines include: a) Aglauros, the daughter of king Kekrops, b) the daughters of king Erechtheus and queen Praxithea – also known as the Erechtheids and the Hyakinthids – and c) the daughters of king Leos – also known as the Leokorai.

Philochorus (FGrH 328 F 105) attests that during the war between the city of Athens and Eleusis, the oracle of Delphi declared that the city of Athens would be saved only if someone sacrificed herself. Then, the heroine Aglauros threw herself from the cliffs of the Acropolis, heroically sacrificing herself for the salvation of the city. Her brave act resulted in the foundation of a sanctuary, securely placed on the east slope of the Acropolis, thanks to an inscription – find in situ — by Dontas (FIG. 1).[2]

Lycurgus (Against Leocrates, 98-100) – citing Euripides’ fragmentary preserved tragedy “Erechtheus” – similarly attests that the Delphic oracle demanded that during the war between Athens and Thrace, the city of Athens would be saved only if queen Praxithea, wife of king Erechtheus, sacrificed her own daughters. Just like the case of Aglauros, the self-sacrifice of the daughters of Erechtheus resulted in the foundation of a sanctuary – known as the Hyakintheion (IG I2 1035.52) – although its location remains uncertain.[3] The Erechtheids/Hyakinthids have been identified with the dancing Hyades at the “Akanthus column”, in Delphi, although the identification is far from certain, as well as their relevance to Hyades (FIG. 2).[4]

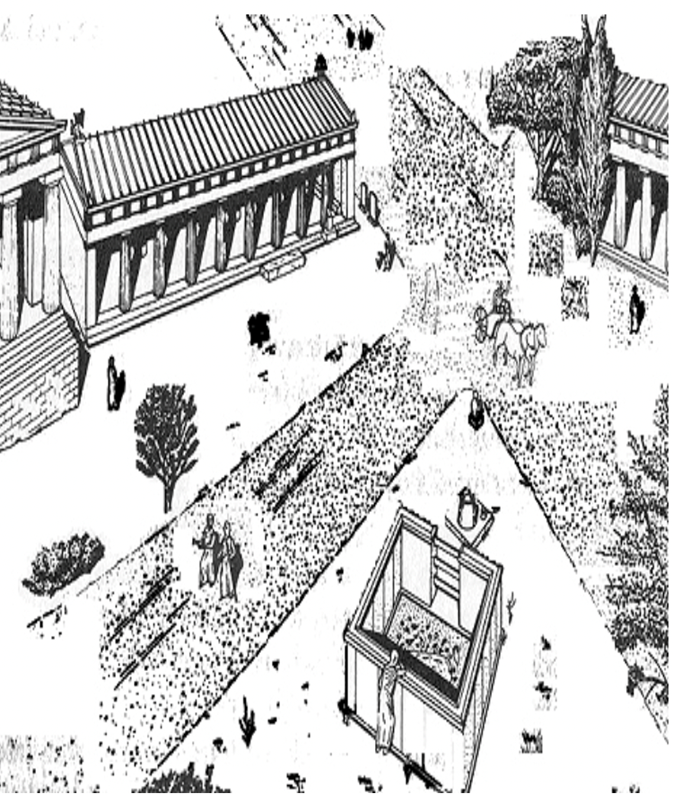

Demosthenes (60.29) is the first who speaks about the Leokorai, attesting that the daughters of the Athenian king Leos sacrificed themselves for the communal good. Just like Aglauros and the daughters of Erechtheus, the daughters of Leos were receiving cult – as attested in Thucydides (1.20) – but the exact location of the Leokoreion is debatable, although it is mostly recognized with the crossroads shrine in the Agora of Athens (FIG. 3).[5]

As already stated, in Boeotia we come across this identical mythological motif, where virgins voluntary sacrificed themselves for the salvation of the city. The Boeotian examples include: a) Metioche and Menippe, daughters of king Orion – also known as the Koronides – b) Androkleia and Alkis, daughters of Antipoenus – also known as the Antipoenides – and may have included, c) Henioche and Pyrra, daughters of king Kreon and d) the daughters of king Skedasos.

Antoninus Liberalis (Metamorphoses 25) attests that when the city of Aionia was suffering from plague, the daughters of Orion, Metioche and Menippe consulted the oracle of Apollo Gortynius and received the response that the city will be saved only if they sacrificed themselves. Then, Metioche and Menippe committed suicide for the salvation of the city.

Pausanias (9.17.1) similarly attests that Androkleia and Alkis, daughters of king Antipoenus, willingly sacrificed themselves (in place of their father) in order to obtain victory in the war between the Thebans and the Orchomenians. Just like several heroines, their brave act resulted in the foundation of a sanctuary, located in the precinct of Artemis Eukleia.

The last two examples of Boeotian sacrificial heroines, may have included the daughters of king Skedasos at Leuktra and the daughters of king Kreon at Thebes.[6]

Phanodemus (FGrH 325 F4) – referring to the self-sacrifice of the daughters of Erechtheus – relates it with the war between Athens and Boeotia, instead of Thrace. This testimony – as well as the fact that the mythological pattern of suicidal virgins applies exclusively in Athens and Boeotia – suggests an interaction between the cities.

Given the striking similarities in the mythological tradition of sacrificial virgins between the cities of Athens and Boeotia and by employing a holistic approach – taking into consideration the literary, epigraphic, iconographic and topographic evidence – my upcoming research will examine the self-sacrifice of Athenian and Boeotian heroines during times of plague, famine and war.

[1] For the motif of virgin sacrifice for the salvation of the city see: Kearns 1989, 57-63; 1990, 330-31; Wilkins 1990, 186-87; Larson 1995, 101-04; Lefkowitz 1995, 35- 37; Kron 1999, 78-83; Mitsios 2022; 2024.

[2] Dontas 1983.

[3] On the location of the Hyakintheion, see Kearns 1989, 102; Frame 2009, 449; Connelly 2014, 232-33.

[4] Delphi 1584. Ferrari 2008, 146-47 identifies the daughters of Erechtheus with the dancing females on the “Akanthus column” in Delphi. On the complicated (and problematic) identification of the Erechtheus/Hyakinthids with the Hyades, see, Collard, Cropp and Lee 1993, 194; Gantz 1993, 128; Kearns, 1989, 61-62; Connelly 2014, 244; Sourvinou-Inwood 2011, 123-34; Mitsios 2024,16-18.

[5] On the location of the Leokoreion, see Thompson and Wycherley 1972, 121-23; Shear 1973a, 126-34; 1973b, 360-69; Thompson 1978, 96-102; 1981, 343-55; Camp 1986, 78-79; Mitsios 2022, 88-89.

[6] Schachter 1972, 19-20.

Bibliography

Camp, J. 1986. The Athenian Agora: excavations in the heart of classical Athens. London.

Collard, Christopher, M. J. Cropp and K. H. Lee. 1993. Euripides: Selected Fragmentary plays. Warminster.

Connelly, J. B. 2014. The Parthenon Enigma. New York.

Dontas, G. 1983. “The True Aglaurion.” Hesperia 52: 48–63.

Ferrari, G. 2008. Alcman and the Cosmos of Sparta. Chicago.

Frame, D. 2009. Hippota Nestor. Washington, DC/Cambridge.

Gantz, T. 1993. Early Greek Myth: A guide to Literary and Artistic Sources. Baltimore.

Kearns, E. 1989. The heroes of Attica. London.

Kearns, E. 1990. “Saving the City.” In O. Murray and S. Price (eds.), The Greek City: From Homer to Alexander. Oxford: 323–44.

Kron, U. 1999. “Patriotic Heroes.” In R. Hägg (ed.), Ancient Greek hero cult. Stockholm: 61–83.

Larson, J. 1995. Greek heroine cults, Madison.

Mitsios, I. 2022. “Ancient Pandemics in mythical Athens.” Interface 17: 85–108.

Mitsios, I. 2024. “Mythical Athenian heroines in times of war.” In G. Wrightson (ed.), Ancient Warfare. Cambridge: 7–23.

Lefkowitz, M. R. 1995. “The Last Hours of the Parthenos.” In E. Reeder (ed.), Pandora: Women in Classical Greece. Princeton: 32–37.

Schachter, A. 1972. Teiresias 2: 19–20.

Shear, T. L. 1973a. “The Athenian Agora Excavations of

1971.” Hesperia 42: 121–79.

Shear, 1973b. “The Athenian Agora Excavations of 1972.”

Hesperia 42: 359–407.

Sourvinou-Inwood, C. 2011. Athenian Myths and Festivals: Aglauros, Erechtheus, Plynteria, Panathenaia, Dionysia. Oxford.

Thompson, H. A. 1978. “Some Hero Shrines in Early Athens.” In W. A. P. Childs (ed.), Athens Comes of Age: from Solon to Salamis. Princeton: 96–108.

Thompson, H. A. 1981. “Athens Faces Adversity.” Hesperia 50: 343–55.

Thompson, H. A. and R. E. Wycherley. 1972. The Agora of Athens: the history, shape and uses of an ancient city center. Princeton.

Wilkins, J. 1990. “The State and the Individual: Euripides’ Plays of voluntary self-Sacrifice.” In A. Powell (ed.), Euripides, Women and Sexuality. London: 177-194.