A Find of a Bosporan Coin at Trębaczów, site 2, Kazimierza Wielka district (Poland)

Zusammenfassung: Der

Artikel widmet sich einer Bronzemünze von Sauromates II., dem

Herrscher des Bosporanischen Königreichs (174/175–210/211 n.

Chr.). Das Stück wurde bei einer archäologischen Untersuchung

der Siedlung Trębaczów (Fundstelle 2), Kazimierza Wielka Poviat,

entdeckt, die in die Zeit der Przeworsk-Kultur datiert. Vom

Nominal als »Dreifach Sestertius« oder »Drachme« angesprochen,

gehört die Prägung zu den zwei Serien von Bronzemünzen, die in

die Zeit um 186–196 n. Chr. (Zograf 1951; Frolova 1997a) oder in

die Jahre um 180–192 n. Chr. (Anokhin 1986) datiert werden.

Der neu entdeckte Fund erweitert eine kleine Gruppe

bosporanischer Münzen, die zwischen der zweiten Hälfte des 1.

Jahrhunderts v. Chr. und dem 4. Jahrhundert n. Chr. geprägt und

auf dem Gebiet des heutigen Polen entdeckt wurden. Bisher waren

sechs derartige Funde bekannt. Das neue Exemplar fand

wahrscheinlich in der ersten Hälfte oder in den ersten Jahren

der zweiten Hälfte des dritten Jahrhunderts n. Chr. durch

Kontakte zwischen verschiedenen Bevölkerungsgruppen im ost- und

mitteleuropäischen Barbaricum den Weg zur Siedlung der

Przeworsk-Kultur.

Coins minted by the rulers

of the Bosporan Kingdom issued from the second half of the 1st

century BC until the first half of the 4th century AD are

relatively rare finds in the areas of the Roman-period Przeworsk

and Wielbark cultures[1].

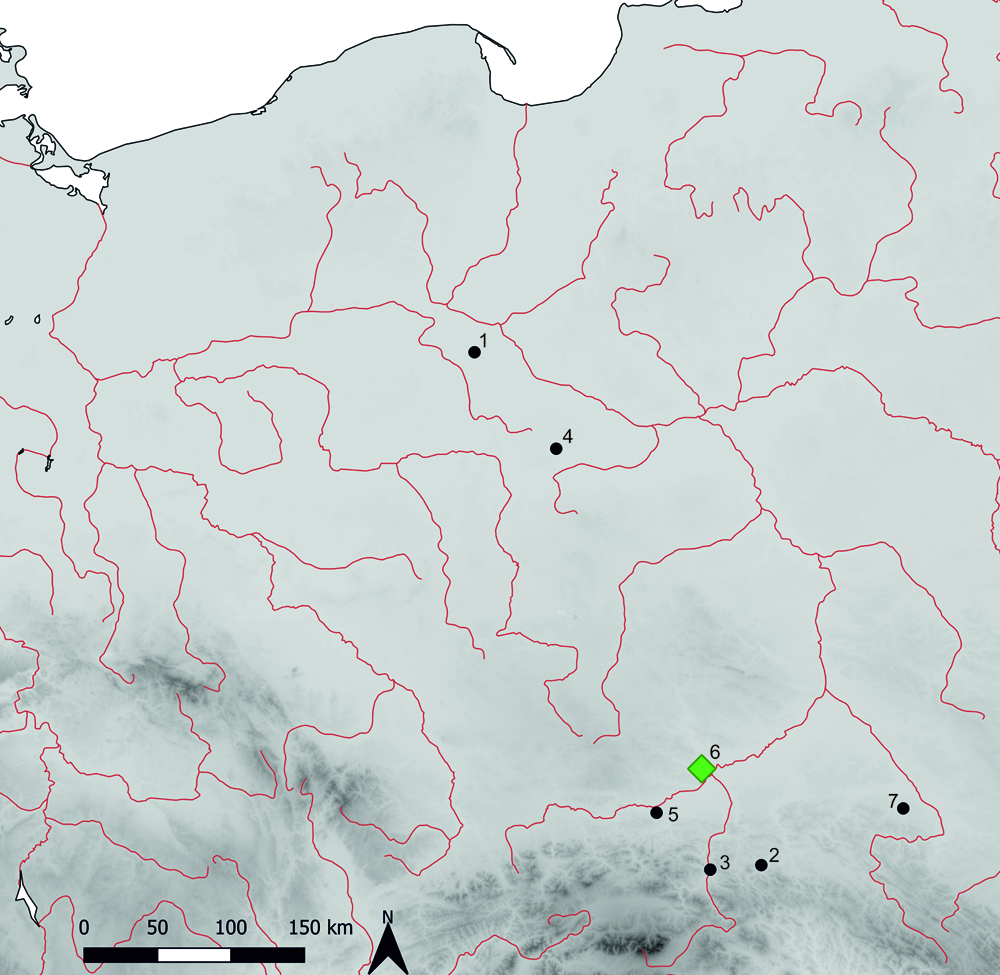

Previously, six such finds had been recorded in the area of

present-day Poland, including four in the region historically

known as Lesser Poland, and two in Central Poland: one each in

Mazovia and Kujavia (table 1; map 1)[2].

It should be noted that only the last two discoveries have been

made in recent years, since the use of metal detectors has

become widespread. All the Lesser Poland finds were recorded in

the second half of the 19th century and in the first half of the

20th century. Therefore, each new discovery of a Bosporan coin

is of great importance, not only because of the addition to

range of source material, but because it confirms the older

finds, and is particularly valuable in cases where these remain

doubtful.

Map 1: Finds of Bosporan Coins in Poland: 1 – Gąski, Inowrocław District, Kuyavian-Pomeranian Voivodeship; 2 – Gorlice - Glinik Mariampolski, Lesser Poland Voivodeship; 3 – Nowy Sącz-Zabełcze, Lesser Poland Voivodeship; 4 – Skłóty, Kutno District, Łódź Voivodeship; 5 – Staniątki, Wieliczka District, Lesser Poland Voivodeship; 6 – Trębaczów, Kazimierza Wielka District, Świętokrzyskie Voivodeship; 7 – Zarzecze, Przeworsk District, Subcarpathian Voivodeship. Drawing by Jan Bulas

Recently, a new, seventh

find of a Bosporan coin was registered in western Małopolska in

Trębaczów, commune of Opatowiec, Kazimierza Wielka district (map

1). The discovery was made in March 2020 during a surface

prospection, carried out with a metal detector in a Roman period

settlement by a team of archaeologists from the Arch Foundation[3].

The research, conducted on the basis of permit No. 3493/219

issued by the Provincial Conservation Office in Kielce, is part

of the »Ekspedycja Rzemienowice« (Rzemienowice Expedition)

project, focused on the study of sites from the Roman period in

the valley of the Młyńska stream, a tributary on the left bank

of the River Vistula. Annual surface prospecting, analysis of

satellite images, and aerial prospecting have led to the

discovery of many settlements of the Przeworsk culture in this

area. Numerous Roman imports have been discovered in all the

researched sites, mainly coins and brooches. This pattern

corresponds with the finds from the famous settlement (site 2)

in Jakuszowice, located 8.5 km as the crow flies from Trębaczów[4].

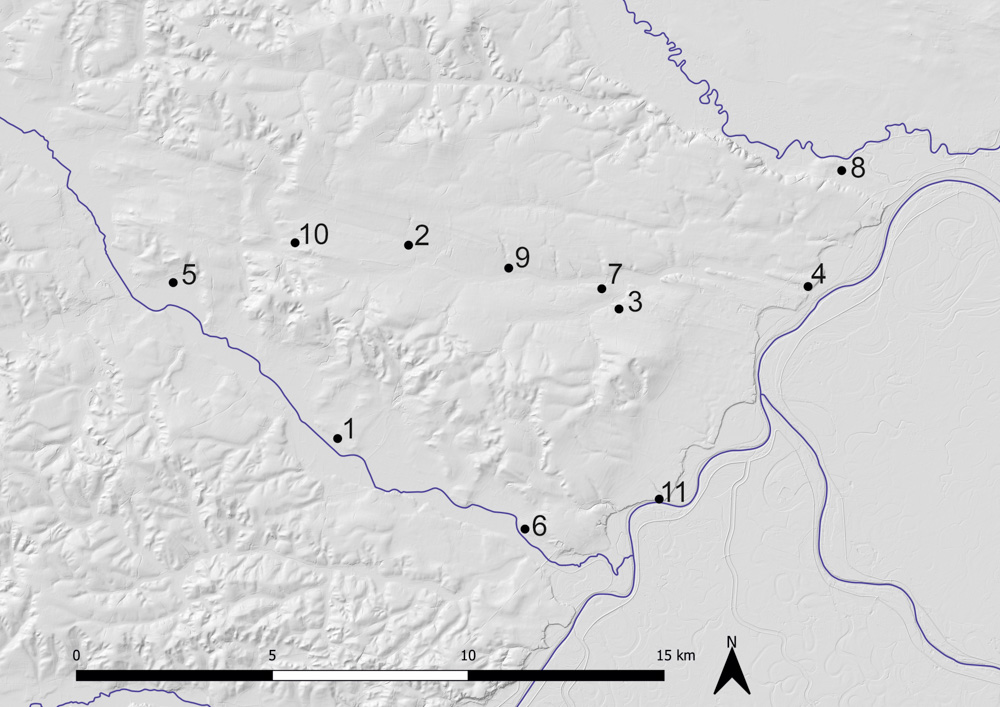

The aforementioned Młyńska valley is located between the valleys

of two much larger tributaries on the left bank of the Vistula,

the Nida and Nidzica rivers. The position of the Młyńska stream

and the settlements on it had undoubted advantages, among them

its location on the extension of one of the most important

routes leading from the south to the north, along the River

Dunajec. This area was undoubtedly part of an important nexus of

cultural and commercial contacts. It should be added that in the

same microregion there are other excavated sites where Roman

coins have been discovered (including Bejsce and Zagórzyce)[5],

and places where accidental discoveries of such items have been

recorded (Chwalibogowice, Stary Korczyn, Uściszowice, Wyszogród)[6].

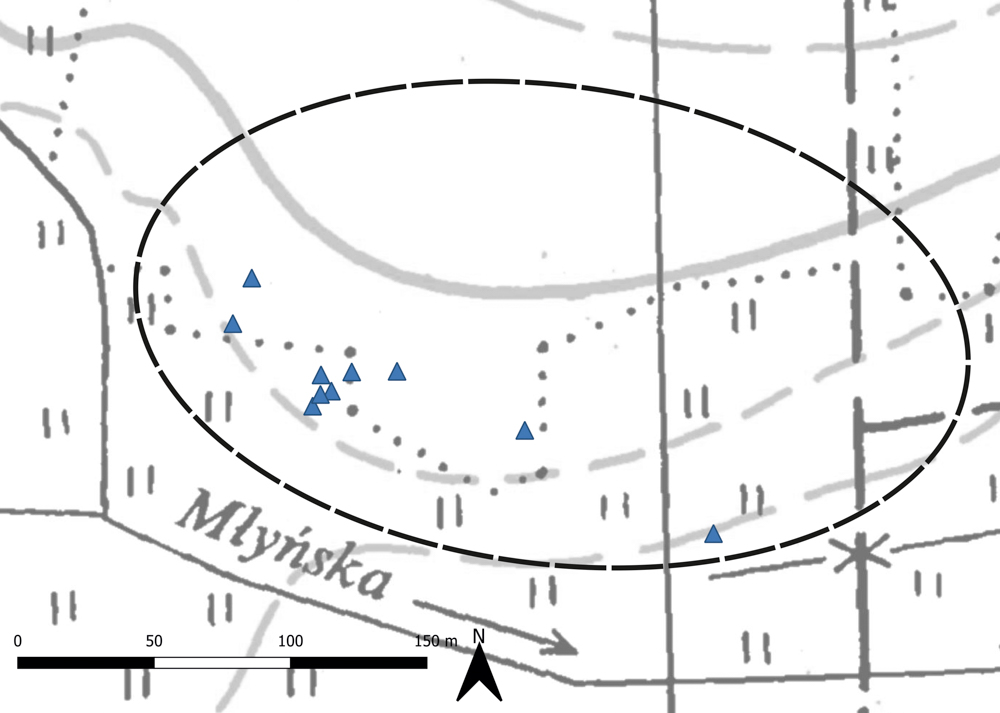

Site no. 2 in Trębaczów was

discovered in 2017 as a result of analysis of satellite images

and vertical aerial photos taken with an unmanned aerial vehicle

(a so-called drone), which revealed the presence of

characteristic vegetation anomalies correlating with the remains

of sunken or excavated structures typical of the Przeworsk

culture settlements. These observations were confirmed in 2018

during surface surveys. The settlement in question is situated

on a gentle slope in a slightly elevated position above the

river valley. During the research, a large amount of ceramic

material was registered, including hand-made fragments of

Roman-period phase B pottery and Roman-period phase C pottery

made on a potter’s wheel. Finds of metal objects allow for a

more precise determination of the functioning of the settlement

between phase B1 (beginning of the 1st century AD) and at least

the end of phase C1 (around the middle of the 3rd century AD).

In addition to the aforementioned Bosporan coin, ten other Roman

coins were found at the site. These are denarii, including one

republican, and nine imperial specimens from the 1st–2nd century

AD (map 2). The oldest coin is the republican denarius,

an issue of Q. Titus, minted in 90 BC (RRC

341/1), and the youngest is a denarius of Commodus

from AD 187–188 (RIC

III 162 or

167)[7].

It should be added that in Trębaczów there is another settlement

(site 1), located about 400 meters in a straight line

from site 2, where also during surface prospecting one denarius

was discovered, minted during the reign of Nerva.

The Bosporan coin from site

2 was found in the form of a corroded and completely shapeless

metal lump, and was thus originally included in the group of

insignificant ›junk‹ finds[8].

As a result, exact data relating to the place and time of the

discovery were not recorded. Only later, careful inspection of

the material and the conservation undertaken resulted in the

cleaning of the object and its proper identification.

Nevertheless, the precise location of the discovery spot, and

thus the detailed context of the find and its possible

relationship with other coins discovered at site 2 are not

clear.

The specimen found in

Trębaczów was minted in the name of Sauromates II

(174/175–210/211), the king ruling at the turn of the 2nd and

3rd centuries AD (fig. 1); for a similar, better

preserved piece cf. fig. 2). During his long reign, the

ruler minted copious issues. The coin in question belongs to a

series of large bronzes with a portrait of the ruler and the

royal title on the obverse, and an eagle and the denominational

mark (PMΔ = 144 units) on the reverse. According to the

classifications of Aleksandr N. Zograph and Nina A. Frolova,

such coins belong to Sauromates II’s second series of bronze

coinage and were minted in the years AD 180–196[9].

Vladilen A. Anokhin also includes the type in question in the

second series of bronze coins of this ruler, although he dates

it to the reign of the Roman Emperor Commodus (180–192)[10].

The researchers have defined the denomination of the issue as a

triple sestertius, equal to ¾ of one denarius (Zograph,

Anokhin), or as a drachm (Frolova).

Cimmerian Bosporus

Sauromates II (174/175–210/211)

AE, denomination PMΔ

Obv. Diademed and draped bust of Sauromates; r.; ΒΑCΙΛΕWC CΑYΡΟΜΑΤΟΥ; dotted border

Rev. Eagle standing l., head turned back, with wreath in beak; [PMΔ]; dotted border

11.88 g; 29.4 mm; 12 h

Cf. Frolova 1997a, Pl. XCI, 17; Anokhin 1986, 165 no. 618a, Pl. 29; RPC IV Temp. No. 3879

The National Museum in Krakow; Donation of Lech Kokociński; Inv. No. MNK VII-A-6899

Photo courtesy of the National Museum in Krakow

Among the relatively

infrequent finds of Bosporan coins in Poland, no discoveries of

specimens minted by Sauromates II have been recorded so far (cf.

table 1)[11].

The closest chronologically to the coin from Trębaczów are the

middle bronze (›denarius‹) of his successor Rhescouporis III

(211/212–228/229) discovered in Staniątki, Wieliczka district (table

1, no. 5)[12]

and the so-called ›denarius‹ of Ininthimaeus (234/235–238/239)

found in Skłóty, Kutno district (table 1, no. 6)[13].

When analyzing the overall chronological structure of the finds

of Bosporan coins discovered in Poland, two groups can be

distinguished. One is made up of coins minted in the 1st century

AD, effectively consisting of issues from the second half of the

century: a bronze of Cotys I (45–68) found in Zarzecze,

Przeworsk district (table 1, no. 2)[14]

and a sestertius of Rhescouporis II (68/69–91/92), which is part

of the alleged hoard discovered in Glinik Mariampolski (now part

of Gorlice)[15].

The other group includes the aforementioned coins from the 1st

half of the 3rd century AD and the newly discovered coin of

Sauromates II. In addition to these groups, there is also a

small bronze of Polemon (15–9 BC) from the vicinity of Nowy Sącz

(table 1, no. 1), (Nowy Sącz-Zabełcze)[16]

and, due to the lack of a precise description, a large bronze

(sestertius) of an unspecified Bosporan ruler minted in the 1st

or 2nd/3rd century AD, found in Gąski, Inowrocław district (table

1, no. 7)[17].

In the latter case, the exact identification of the coin would

allow an attribution to the first or second group. It should be

noted, however, that the different chronological structure of

the groups of finds of Bosporan coins does not necessarily have

to be significant in the context of the chronology of their

influx into the area of today’s Poland (see below). What is

noteworthy, however, is the lack among Polish finds of Bosporan

coins minted in the second half of the 3rd and 4th century AD

(see below). Unless this is the result of the state of research,

the lack of these coins may be important for determining the

time of the influx of Bosporan coins into present-day Polish

territory[18].

The chronology of Bosporan

coins found in Poland is closely related to their denominational

structure (cf. table 1). The finds consist only of bronze

coins. Furthermore, apart from the coin from Nowy Sącz-Zabełcze

(table 1, no. 1), these are items that can be classified

as medium (›denarii‹) or large bronzes (sestertii, triple

sestertii/drachms) and therefore similar in size to large

imperial bronzes. This gives rise to a thesis that at least some

of these coins performed a similar function in the Barbaricum as

large imperial bronzes[19].

The latter are relatively rare in finds from the Przeworsk

culture area, compared to the finds of denarii or their

imitations. It is also worth recalling that so far no finds of

gold, electrum, silver or bronze Bosporan staters have been

registered in the area of today’s Poland.

All the finds of Bosporan

coins recorded in contemporary Poland so far come from the areas

covered by the settlement of the Przeworsk culture during the

Roman period. One can only perhaps consider whether in the case

of the find from Nowy Sącz-Zabełcze (table 1, no. 1),

based on the date of the influx of the Polemon coin, it should

not be associated with the Puchov culture. So far, we do not

know of such discoveries from the settlement area of the

Wielbark culture or the Masłomęcz group. It seems, however, that

this is an effect of the state of the research rather than a

reflection of the real situation. Recently, Dr.

Kirylo

Myzgin identified a find of a coin minted in Chersonesus,

possibly from the area of the Masłomęcz group, which

potentially confirms the presence of coins from the region of

the northern Black Sea shores in the territory of contemporary

Poland covered by Gothic settlement during the Roman period[20].

At the same time, it should

be emphasized that numerous finds of coins of the rulers of the

Bosporan Kingdom have been registered in today’s Ukraine and

Russia, mainly in the Cherniakhiv Culture area[21],

and also, less numerously, in today’s Moldova, Belarus, and

Lithuania[22].

With a small number of finds of such coins in the Roman Balkan

provinces and their practical lack in the territories of today’s

Slovakia, the Czech Republic and the eastern German Länder, the

eastern or south-eastern direction of their influx into today’s

Poland seems to be the most likely[23].

The Polish lands seem to constitute the western border of the

influx of coins of interest to us in the area of the European

Barbaricum. Several finds that form a cluster in the area of

today’s Saarland, Hessen, and Baden-Württemberg, i.e. the

western and south-western German Länder, should rather be

associated with a different historical and cultural context[24].

Among the various

hypotheses concerning the circumstances of the influx of

Bosporan coins into present-day Polish lands, the most probable

seems to be one that links them with internal Barbarian

interactions, primarily between the Sarmatians and/or people of

the Cherniakhiv, Wielbark and Przeworsk cultures[25].

This type of contact is certainly evidenced by non-numismatic

phenomena present in the archaeological material[26].

They intensify from the second half of the 2nd century AD. At

that time a clear movement of the Przeworsk and Wielbark Culture

population to the east and south-east occurred[27].

Those migrations are widely connected with movements of the

Vandals and the Goths which are recorded in the historical and

led to the significant changes in the cultural situation in

Central and Eastern European Barbaricum during the 3rd century

AD[28].

The nature of any contacts, however, remains unclear, at least

for the time being, and the question of whether they were

commercial, social, or political contacts remains open. Perhaps

they were of a complex and varied nature.

In their studies on finds

of Bosporan coins in the Cherniakhiv Culture area, Georgiy

Beidin and Myzgin distinguished among them three chronological

groups. The first consists of coins minted before the so-called

Gothic Wars, the second of issues struck during those wars, and

the third of coins minted after their conclusion[29].

As a consequence, they proposed a three-phase influx of Bosporan

coins, where the individual phases are represented by coins they

classified into the three groups mentioned above. Relating this

division to the finds from Poland (which it should once again be

emphasized were much less numerous) we can confirm that they are

made up of coins corresponding to the first and second groups of

Beidin and Myzgin. With the small sample of ›Polish‹ finds, it

is difficult, however, to assign precisely particular

discoveries to the first or second group, and thus to

differentiate the time of their influx according to the time of

their release[30].

In fact, perhaps, apart from the very early coin of Polemon,

allegedly discovered in Nowy Sącz-Zabełcze (table 1, no. 1),

it is difficult to place the influx of any Bosporan coin from a

›Polish‹ find into a period earlier than the 2nd half of the 2nd

century AD. In the case of the coins that we have classified in

the second chronological group, this is self-evident, because

they were minted in the last quarter of the 2nd century AD or

later. The coin of Rhescouporis II (68/69–91/92), which was

assumed to be part of the hoard found in Gorlice-Glinik

Mariampolski (table 1, no. 3), could have reached the

Polish Carpathians not earlier than around the middle of the 2nd

century AD, as indicated by the current dating of this deposit[31].

In fact, uncertainty remains only in the case of finds from

Zarzecze, Przeworsk district (table 1, no. 2) (the coin

of Cotys I (45–68) and Gąski, Inowrocław district (table 1,

no. 7) (an undefined king of the 1st, 2nd or 3rd century

AD). It seems, however, that in these cases there are also some

reasons not to exclude them from the influx in the second half

of the 2nd century AD, or even later. The coin from Zarzecze (table

1, no. 2) was discovered along with a coin minted in Ascalon

in the 1st or 2nd century AD[32].

As for the piece from Gąski (table 1, no. 7), it cannot

be ruled out that it was minted as early as the second half of

the 2nd or the beginning of the 3rd century AD. Therefore, it

seems that most of the Bosporan coins found their way to today’s

Poland in the second half of the 2nd or more probably in the 3rd

century AD.

Other monetary finds also

provide a point of reference for dating their influx.

Simplifying and briefly

describing the issue of the influx of Roman coins to the Central

European Barbaricum, we can summarize this problem as follows:

most Roman coins minted at imperial mints in the 1st and 2nd

centuries AD found their way to the present Polish lands in the

last decades of the 2nd and/or the beginning of the 3rd century

AD[33].

Some of them, however, could also have arrived even later, in

the next two centuries, as a result of the redistribution of the

pool of, mainly, denarii and, to a lesser extent, other coins in

the Barbarian environment comprising the populations of various

archaeological cultures (Przeworsk, Wielbark and Cherniakhiv

Cultures) identified in the area of Central and Eastern

European Barbaricum[34].

During the later phases of the 3rd century AD, denarii and

antoniniani of the 3rd century minted after the reign of

Septimius Severus, gold aurei and imperial AEs from the 1st–3rd

centuries AD, debased radiates from the 2nd half of the 3rd

century AD, as well as smaller numbers of subaerati and other

categories of counterfeits, copies and imitations of Roman coins[35].

Again, some of these objects, mainly the copies and imitations,

could have come to today’s Polish lands even later. Therefore,

even given that certain groups of coins – Greek, Roman

Republican issues and Celtic, and maybe even Dacian imitations –

found their way to the Central European Barbaricum earlier, it

is difficult to accept the thesis that the Bosporan coins

arrived before the main mass of Roman coins[36].

Again, a possible exception could be the coin of Polemon found

near Nowy Sącz-Zabełcze. Another interesting point of reference

for the chronology of the finds of Bosporan coins is the

chronological structure of coins minted in the Provincial mints

and found within the borders of modern Poland state[37].

Of course, bearing in mind

the various possible circumstances of the influx of the Roman

provincial coins found in Poland, it is important to note that

the vast majority of them were minted in the 3rd century AD,

during the reigns of the Severan dynasty or later. It can

therefore be assumed that it was during the third century AD

that the greatest influx of provincial coins into the territory

of contemporary Poland occurred[38].

This is confirmed by the broader perspective of finds from the

areas of the settlement of the Cherniakhiv Culture, where

numerous provincial coins were discovered, most of which were

minted in very similar periods to those most frequently

represented in Polish finds[39].

As already mentioned, the contacts among the Przeworsk, Wielbark

and Cherniakhiv cultures played an important role in the

redistribution of Roman coins.

Taking all this into

account, it can be hypothesized that the majority of Bosporan

coins found in Poland, regardless of the date of their minting,

arrived in the 3rd century AD, perhaps along with some

provincial coins and imitations of denarii from area of the

Cherniakhiv Culture[40].

This also applies to the coin found in Trębaczów (table 1,

no. 4) that is presented here. At the same time, it is

impossible to answer unequivocally the question whether the

influx of Bosporan coins was the result of events directly

related to the Gothic Wars, or whether a different, perhaps more

complex reason is behind it. On the other hand, these coins

could not have arrived in present-day Poland very late. The lack

of finds of Bosporan coins, mainly staters, minted in the 2nd

half of the 3rd and in the 4th century AD, seems to provide

indirect evidence for. It is true that their absence may be the

result of the state of research, but currently we do not know of

a single find of such a coin in Poland, althoug such finds are

recorded in the Cherniakhiv Culture area[41].

Adding to this the fact that so far the latest Bosporan coin

from Poland is a ›denarius‹ of Ininthimeus (234/235–238/239), we

can cautiously assume that the influx of Bosporan coins to the

Polish lands ended at the latest in the middle, or possibly in

the early years of the second half, of the 3rd century AD.

The find of the coin of

Sauromates II in Trębaczów (table 1, no. 4) is very

important for a further reason. It is the first discovery of a

Bosporan coin from Poland made during regular archaeological

research. Because of this, it confirms the influx of such coins

to Polish lands in the Roman period, and gives credibility to

other finds made accidentally or by so-called detectorists.

Although the coin does not have a strict archaeological context,

its connection with a Roman period settlement is indisputable.

It is therefore, like other so-called imports, including coins,

testimony to the interregional connections between the

settlement in Trębaczów, the microregion in which the settlement

was located, and the broader context of the western Małopolska

settlements inhabited during the Roman period by the people of

the Przeworsk culture. Furthermore, in this context, it is worth

mentioning the Roman provincial coins found in the famous

settlement in Jakuszowice, located, as mentioned, only 8.5 km

away (site 2)[42].

Together with other sorts of imports they proof links between

western Małopolska and other regions of Barbaricum and

Rome. The nature of these links has been not fully explained,

but regardless of whether they were direct or indirect contacts,

their interregional nature is not open to discussion.

|

No |

Reign |

Metal |

Denomination |

Dates |

Find spot |

References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1 |

Polemon (15–9) |

AE |

|

15–9 BC |

Nowy Sącz

–Zabełcze |

Frolova 1997a,

42, type III, Pl. XV, 15–16a |

|

2 |

Cotys I (45–68) |

AE |

|

AD 63–68 |

Zarzecze,

Przeworsk District |

Frolova 1997a, 10 f., Pl.

XIV, 7–10;

RPC I no. 1930 |

|

3 |

Rhescuporis II

(68/69–91/92) |

AE |

Sestertius |

AD 80–93 |

Gorlice-Glinik

Mariampolski |

Frolova 1997a, 105, 1st

group, Pl. XXXI, 4–15;

RPC II no. 469 |

|

4 |

Sauromates II

(174/175–210/211) |

AE |

Triple

sestertius |

AD 180–196 |

Trębaczów,

Kazimierza Wielka District |

Frolova 1997a, Pl. XCI,

17;

RPC IV Temp. No. 3879 |

|

5 |

Rhescuporis III

(211/212–228/229) |

AE |

›Denarius‹ |

AD 211–215 |

Staniątki,

Wieliczka District |

Frolova 1997b,

10 f., Pl. XIV, 7–10 |

|

6 |

Ininthimeus

(234/235–238/239) |

AE |

›Denarius‹ |

234/235–238/239 |

Skłóty, Kutno

District |

Frolova 1997b, 37, 232,

Pl. XXXVII, no. 13;

RPC VII,2 –(unassigned;

ID 3499) |

|

7 |

Undetermined

ruler |

AE |

Sestertius |

End of 1st to

beginning of the 3rd cent. AD |

Gąski,

Inowrocław District |

Cf. Frolova

1997a, Pls. XLIV–LXI |

[1]

The authors

would like to

express their profound thanks to

Dr. Kirylo

Myzgin and Dr. hab. Arkadiusz Dymowski from the

University of Warsaw for valuable comments and remarks

on this text and to Dr. Ulrich Werz and Claire Franklin

for making our English readable. At the same time, we

would like to emphasize that all errors and shortcomings

are borne solely by ourselves.

[2]

Bodzek – Madyda-Legutko 2018; Bodzek – Madyda-Legutko

2013; Bodzek – Jellonek – Zając 2019, 60–62.

[3]

The research is

conducted by Jan Bulas, MA, Michał Kasiński PhD, an

employee of the Jagiellonian University, and Magdalena

Okońska-Bulas, MA.

[4]

On the

settlement from the Roman period and the early phase of

the migration period in Jakuszowice see Godłowski 1986;

Godłowski 1991; Godłowski 1995; Kaczanowski – Rodzińska

Nowak 2010. On monetary finds

at this site: Bursche 1997a; Bursche – Kaczanowski –

Rodzińska-Nowak 2000; Bodzek 2021; further bibliography

there.

[5]

Zagórzyce: Grygiel – Pikulski – Trojan 2009a; Grygiel –

Pikulski – Trojan 2009b; Bodzek 2009; Bodzek et al.

2016; Bejsce: Opozda 1967; Kunisz 1985, 24 f. no. 4;

Kaczanowski – Margos 2002, 9 no. 13; Kasiński – Bulas –

Okońska 2019.

[6]

Cf.

Kaczanowski – Margos 2002, 36 nos. 88–89; Komorowska

2014, 10 (Chwalibogowice); Kaczanowski – Margos 2002,

306–307 no. 728 (Stary Korczyn); ibidem 338 no. 822

(Uściszowice); ibidem 353 no. 875 (Wyszogród).

Further

bibliography there.

[7]

Roman denarii

found in the Przeworsk culture settlement in Trębaczów

will be the subject of a separate study.

[8]

Nota bene, it is

worth considering to what extent similar situations

affect the level of registration of finds. This

especially applies to discoveries made by so-called

detectorists, who when making uninteresting finds such

as such shapeless corroded copper nuggets might simply

throw them away. We thank Dr. K. Myzgin for this remark.

[9]

Zograph 1951,

204–205; Frolova 1997a, 149–153, especially p. 152 type

16.

[10]

Anokhin 1986, 116, 165 no. 618a.

[11]

It cannot be

ruled out that the bronze found in Gąski, Inowrocław

district (cf. table 1, no. 7) should be dated to

the

to the reign of Sauromates II.

A precise definition of this poorly preserved coin,

known to the authors of the present text only from

photographs, is not possible cf. Bodzek – Madyda-Legutko

2018, Cat. 1.

[12]

Ibidem, Cat. 5.

[13]

Bodzek –

Madyda-Legutko 2013; Bodzek – Madyda-Legutko 2018, Cat.

4.

[14]

Ibidem, Cat. 6.

[15]

Ibidem, Cat. 2.

[16]

Ibidem, Cat. 3

[17]

Cf.

note 11.

[18]

Cf. Bodzek – Madyda-Legutko 2018, 56–57.

[19]

Cf.

Bodzek – Jellonek – Zając 2019, 69.

[20]

Personal communication; the piece is stored in the

St. Staszic Hrubieszów Muzeum.

[21]

Beidin 2017;

Beidin 2018; Myzgin – Beidin 2012; Myzgin – Beidin 2015.

[22]

Sidarovich

2011; Sidarovich 2014; Michelbertas 2001, 58.

[23]

Bodzek – Madyda-Legutko 2018,

73–77. The Dacian direction of

the influx is less likely, although not entirely ruled

out. In today’s Romania, Bosporan coins were registered

in Horia, Tulcea County – bronze of Sauromates I (Mitrea

1964, 380 no. 52; Kunisz 1992, 158) – and in Poiana,

Galaţi County – bronze of Aspurgos (Mitrea 1978, 366 no.

63), gs. 2: 2–3 (367).

[24]

Cf.

Bodzek – Myzgin 2021.

[25]

Cf.

Dobrzańska 1999; Bodzek – Madyda-Legutko 2018, 73–77.

Among the numismatic evidence of interactions between

the populations of the aforementioned archaeological

cultures is the recording of finds of imitations of

Roman denarii, minted with the same dies, in the areas

of all three cultures; cf. Dymowski 2019a.

[26]

Cf. ibidem, especially 73–79.

[27]

Andrzejowski 2019; Andrzejowski 2021.

Further

bibliography there.

[28]

Bulas 2020.

[29]

Myzgin – Beidin 2012, 60 f.

[30]

G. Beidin (2017,

4) pointed to the possibility of assigning coins

formally classified to the first group to group 2 on the

basis of the presence of countermarks. Counter-marks

testifying to long circulation would make it possible to

distinguish between coins used before (in this case,

coins without countermarks) and during the Gothic Wars

(countermarked). However, this theory is difficult to

apply in relation to Polish finds, among which no

countermarked specimens have been registered so far. As

shown below, despite the lack of countermarks, most of

the Bosporan coins probably came to the present-day

Polish lands only at the end of the 2nd–1st half of the

3rd century AD.

[31]

Cf. Bodzek – Madyda-Legutko 2018, 67.

[32]

The problem in

this case is the very unclear relationship between these

finds. In principle, it is not known whether the coins

in question were found together, whether the finds were

made on the same day, or whether they were simply

acquired on the same day. Cf. Bodzek – Madyda-Legutko

1999; Bodzek – Madyda-Legutko 2018, 71.

[33]

A. Bursche (cf.

e.g. Bursche 1994, 472–475; Bursche

2004, 196–198;

Bursche 2006, 222) and M. Erdrich (2001,

127 f.)

date the beginning of the aforementioned wave to the

time of the Marcomannic Wars (167–180 CE). According to

R. Wolters (1999, 385–386), the influx of denarii may

have started under Antoninus Pius (138–161) or Marcus

Aurelius (161–180), and T. Lucchelli (1998, 160 f.)

indicates the period from Trajan (98–117) to Antoninus

Pius as the beginning of the great wave of Roman silver.

A. Dymowski allows for three possibilities of the

arrival of the first imperial denarii: 1) in the final

period of Trajan’s reign (in connection with the Dacian

Wars [101–106]); 2) in the final years of Hadrian’s

reign (117–138) or during the reign of Antoninus Pius;

or 3) the beginning of a first large wave in the middle

of the reign of Antoninus Pius or under Marcus Aurelius,

and another great wave in the first years of the reign

of Septimius Severus (Dymowski 2013, 111–114). The end

of the influx of the great wave of denarii would have

taken place according to various concepts at the time of

Commodus (177–192) or at the beginning of the reign of

Septimius Severus (193–211) (e.g. Bursche 1994; Bursche

2006, 222; Lucchelli 1998, 160–162; Wolters 1999,

385–386; Erdrich 2001, 127 f.; Dymowski 2013, 113).

[34]

Cf. Dymowski 2019a.

[35]

A. Bursche and

A. Dymowski date the influx of third-century denarii to

the years 30–40 of the 3rd century AD. Cf. Bursche 2004,

201; Dymowski 2013, 113–114); on the problem of the

influx of Roman coins minted in the 3rd century AD and

later see Bursche 1996; Dymowski 2012; Dymowski 2013;

the issue of subaerati, copies and imitations of Roman

coins in Poland are discussed in Bursche 1997b; Bursche

– Kaczanowski – Rodzińska-Nowak 2000; Dymowski 2017;

Dymowski 2019a; Dymowski 2019b; Dymowski 2020; Dymowski

2021; Romanowski – Dulęba 2018; Więcek 2019. Of course,

we cannot exclude the production of some subaerati,

imitations or copies in the area of Wielbark or the

Przeworsk culture (cf. Dymowski 2020). Dymowski 2018

presented general comments on the influx of Roman coins

to the area of Lesser Poland.

[36]

On finds of Greek

coins minted before the 1st century BC see Mielczarek

1989; Mielczarek 1996; Mielczarek 2008; about Celtic and

other barbarian coins, e.g. Rudnicki 2012a; Rudnicki

2012b; Rudnicki 2013; Rudnicki –Miłek 2009; Rudnicki

–Miłek 2011; Florkiewicz 2009; Dulęba – Wysocki 2017; on

coins of the Roman Republic Dymowski 2016; Dymowski –

Rudnicki 2019.

[37]

Cf.

Bodzek – Jellonek –

Zając 2019.

[38]

Cf.

Bodzek – Jellonek – Zając 2019, 68.

[39]

Cf.

Myzgin 2011; Myzgin 2012; Myzgin 2015; Myzgin 2017;

Myzgin 2018.

[40]

On the

possibility of influx to the Barbaricum of the 3rd

century AD denarii and antoniniani thanks to the

contacts between the Roman Empire and the Goths (i. e.

de facto the Cherniakhiv culture), see Dymowski 2013,

114; Dymowski 2017; Dymowski 2018, 46; Dymowski 2019a.

[41]

Myzgin – Beidin 2012.

[42]

Cf.

Bodzek – Jellonek – Zając 2019, 70; Bodzek 2021.