[Die Combinations of] Unrelated Obverses and Reverses of Ancient Coins in Jacopo Strada’s Numismatic Works

Zusammenfassung:

In dem Beitrag werden einige dieser

Stempelkombinationen vorgestellt und es wird der Frage

nachgegangen, was Strada zu diesen Zusammenstellungen veranlasst

haben könnte. Hat er diese Münzen wirklich gesehen, d. h.

existierten sie zu seiner Zeit und sind nicht auf uns gekommen

oder hat er sie komplett ›erfunden‹?

Dazu sollen auch die Werke seiner Zeitgenossen herangezogen

werden (Pirro Ligorio, Sebastiano Erizzo, Antonio Agustín), um

zu überprüfen, ob sich diese möglicherweise erfundenen

Stempelkombinationen auch in deren Werken wiederfinden. Dadurch

ergeben sich neue Einblicke in die Arbeits- und Vorgehensweise

renaissancezeitlicher Antiquare.

Schlagwörter: Jacopo Strada

http://d-nb.info/gnd/118834320, Geschichte der Numismatik,

Münzaverse und -reverse, Stempelkombinationen, Antiquare der

Renaissance,

Pirro Ligorio

http://d-nb.info/gnd/118779966, Enea Vico

http://d-nb.info/gnd/119099950, Antonio Agustín, Hubertus

Goltzius

http://d-nb.info/gnd/138826153, Sebastiano Erizzo

http://d-nb.info/gnd/139904328

Abstract:

In his surviving numismatic manuscripts (i.e.

Magnum ac Novum Opus, Diaskeué, Series

Imperatorum Romanorum) Jacopo Strada describes coin obverses

and reverses as belonging together, when in reality they had

originally been part of coins displaying other obverses and

reverses. In some volumes of the MaNO and Diaskeué,

the occurence of such coins is very high (e.g. coins of

Augustus, Antoninus Pius, Marcus Aurelius). By naming their

sixteenth-century owners in the Diaskeué, Strada gave

them a supposedly secure authenticity.

My contribution presents

some of these ›combinations‹ and examines what may have prompted

Strada to create them. Did he really see these coins, i.e. did

they exist in his time but have not been preserved, or did he

completely ›invent‹ them? This investigation will also involve

the works of his contemporaries (Pirro Ligorio, Sebastiano

Erizzo, Antonio Agustín) to check whether such potentially

invented ›combinations‹ can also be found in the works of other

antiquarians. This investigation will also provide new insights

into the work and approach of renaissance antiquarians.

Key words:

Jacopo Strada, history of numismatics, coin obverses and

reverses, die combinations, renaissance antiquarians, Pirro

Ligorio, Enea Vico, Antonio Agustín, Hubertus Goltzius,

Sebastiano Erizzo

Jacopo Strada (b.

1505‒1515, d. 1588), an antiquarian from Mantua, was the author

of a considerable number of manuscripts and books dealing with

Greek coins, coins of the Roman Republic and the Roman emperors

to the mid-sixteenth century[1].

According to his own statement, the Diaskeué should

provide the complementary coin descriptions to his corpus of

drawings of coins of the Roman emperors[2].

I.

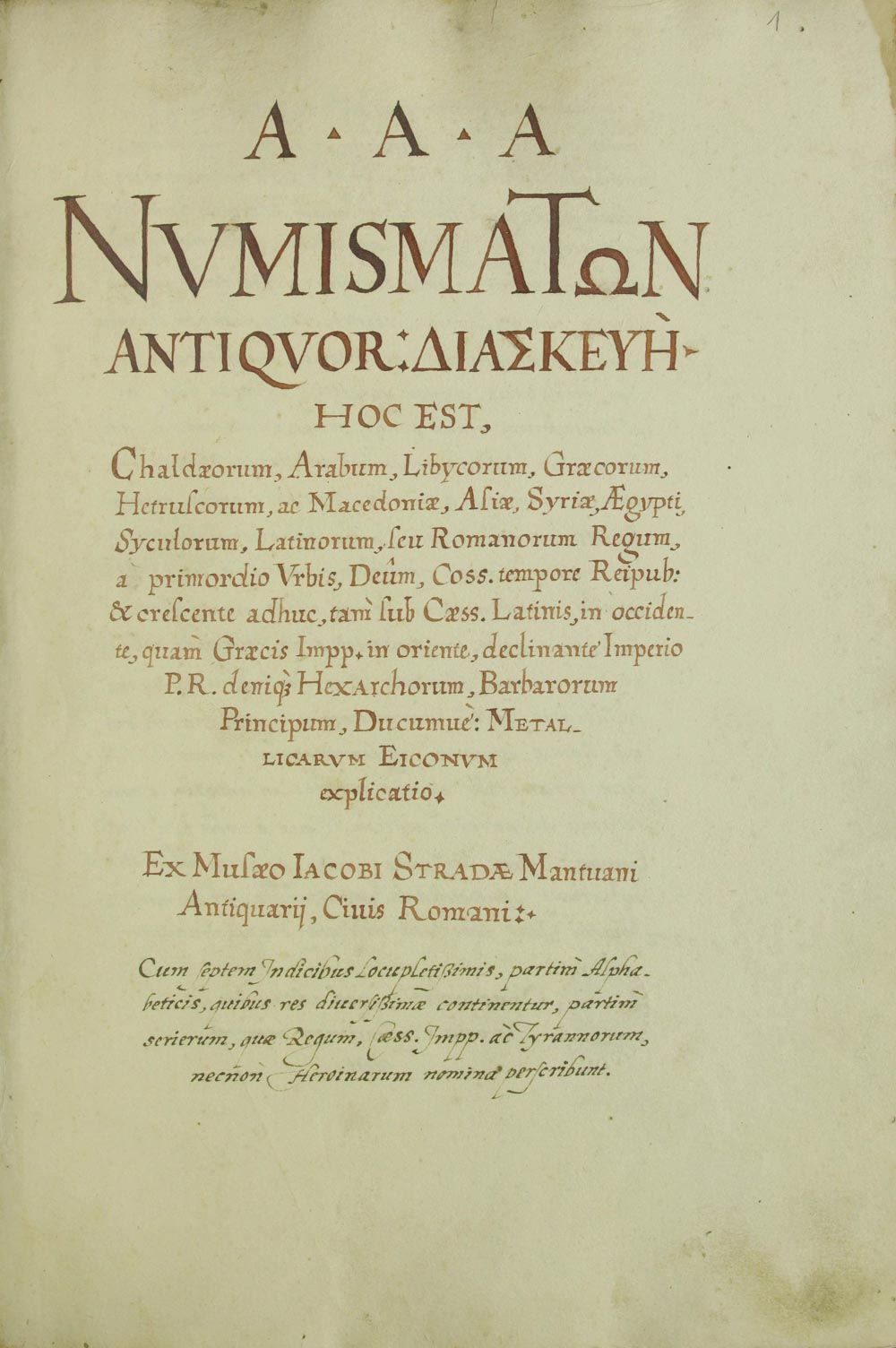

In the Diaskeué

(fig. 1a), the eleven-volume work with

descriptions of coins from antiquity to his own time, Strada

presented coin obverses and reverses as if they belong together,

when in reality they had actually been combined with other

obverses and reverses[3].

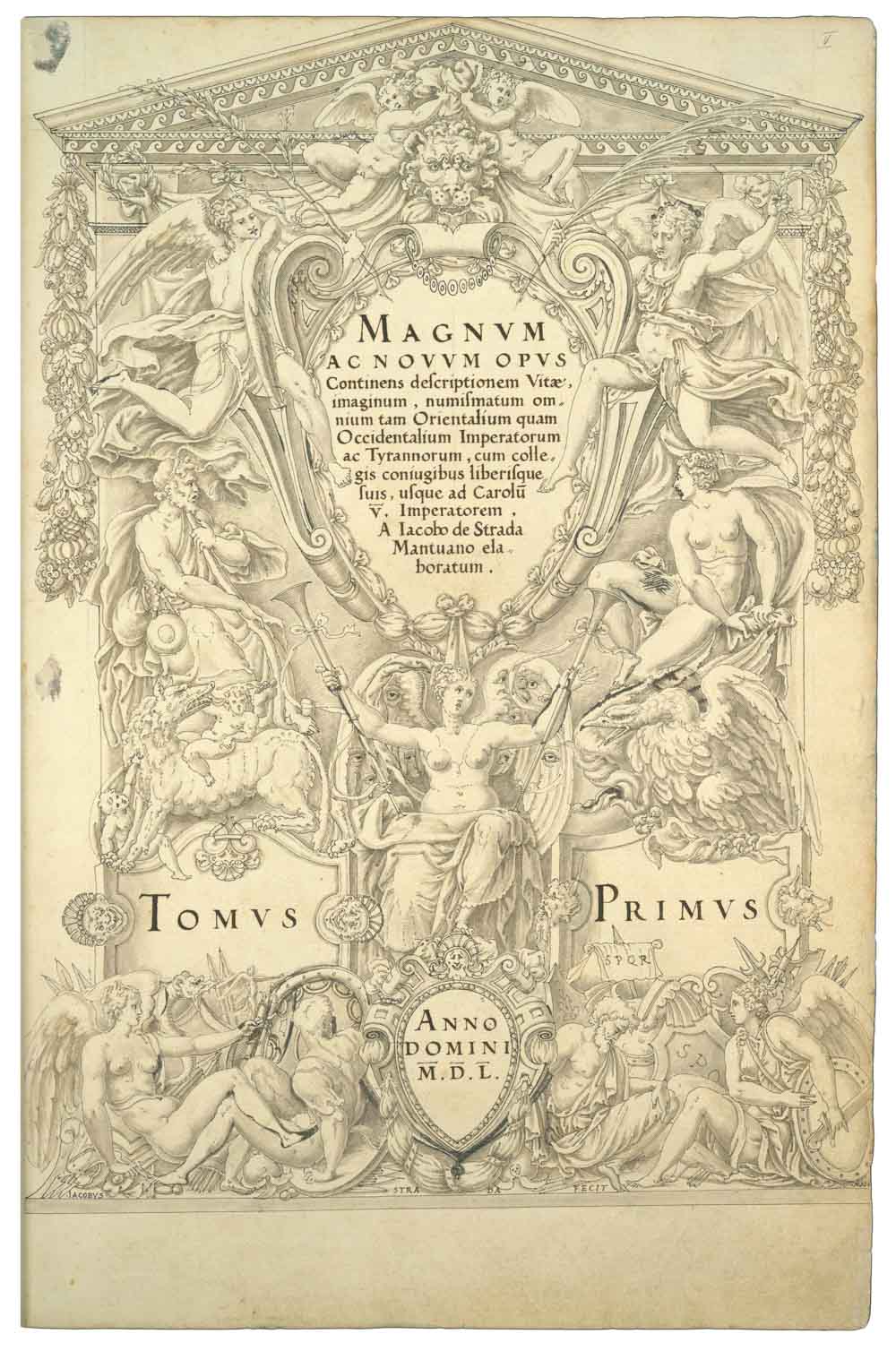

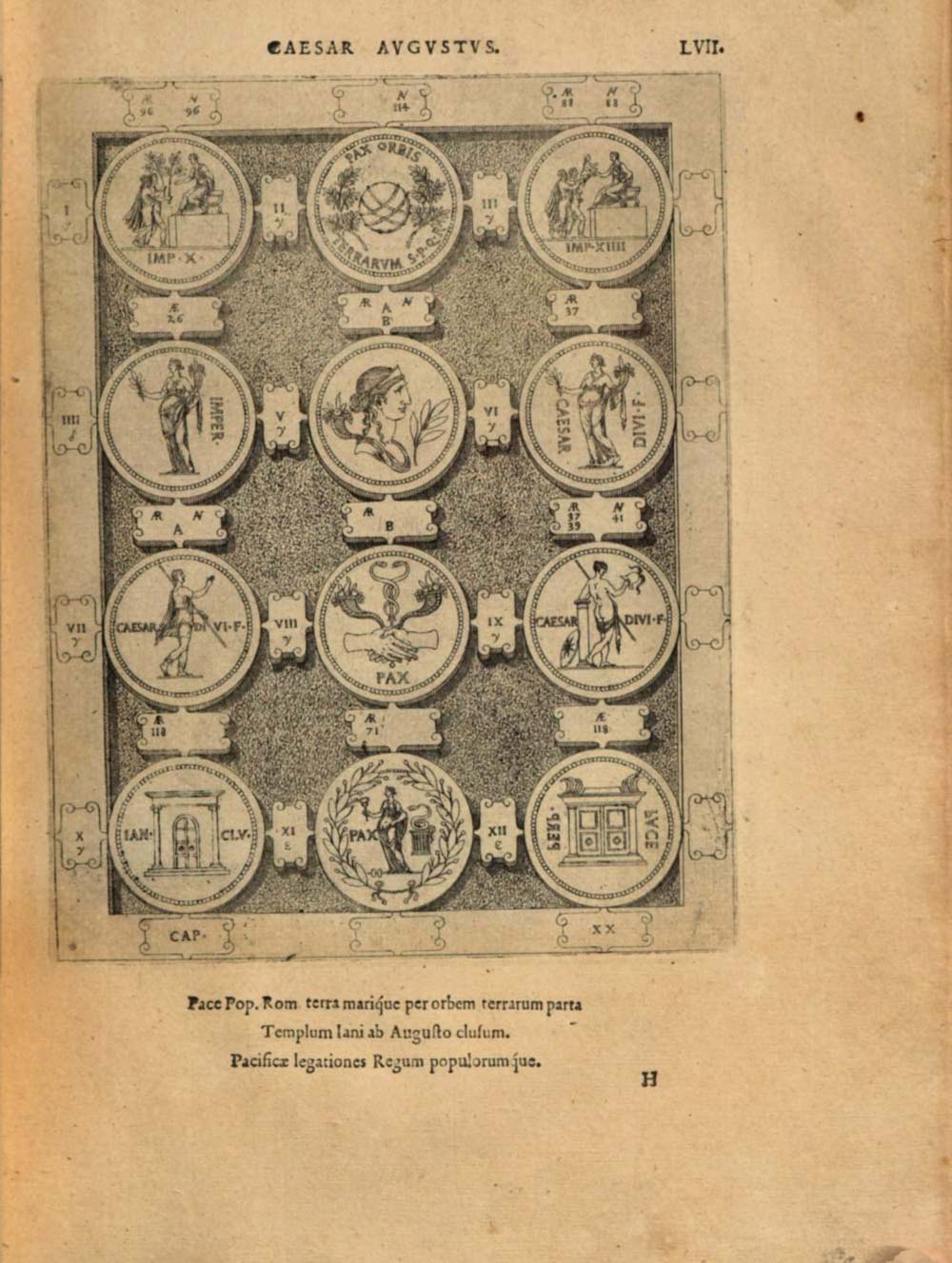

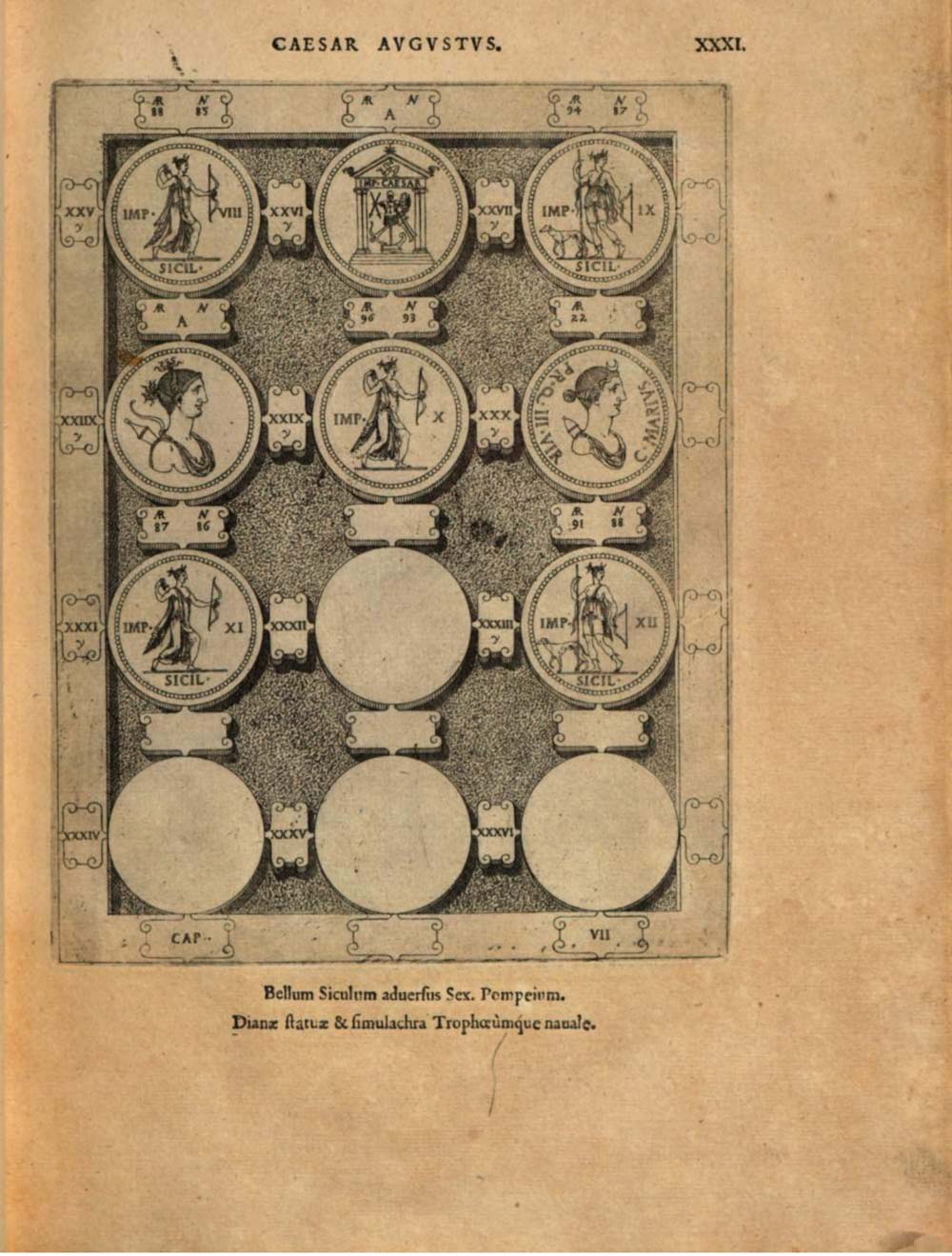

Illustrations of these fictitious combinations can also be found

in the MaNO (fig. 1b), a corpus of

coin drawings from antiquity to the days of Charles V, which

includes over 8,500 examples[4].

I limited the selection

to the coins of Augustus, since in this case the comparative

material was the largest: Coins illustrated in the works of Enea

Vico, Antonio Agustín, Sebastiano Erizzo, Hubertus Goltzius and

Pirro Ligorio may be compared. Moreover, in his Discorsi

of 1592, Antonio Agustin listed the above-mentioned

antiquarians, as well as Strada. These scholars and collectors

seem to have formed some kind of numismatic circle and exchanged

information and coin drawings among them[5].

The work of Sebastiano Erizzo – who

played an important role during this sixteenth-century ›boom‹ of

numismatic antiquarian literature – has also been included in

this study, even though Agustín never mentioned him[6].

Strada also names the above-mentioned

antiquarians and coin collectors in the Diaskeué.

II.

The descriptions of

unrelated coin obverses and reverses from the reign of Augustus

can be found in the second volume of the Diaskeue[7].

The illustrations in the MaNO are however presented in

several volumes: e.g. the coins of Caesar (vol. 1), of Octavian

and Lepidus (vol. 2) and of Augustus (vols. 4–6). As a rule, in

the MaNO obverses and reverses are always shown together.

Unfortunately, this original order seems to have been somewhat

disturbed by the rebinding initiated by Duke Albrecht in 1571.

In total, the material under consideration concerns 16 out of

208 descriptions.

III.

They can be classified

as follows:

1. Coin descriptions

with incorrect die combinations included in the Diaskeué

which are presented in exactly the same way in the MaNO.

2. Coin descriptions

with incorrect die combinations included in the Diaskeué,

the illustrations of which (usually of the reverse) are also

included in the MaNO, even though they are located in

different places as well as in different volumes.

3. Coin descriptions

with non-existent die combinations included in the Diaskeué,

the obverses and reverses of which are however shown in the

correct combination in the MaNO.

IV.

In what follows, I shall

briefly present these coins and document whether they can be

found in the above-mentioned antiquarian works and in which way

they are depicted or described therein.

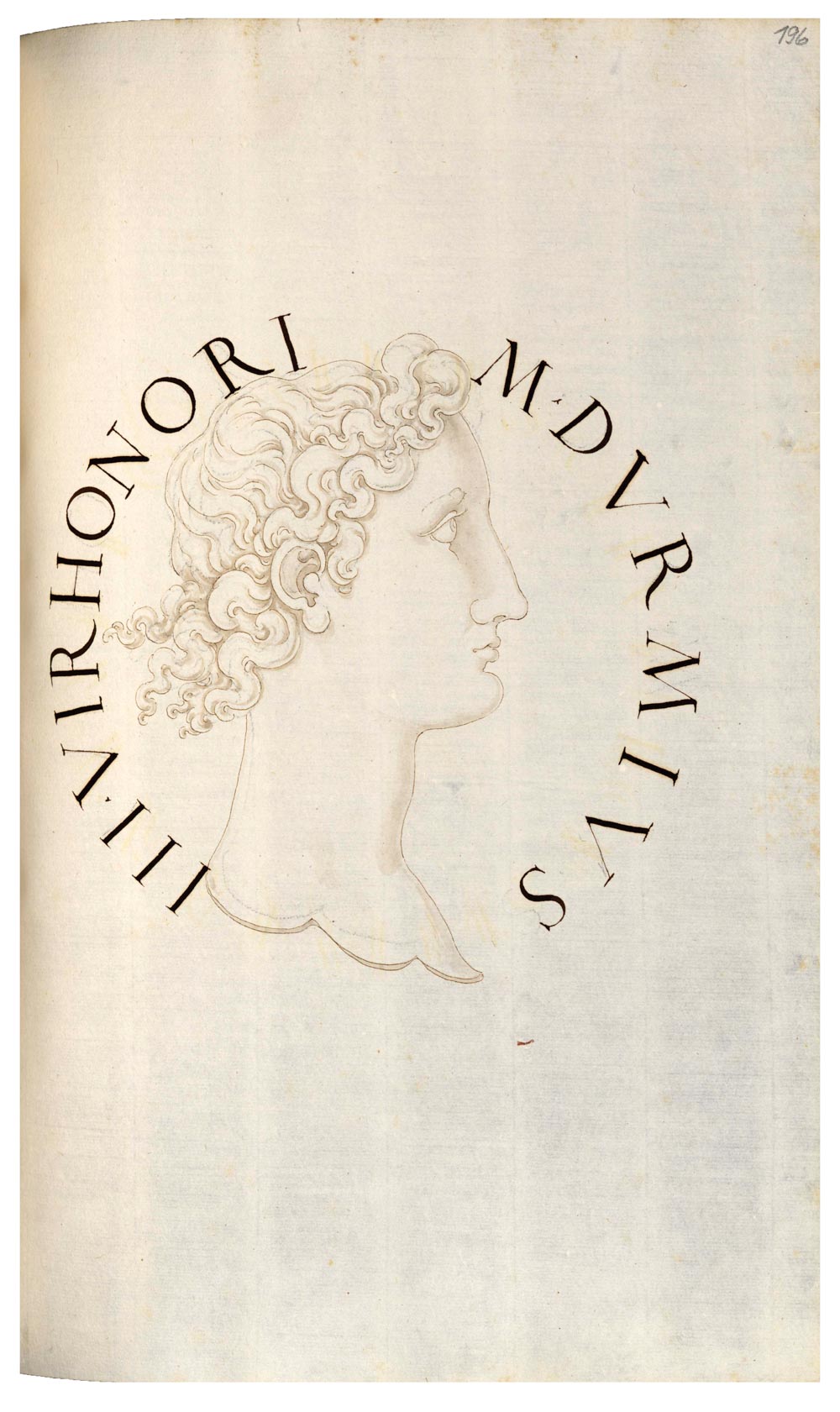

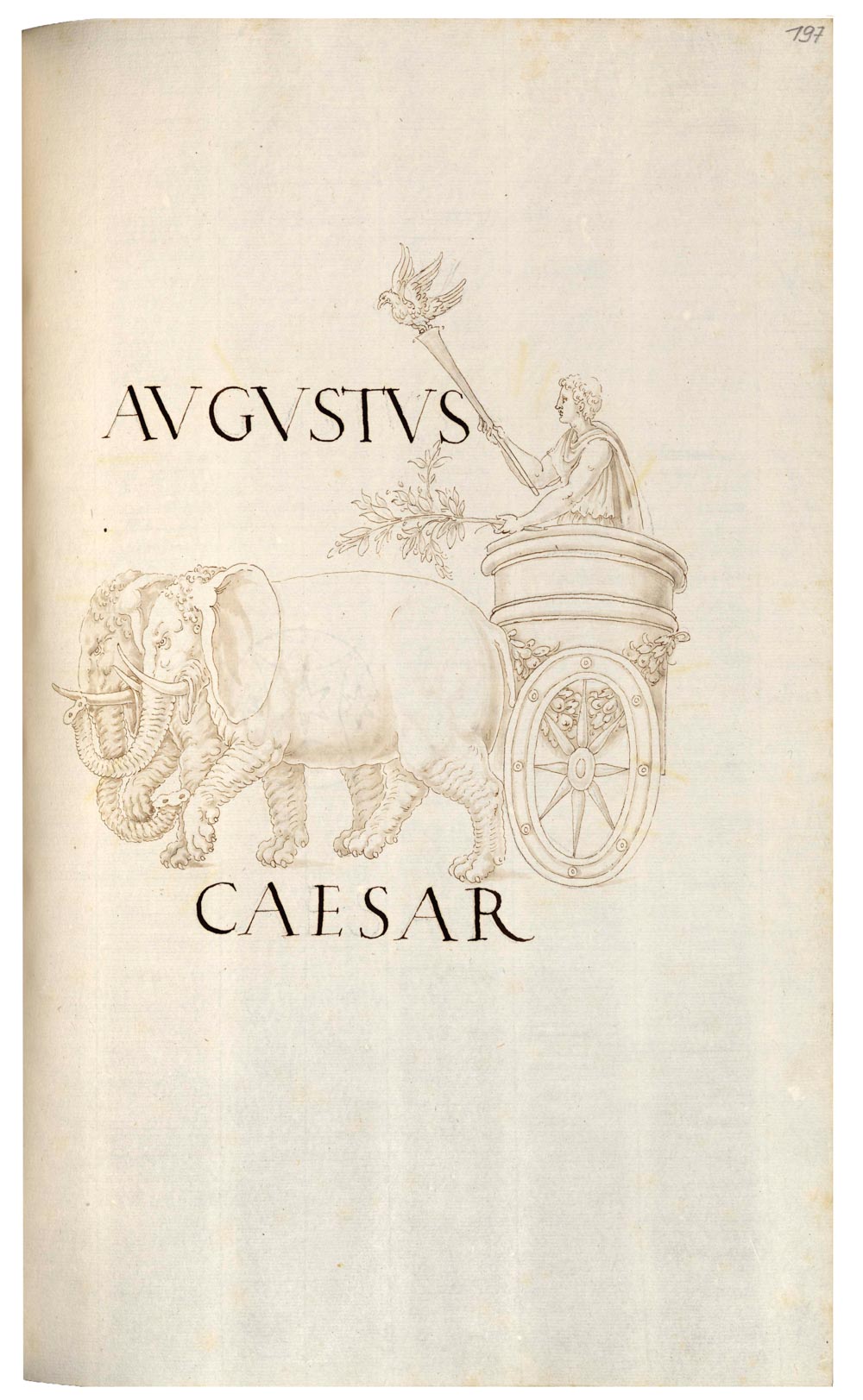

1.1

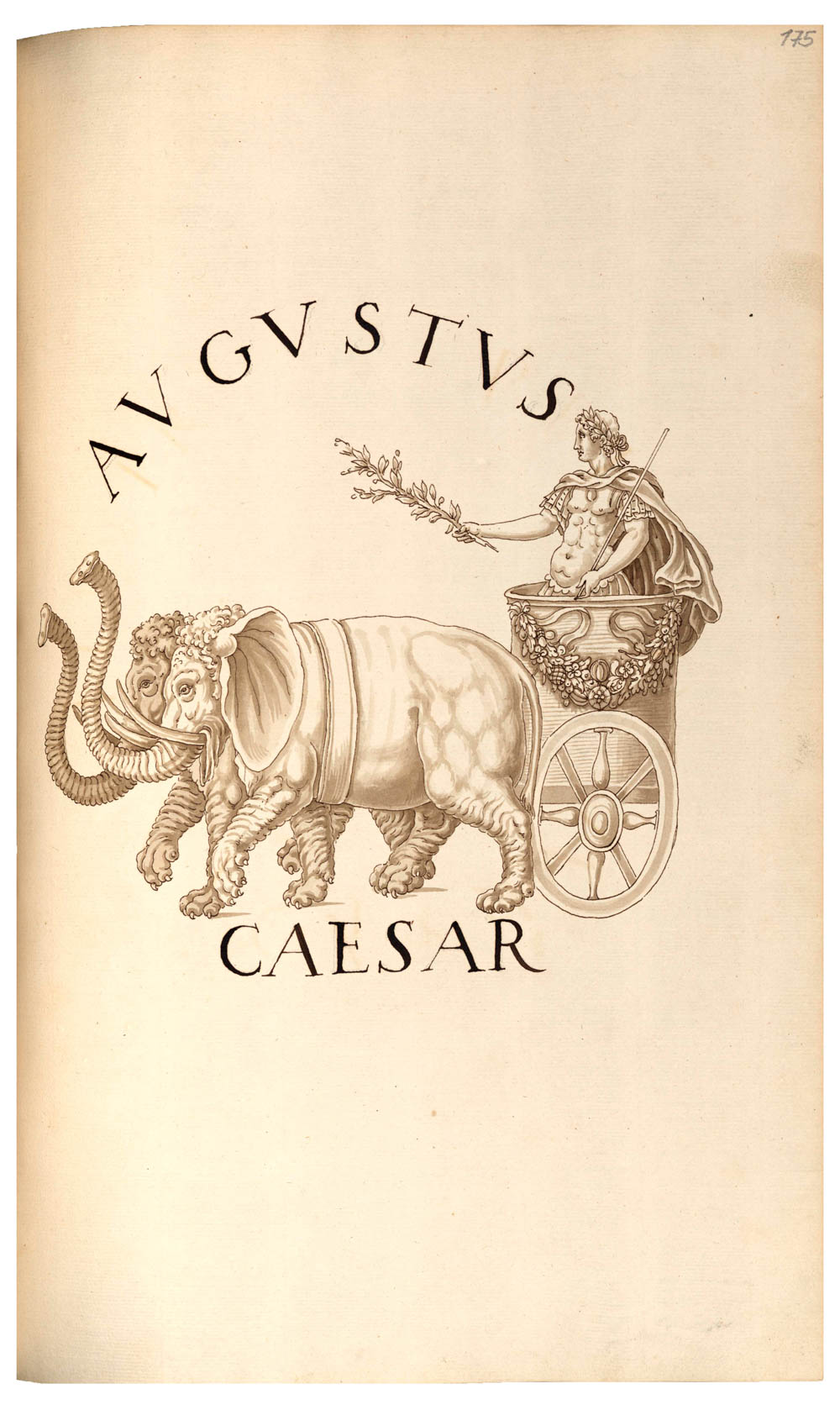

Coins of the first group include fols. 196r (fig. 2a:

male head, legend: M DVRMIVS IIIVIR HONORI)[8]

and 197r (fig. 2b: Augustus in elephant biga, legend:

AVGVSTVS CAESAR)[9]

in the fourth volume of the MaNO. The description is to

be found in the second volume of the Diaskeué fol. 156r

no. 57. According to Strada the owner was Grand Duke of Tuscany,

Francesco I de Medici. This coin is only listed by Strada.

Neither Vico, Goltzius, Erizzo, Agostin nor Ligorio illustrate

it.

1.2

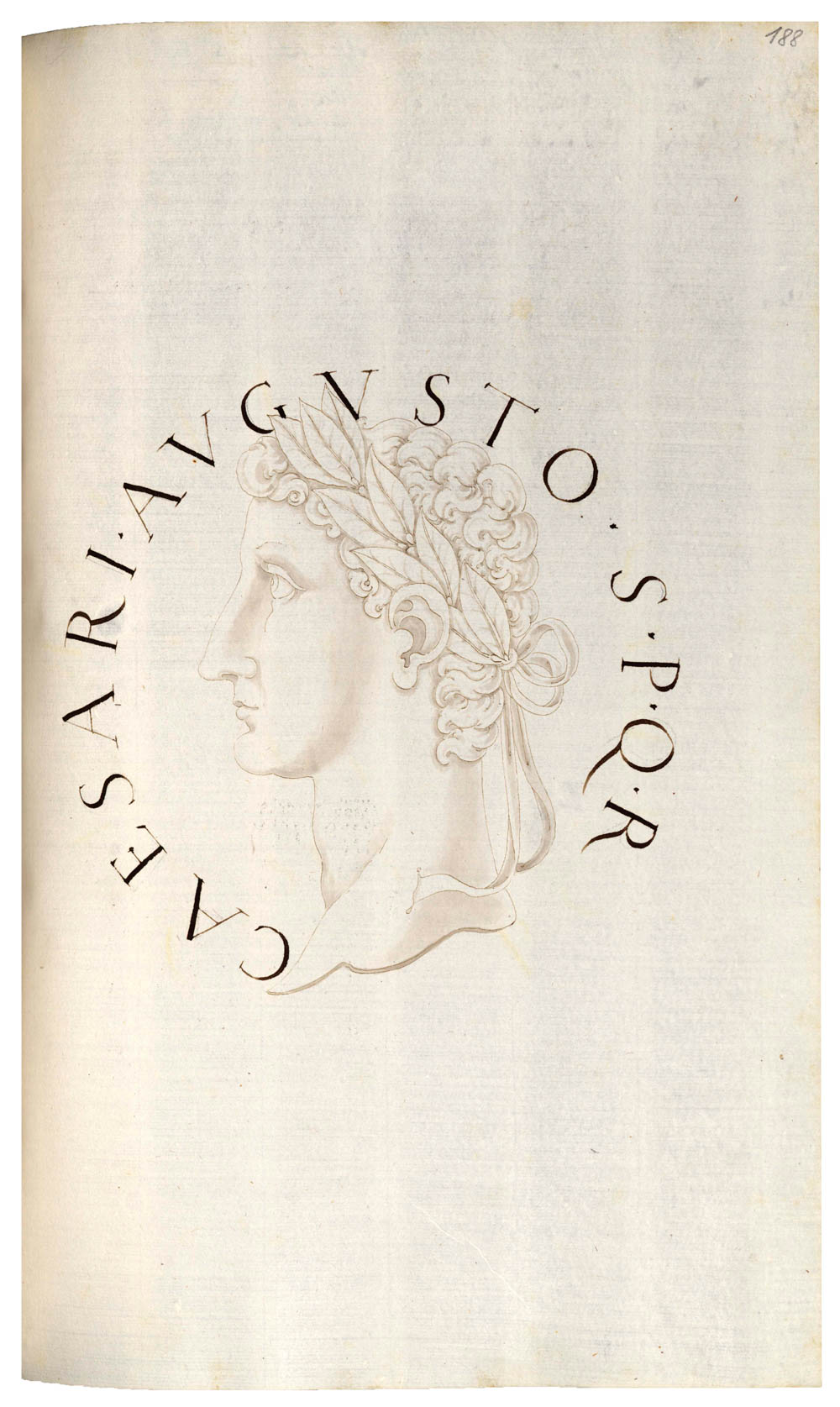

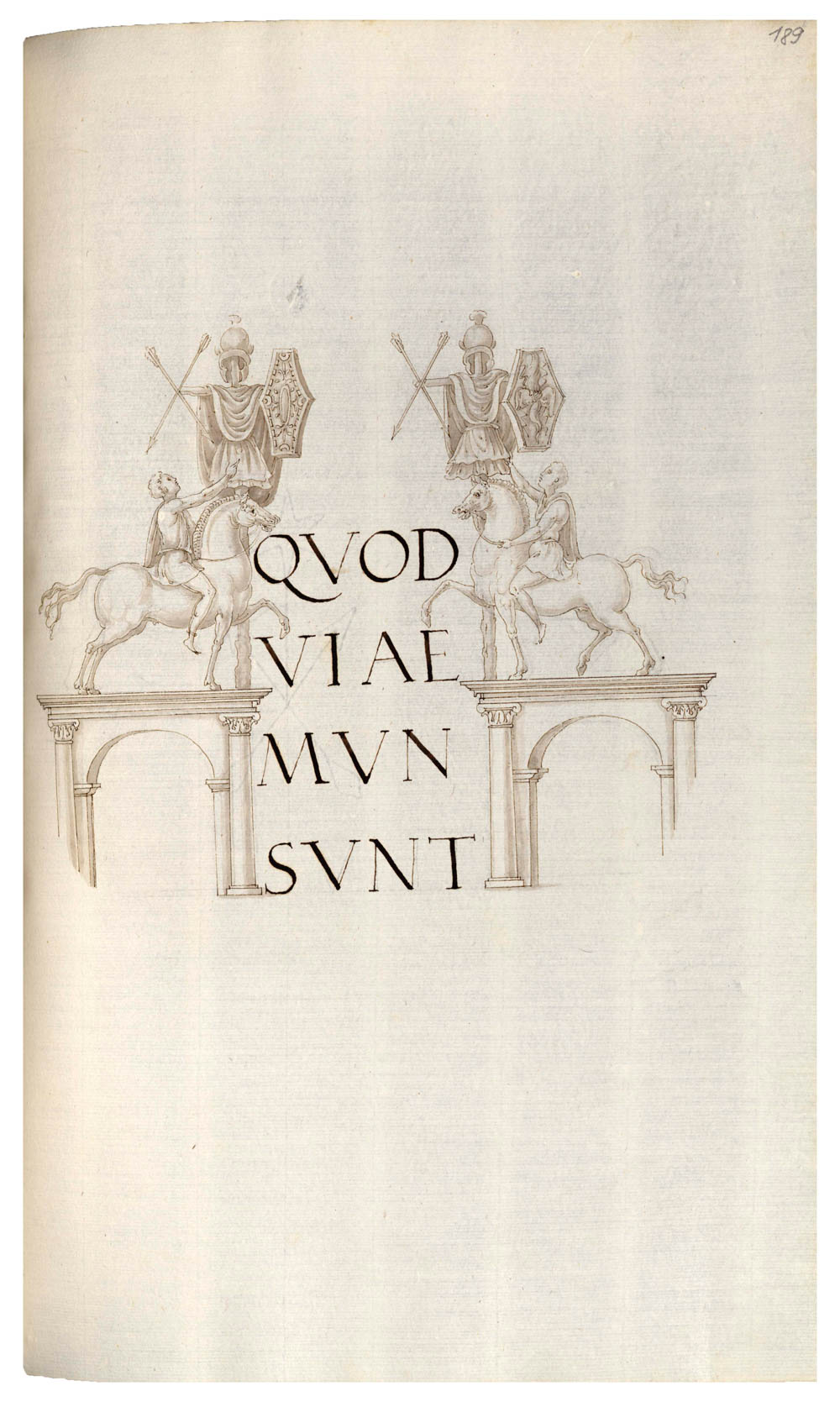

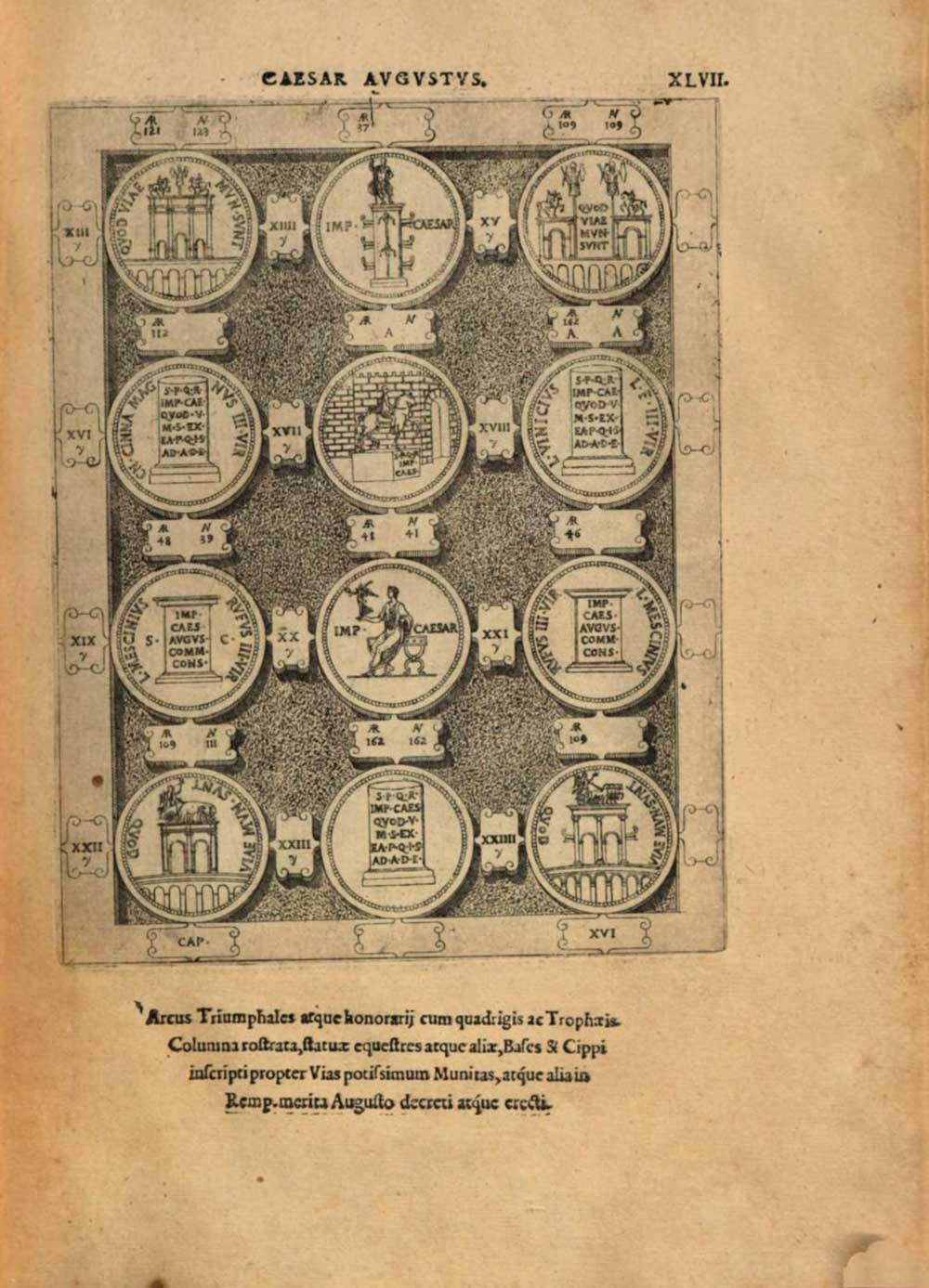

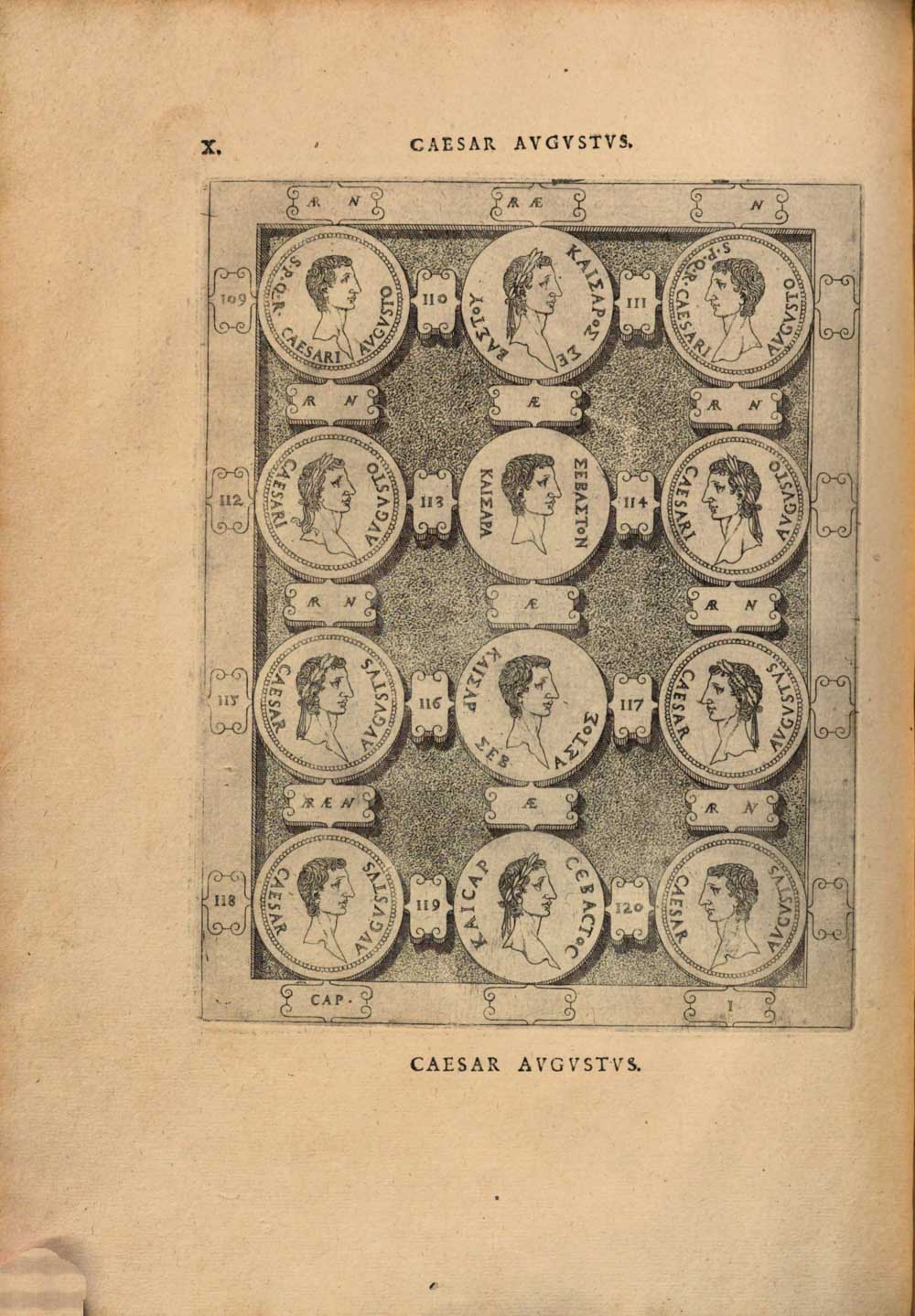

The second coin is to be found on fols. 188 (fig. 3a:

Augustus laureate, legend: S P Q R CAESARI AVGVSTO) and 189 (fig.

3b: two arches with two equestrians, legend: QVOD VIAE MVN

SVNT)[10]

in the fourth volume of the MaNO. It

is described in the second volume of the Diaskeué (fol.

159v no. 74). Strada states that the Doge of Venice (1554–1556),

Francesco Venerio, was the owner. Of the contemporary

antiquarians, Hubertus Goltzius (figs 4a and b: Caesar

Augustus pl. XLVII, b: pl. X)[11]

and Sebastiano Erizzo depict this coin while Strada describes

and depicts it – Erizzo only the reverse, but from the matching

description it is evident that he described the same coin as

Strada[12].

Vico only included a description of this coin but provided the

matching obverse in his Discorsi[13].

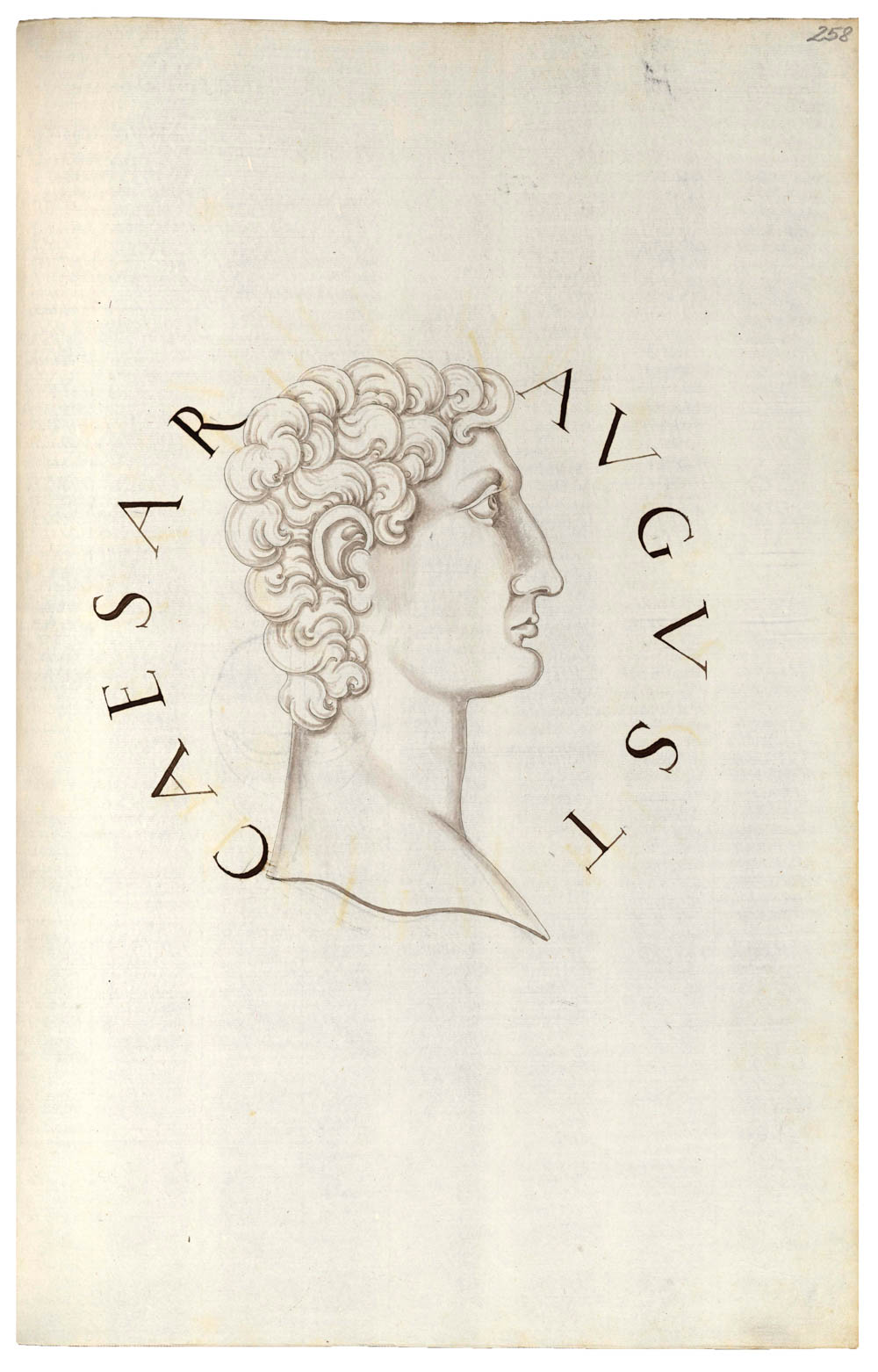

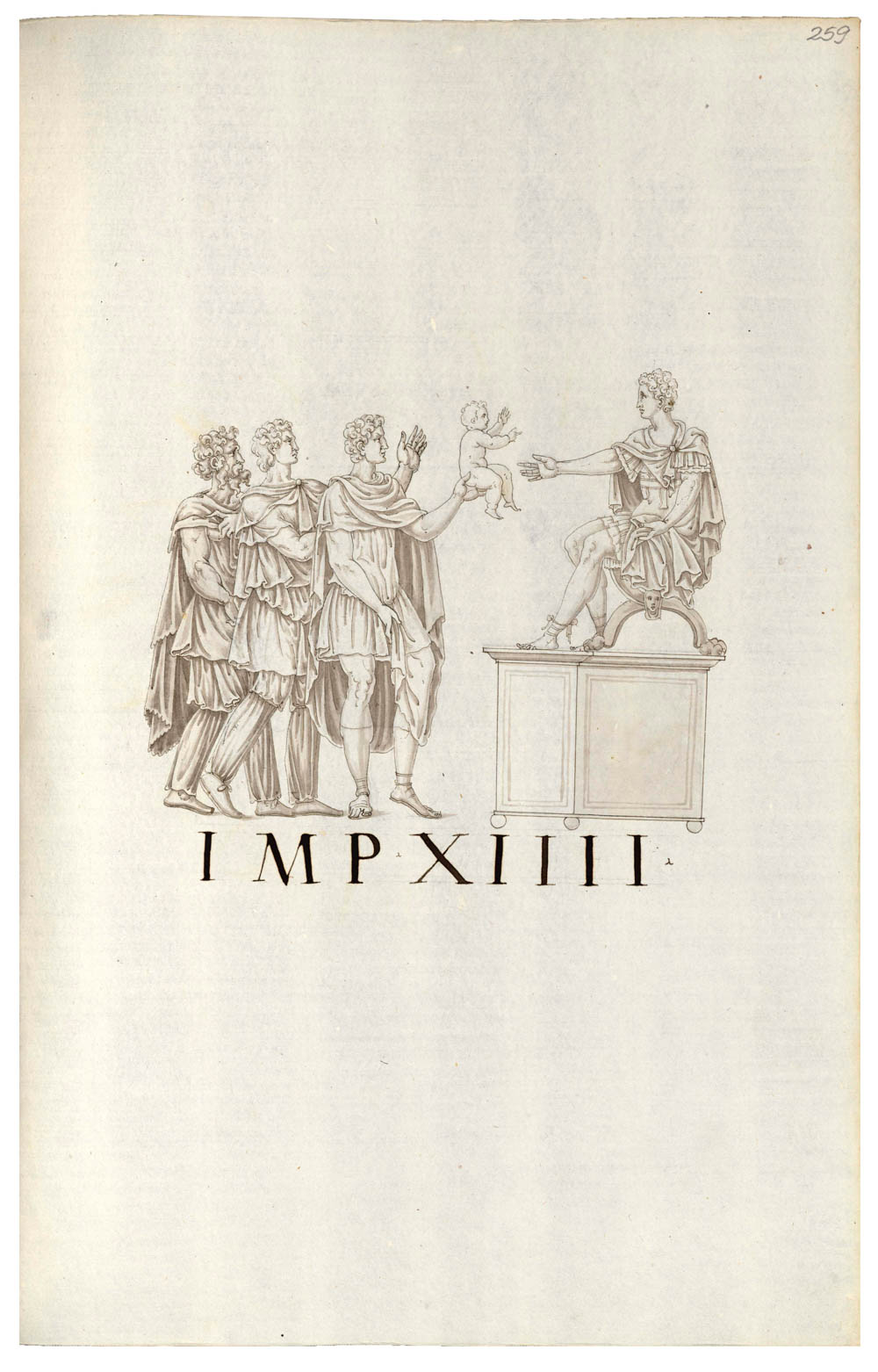

1.3

Of the third coin, both obverse and reverse are included

in the fourth volume of MaNO on fols. 258r (fig. 5a:

Augustus looking right, legend: CAESAR AVGVST) and 259r (fig.

5b: Imperator on platform, in front three officers

presenting a child, legend: IMP XIIII)[14].

The description can be found in volume 2 of the Diaskeué

on fol. 164r no. 96. Strada mentions as owner his mentor in

antiquarian-numismatic scholarship, the Lyon antiquarian

Guillaume du Choul (1496–1560), advisor to the French king and

bailiff of the Dauphiné[15].

With the exception of Goltzius, no other antiquarian illustrates

this coin. Goltzius depicts the reverse as it is in Strada, i.e.

with three officers standing before the emperor rather than one

officer as can be seen on the coin, on which the drawing is

based (figs 6a and b)[16].

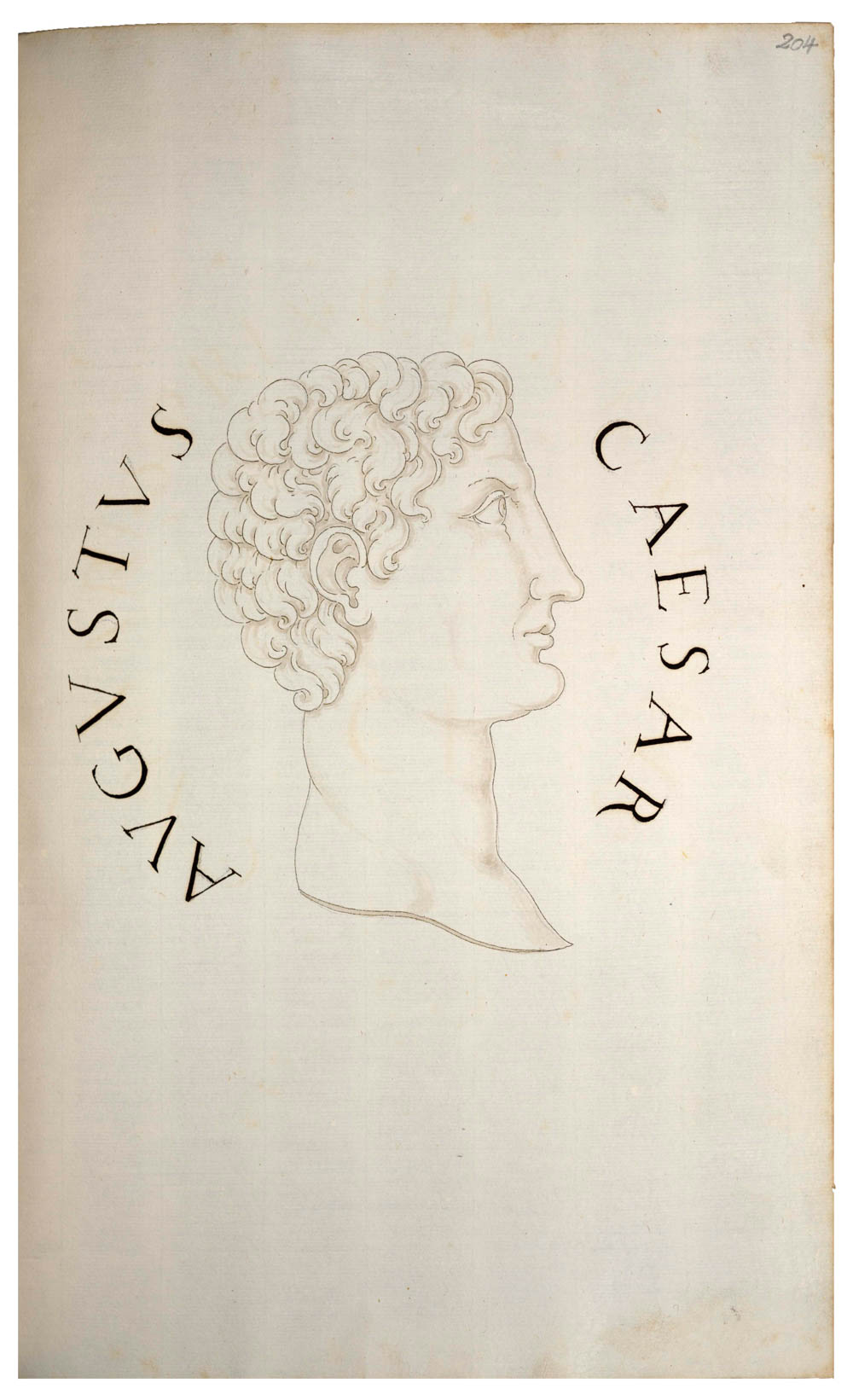

1.4

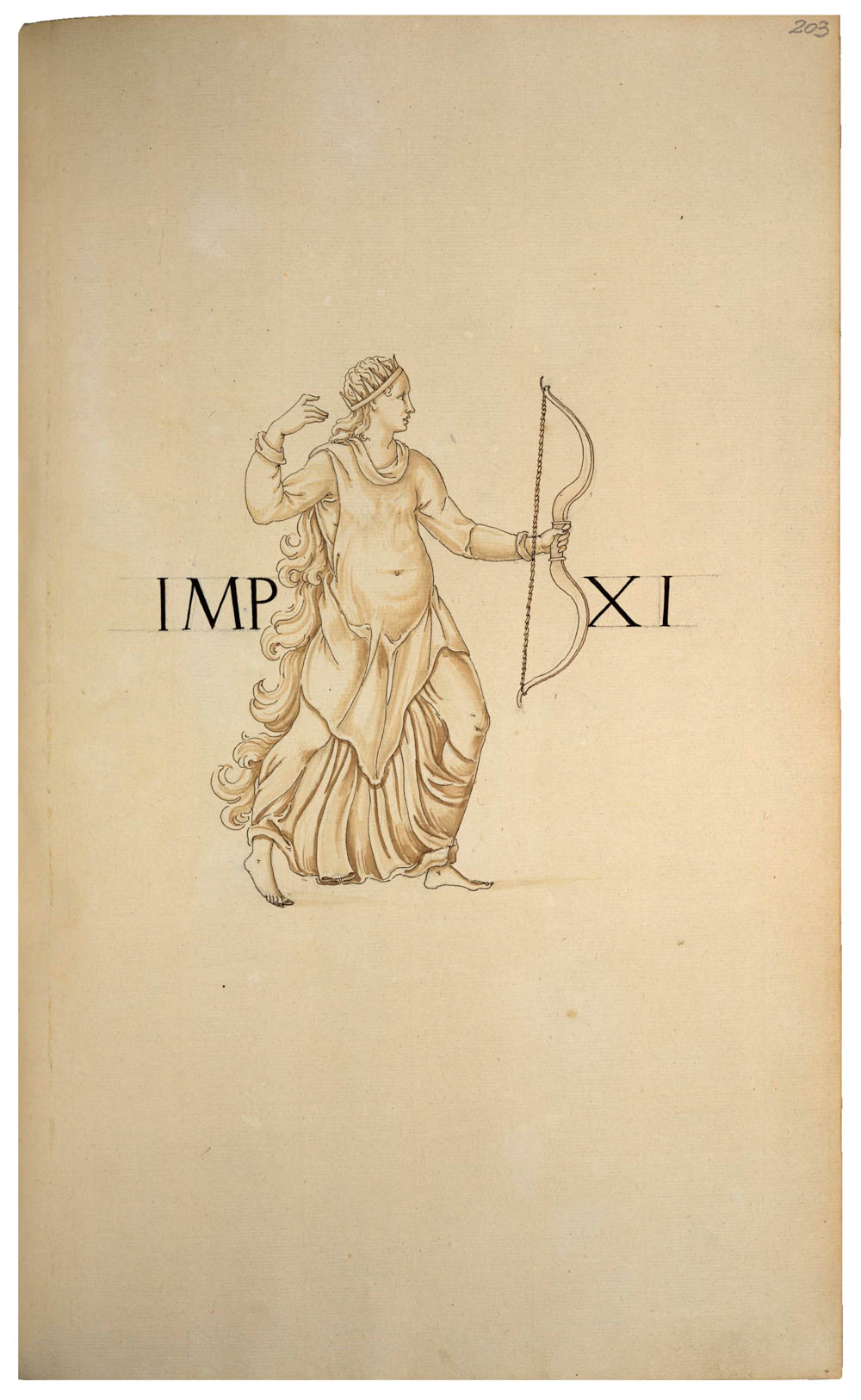

The fourth and last coin is illustrated on fols. 204r (fig.

7a: Augustus looking right, legend: CAESAR AVGVSTVS) and

203r (fig. 7b: Diana Venetrix, legend: IMP XI)[17]

in the fifth volume of the MaNO, with obverse and reverse

exchanged. The description can be found in the second volume of

the Diaskeué, fol. 169v no. 122, where the Bishop of

Tarragona and member of the Rota, Antonio Agustín, is named as

owner. Except for Vico (reverse only), no other antiquarian

includes it in his work[18].

The second group includes six coin descriptions:

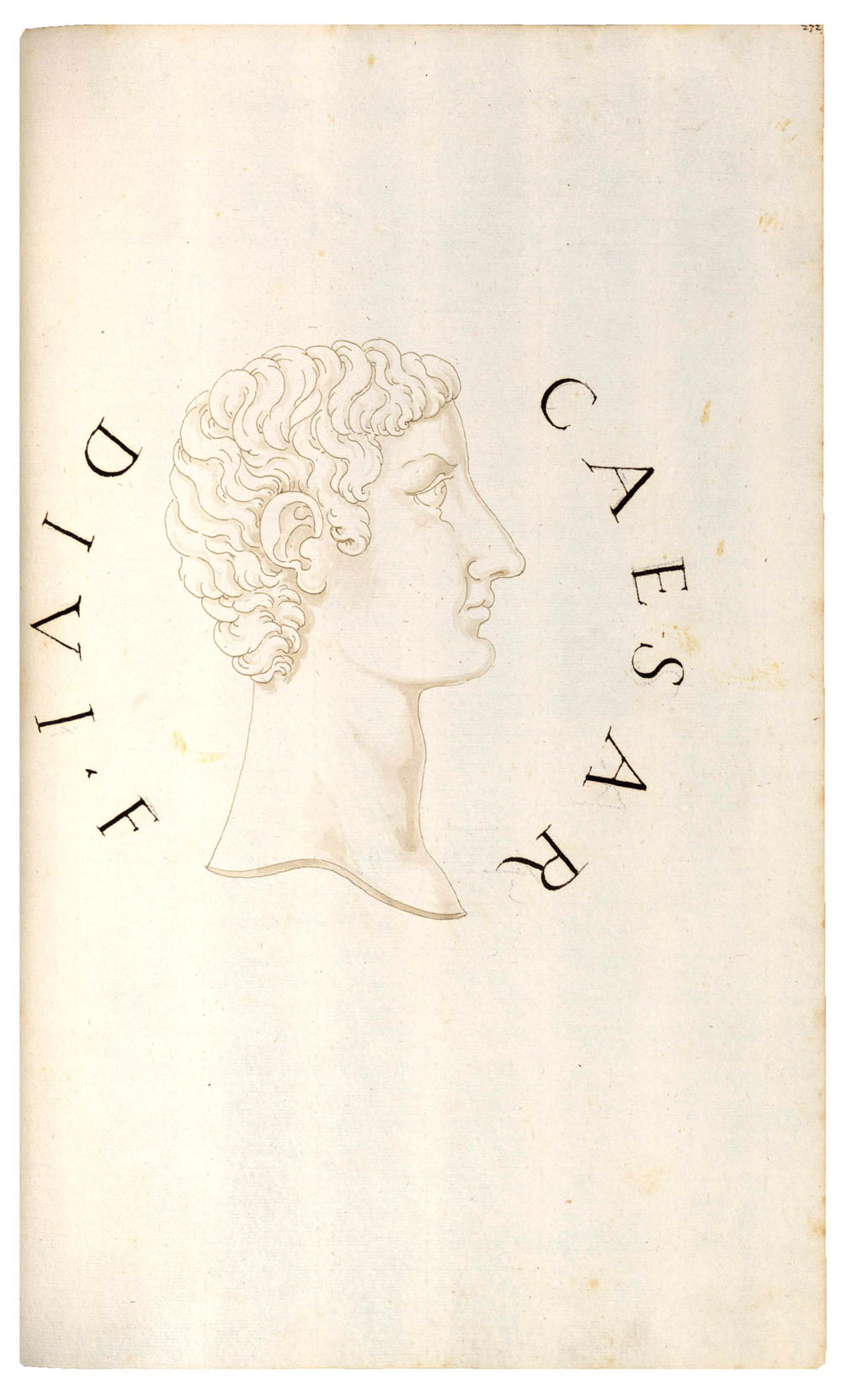

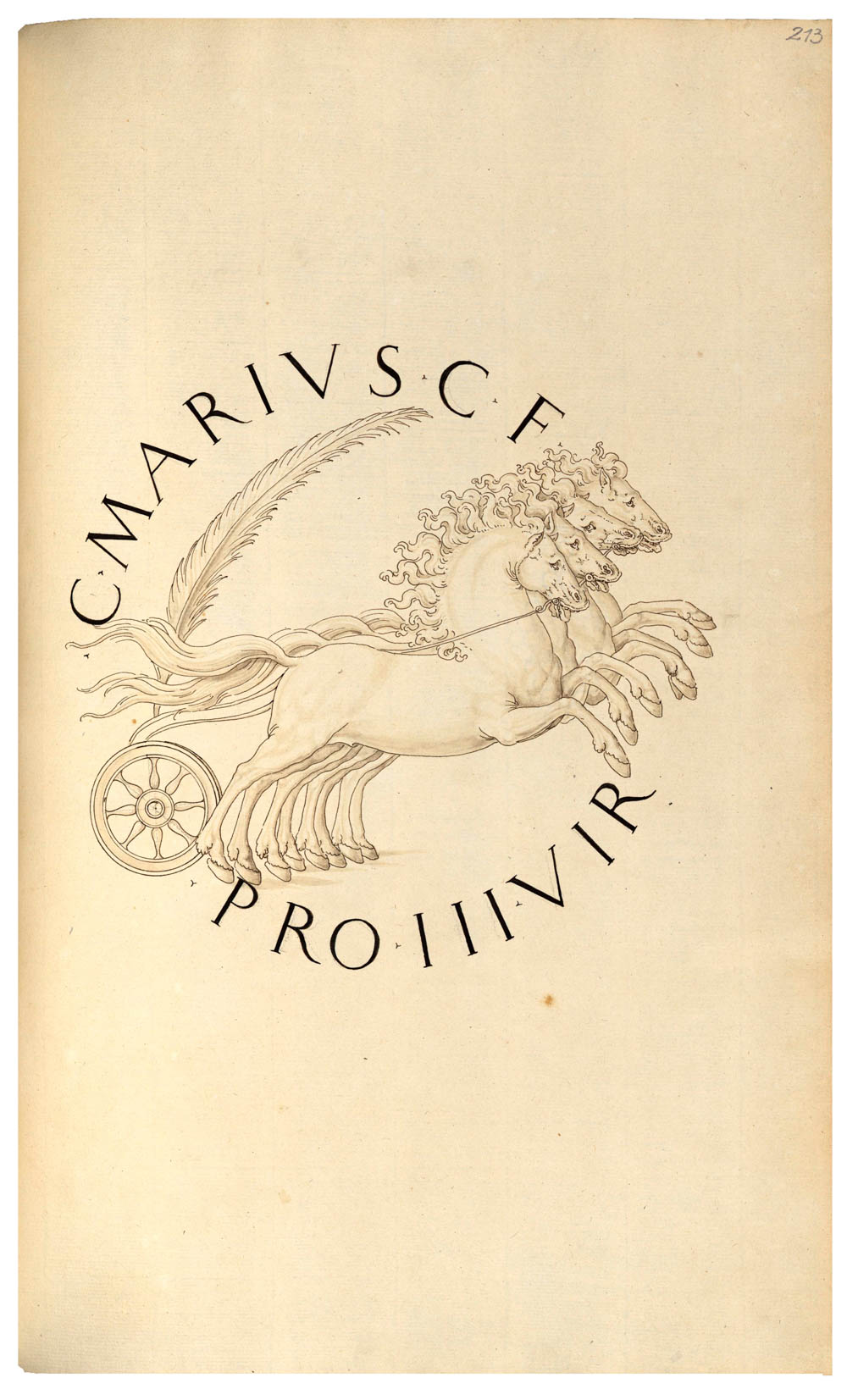

2.1 The first can be found on folio 272r (fig. 8a: Augustus looking right, legend: CAESAR DIVI F)[19] in the first volume of the MaNO and on folio 213r (fig. 8b: quadriga with palm branch, legend: C MARIVS C F PRO IIIVIR)[20] in the fourth volume. The description is included in the second volume of the Diaskeué on fol. 148r no. 15. Strada names Antonio Agustín as the owner. Enea Vico[21] and Hubertus Goltzius[22] obviously used the same source as Strada, which is confirmed by a similar error in the coin legend, i.e. C MARIVS C F PRQ III VIR instead of C MARIVS C F TRO IIIVIR on the original coin, Goltzius with the matching obverse[23]. Agustín and Erizzo do not present this coin; Ligorio however illustrates the coin with the correct obverse and reverse[24].

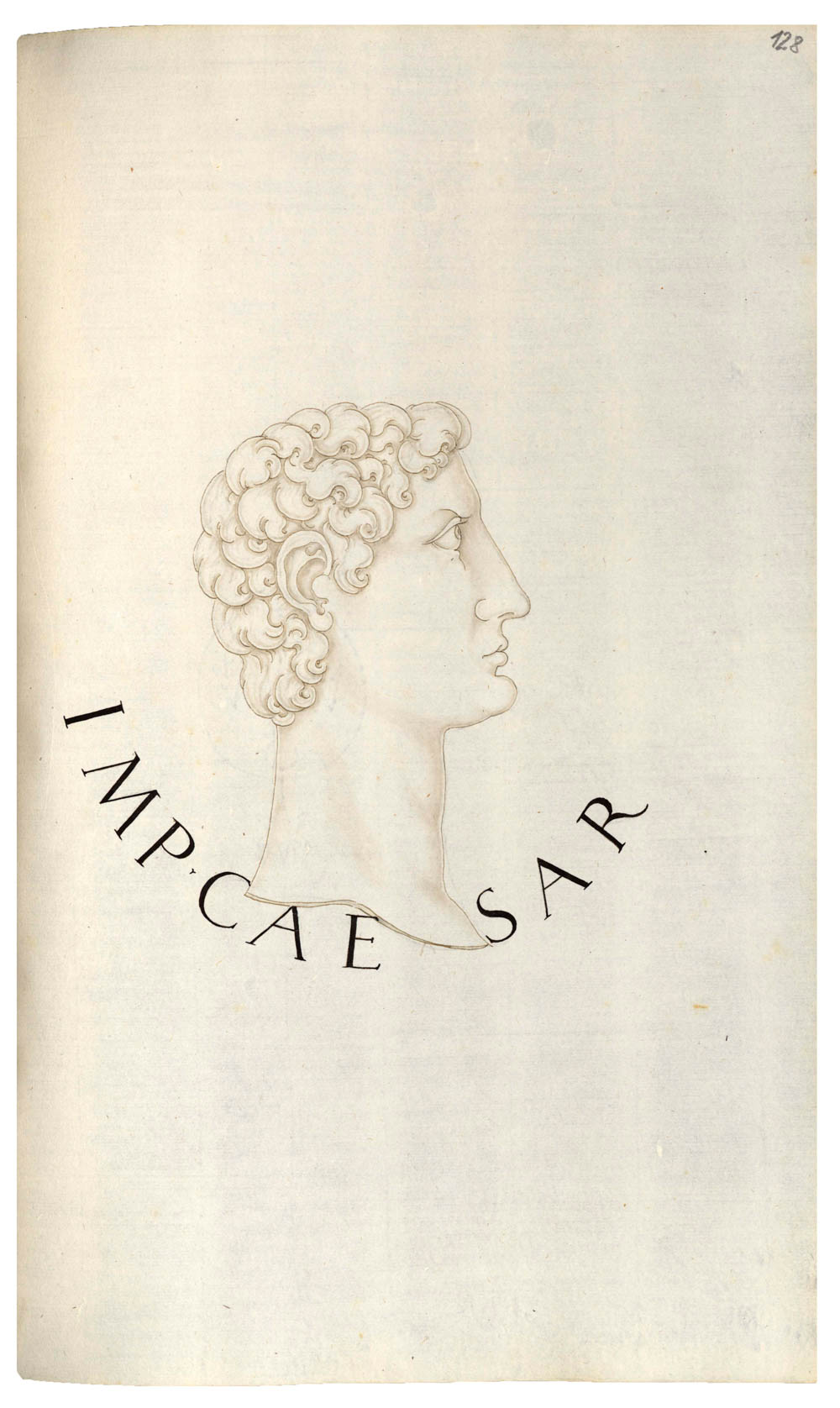

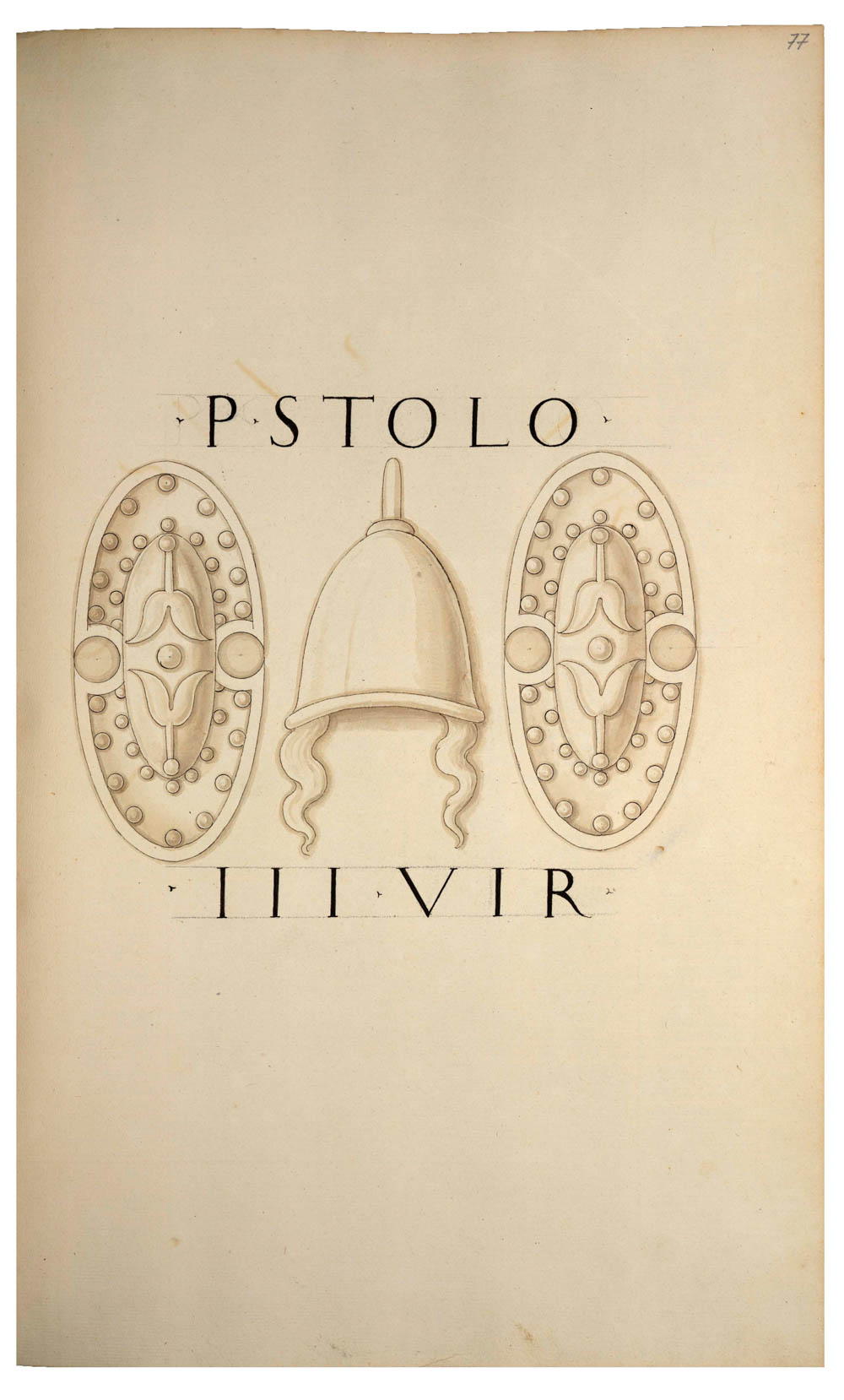

2.2 The second coin from this group is to be found on fol. 128r (fig. 9a: Augustus looking right, legend: IMP CAESAR) in the fourth volume and fol. 77r (fig. 9b: albogalerus between two shields, legend: P STOLO IIIVIR)[25] in the fifth volume of the MaNO. The description may be found in the second volume of the Diaskeué fol. 157r, no. 60. Achille Maffei, a Roman collector and antiquarian, is said to be the owner. Apart from Enea Vico (illustration of the reverse only)[26], Goltzius and Agustín depict it with the corresponding correct obverse[27].

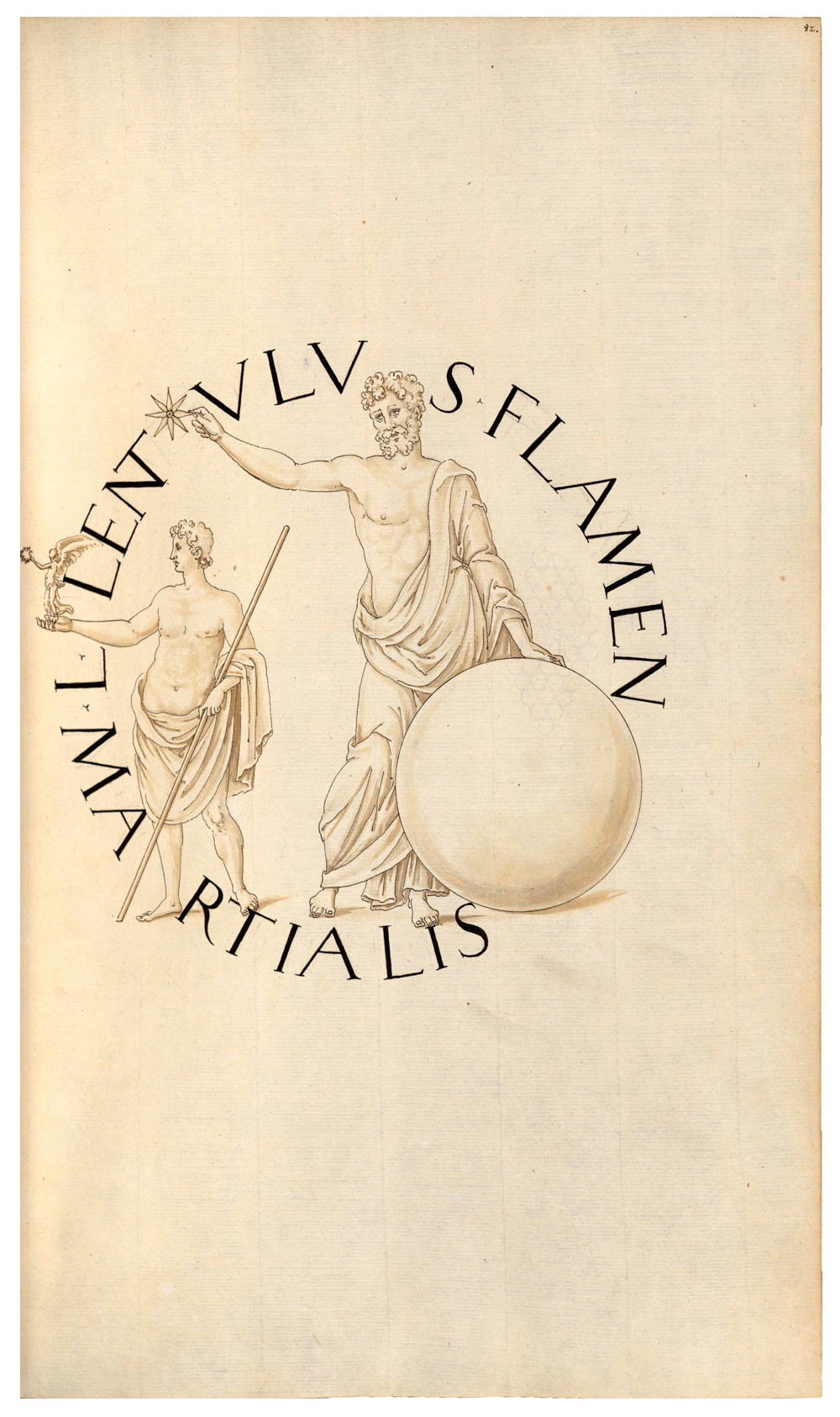

2.3

Of the third coin, only the reverse is shown on fol. 82r

(fig. 10: two togati, one resting on a shield, placing a

star on the other statue, which is holding a Victoria and spear,

legend: L LENTVLVS FLAMEN MARTIALIS)[28]

in the second volume of the MaNO. The

description of the entire coin is found in the Diaskeué

2, fol. 154v no. 48. Allegedly, this coin was in Strada’s own

collection. Enea Vico depicts only the reverse[29].

Goltzius and Ligorio reproduce it with the correct obverse in

their works[30],

Agustín and Erizzo omit it.

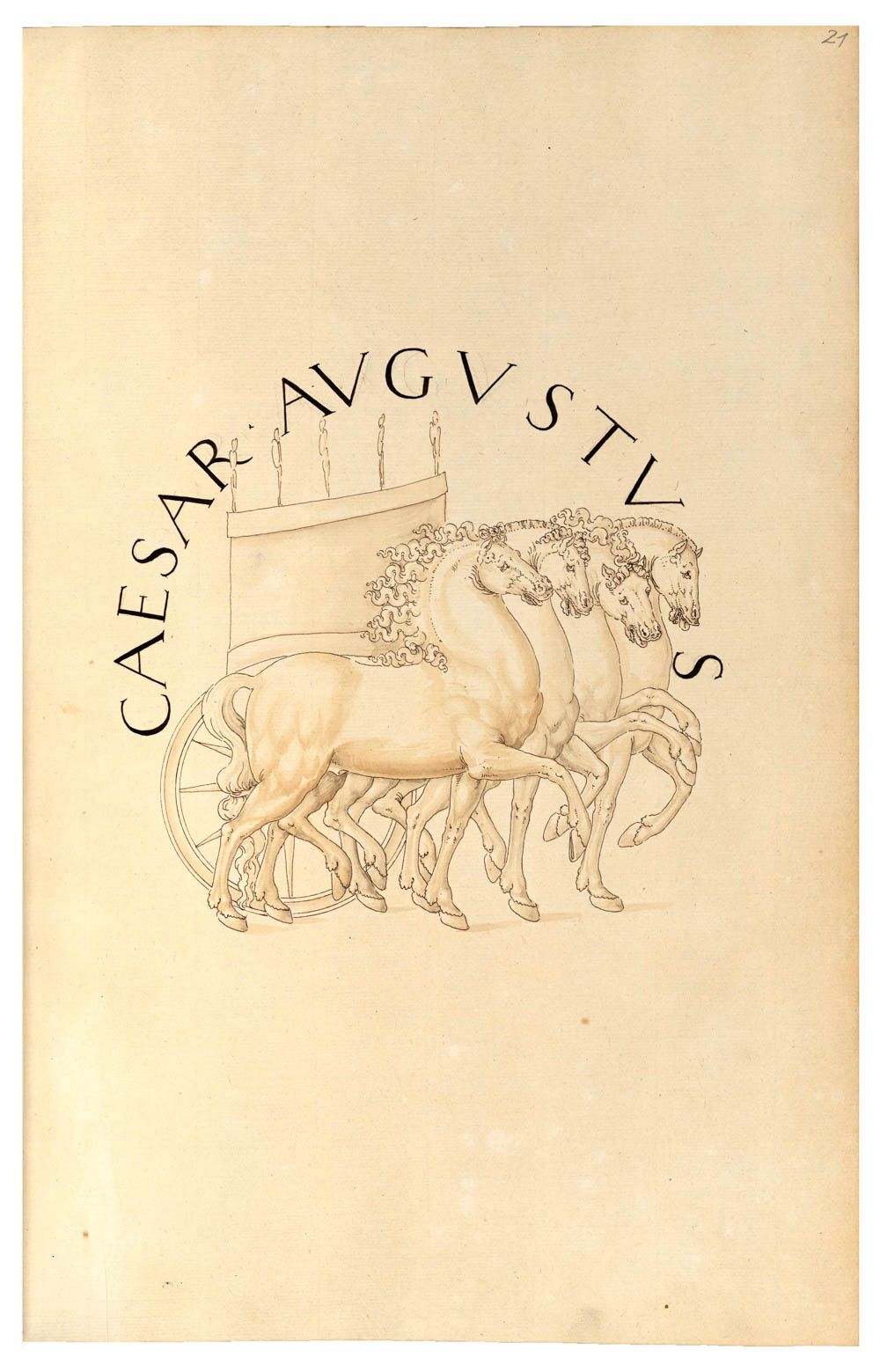

2.4

The fourth coin image – also merely depicting the reverse

– is to be found on fol. 21r (fig. 11a: quadriga with

statuettes, legend: CAESAR AVGVSTVS; b: denarius of

Augustus)[31]

in the fourth volume of the MaNO. The coin

is described in the second volume of the Diaskeué, fol.

154v no. 49. The description of the obverse says: Augustus

looking right, no legend is given. Again, Strada is named as the

owner. Vico also reproduces it with the missing abbreviation S C

in the legend[32]; i.e. he obviously copied the coin from Strada. None of the

above-mentioned antiquarians reproduced it.

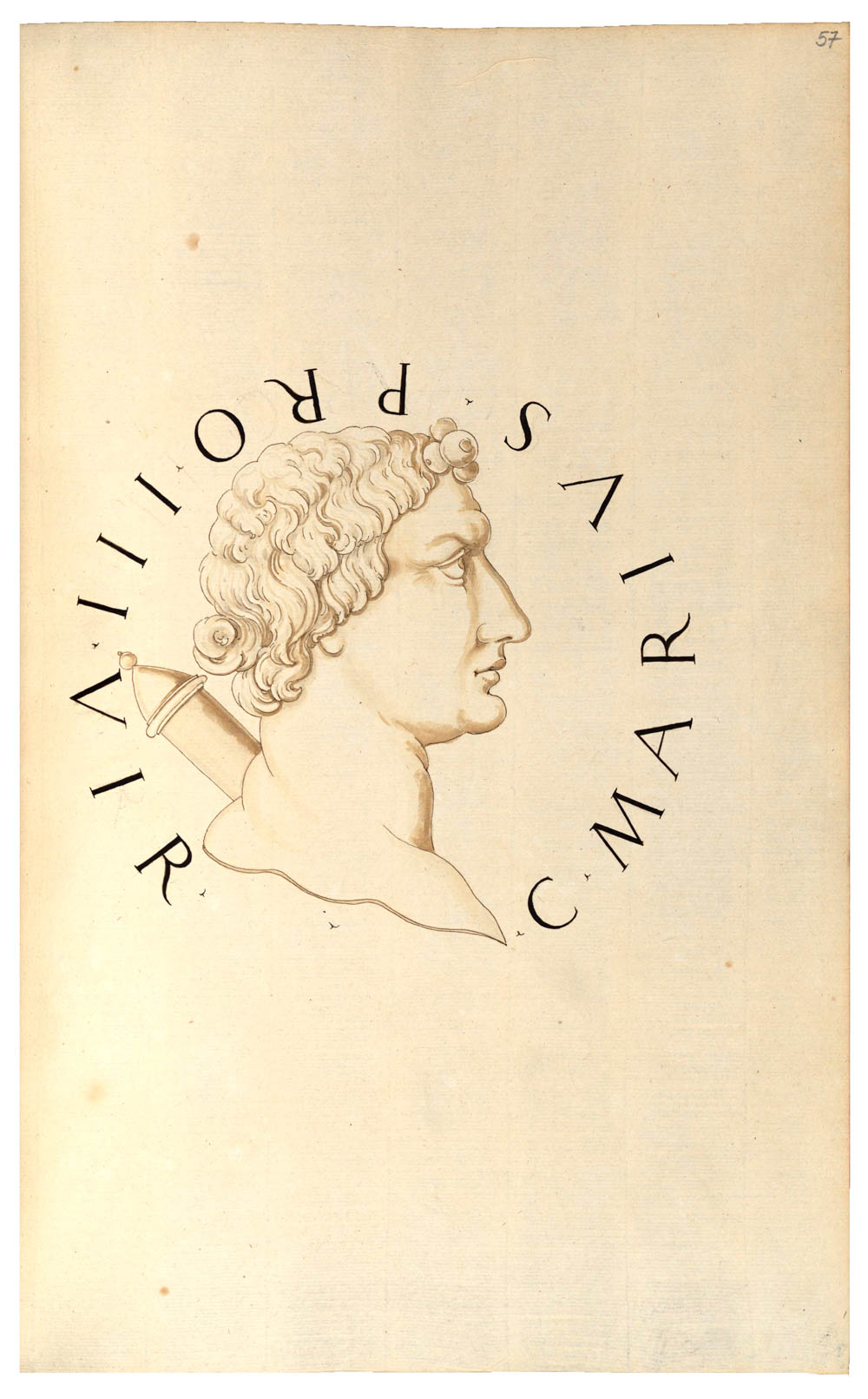

2.5

The fifth coin reverse – actually it is the obverse – can

be seen on fol. 57r in volume four of the MaNO (fig.

12a: Apollo with diadem and quiver, legend: C MARIVS PRO

IIIVIR)[33].

The description is in the second volume of the Diaskeué,

fol. 155r no. 50. The obverse is described as follows: Augustus

looking right, legend CAESAR AVGVSTVS. This piece also came from

Strada’s own collection. It was reproduced as a reverse by Vico[34].

The only other antiquarian to depict this coin is Goltzius (fig.

12b: Caesar Augustus pl. XXXI). He, as well, conceived it as

a reverse and combined it with another obverse[35]. The portrait is correctly recognized as that of Diana.

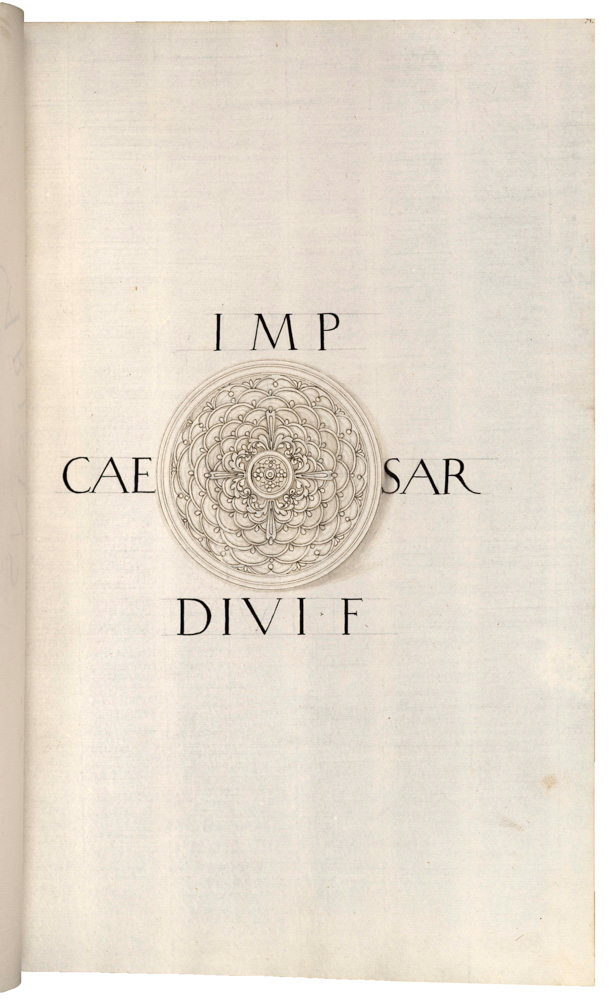

2.6

The reverse of the last coin in this category is

reproduced on fol. 71r (fig. 13: clypeus with gems,

legend: IMP CAESAR DIVI F)[36]

in the second volume of MaNO. The matching

description is listed in the second volume of the Diaskeué,

fol. 168r no. 115. The obverse is described as follows: Augustus

with helmet, looking right, without legend. Strada is mentioned

as the coin’s owner. In Vico only the reverse of the coin can be

found[37].

Erizzo reproduces it with the correct obverse[38];

so do Goltzius[39]

and Ligorio[40].

It is not included in Agustín.

The third group includes four coins:

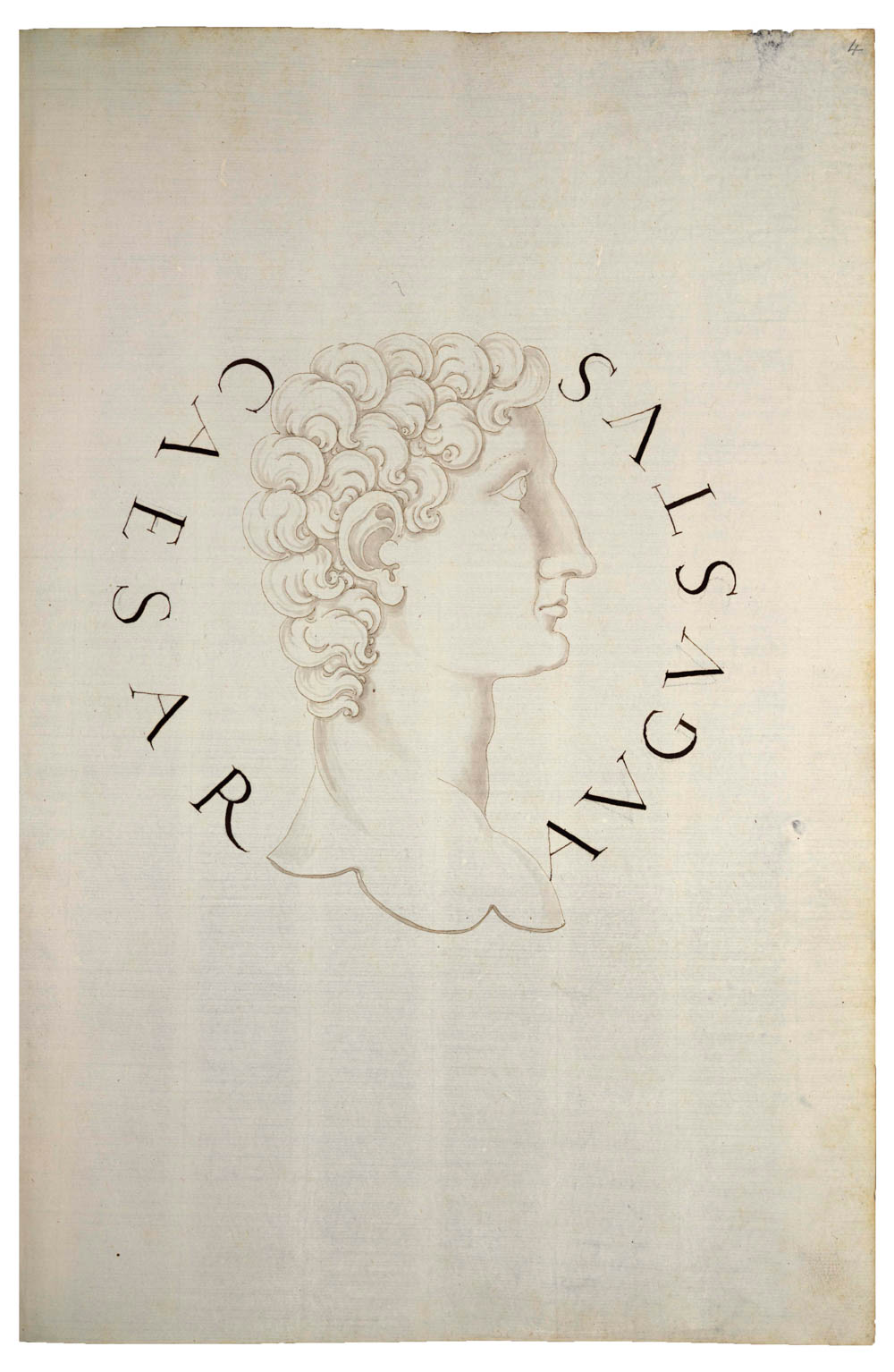

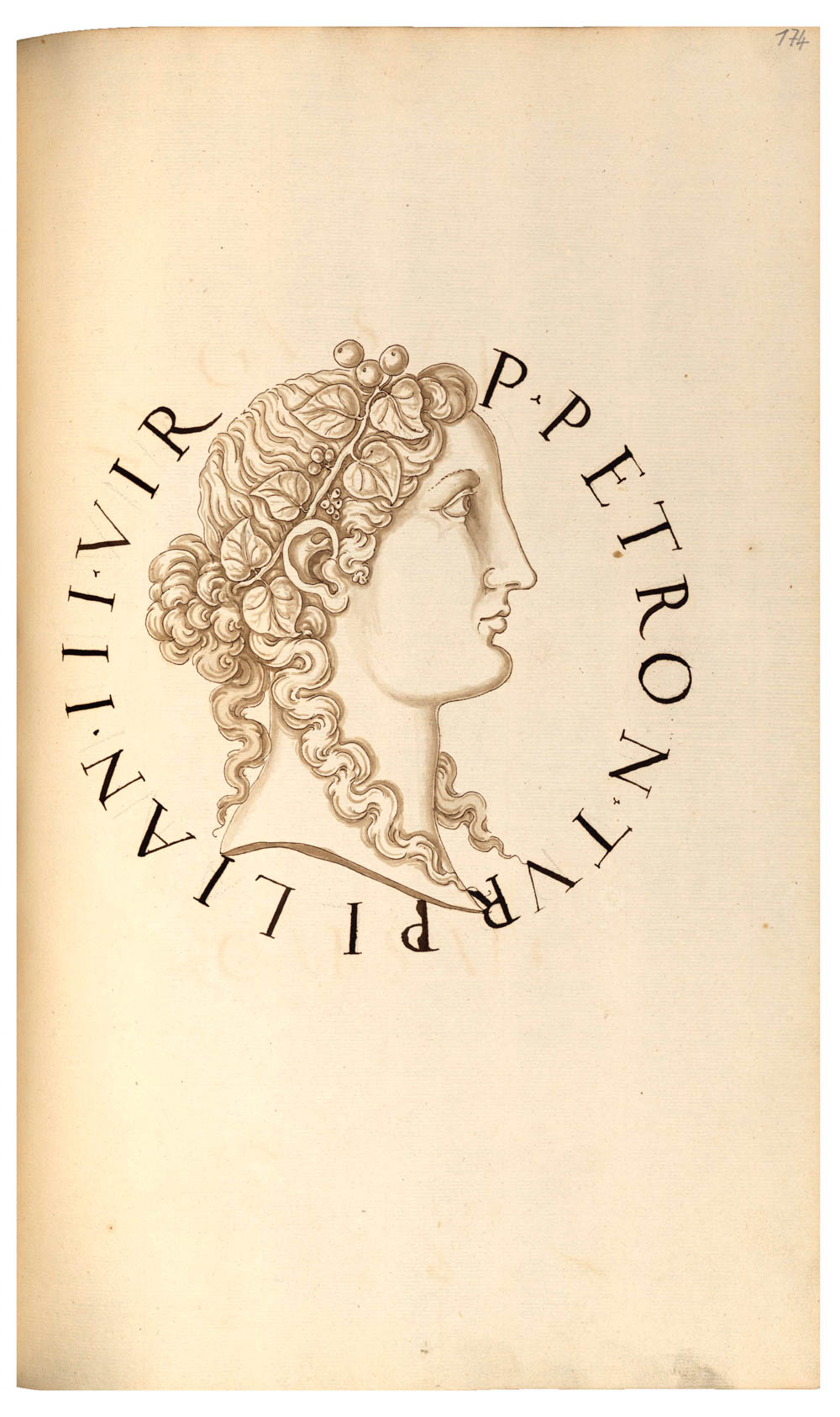

3.1

The first piece is included in the fifth volume of the

MaNO on fol. 4r (fig. 14a: Augustus looking right,

legend: CAESAR AVGVSTVS)[41]

and illustrated in the fourth volume of MaNO on fol. 174r

(fig. 14b: bust of Diana, legend: P PETRON TVRPILIANVS

IIIVIR)[42].

The description is found in volume two of the Diaskeué on

fol. 152 no. 34. It is presented as being in Strada’s

collection. In the MaNO fols. 174r and 175r (fig. 15a:

bust of Diana, legend: P PETRON TVRPILIANVS IIIVIR; b:

Augustus in elephant biga, legend: AVGVSTVS CAESAR)[43]

are correctly combined, i.e. fol. 174r is here correctly

presented as obverse and fol. 175r as reverse. This coin is

illustrated in Vico in the edition of 1554 i.e. Omnium

Caesarum; he mistook the obverse with the image of Diana for

the reverse, exactly as happened in Strada[44].

Goltzius, however, understood both sides of the coin described

by Strada as reverses[45].

Agustín and Erizzo did not reproduce this coin. Ligorio depicted

it correctly, as it was presented in the MaNO[46].

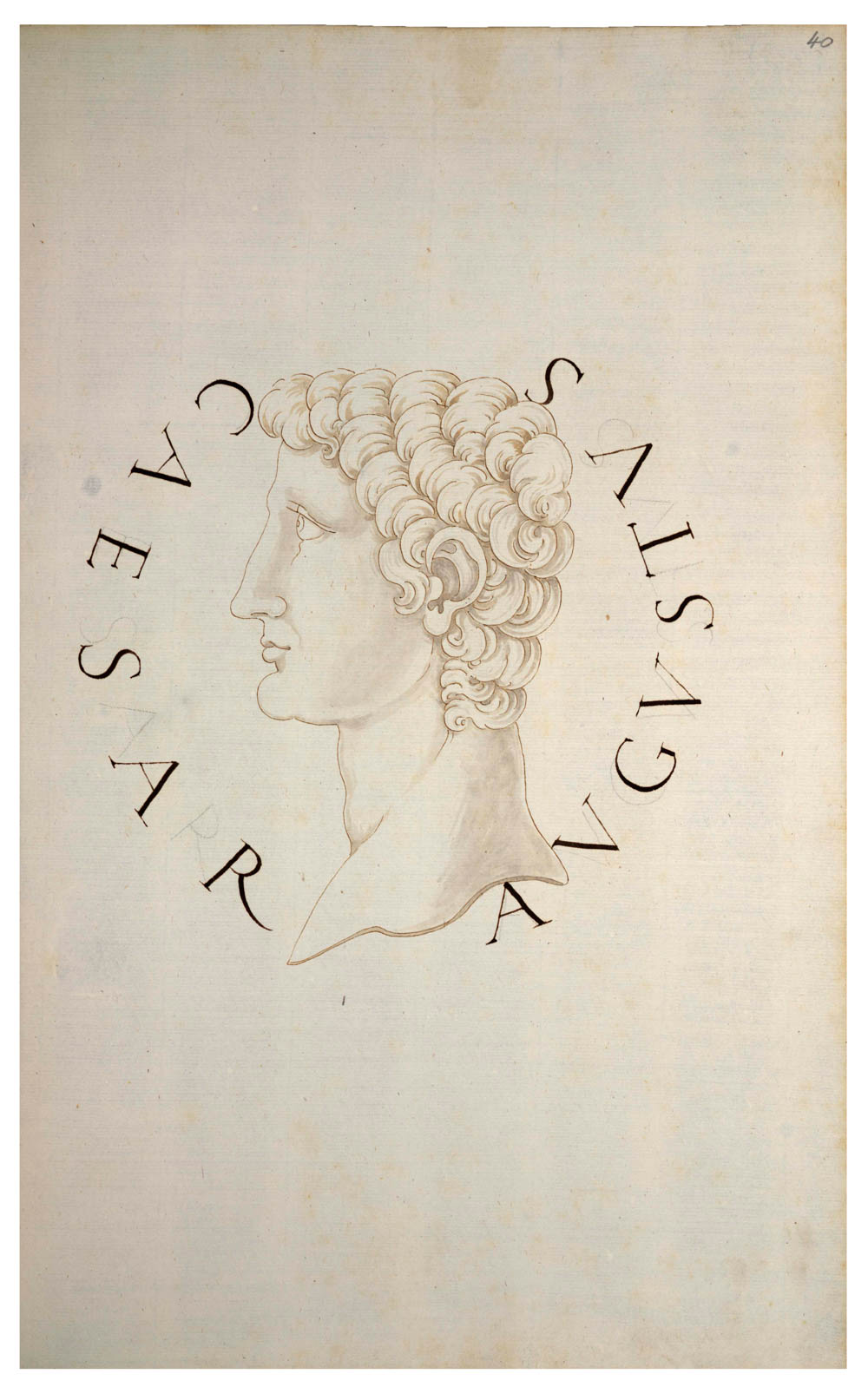

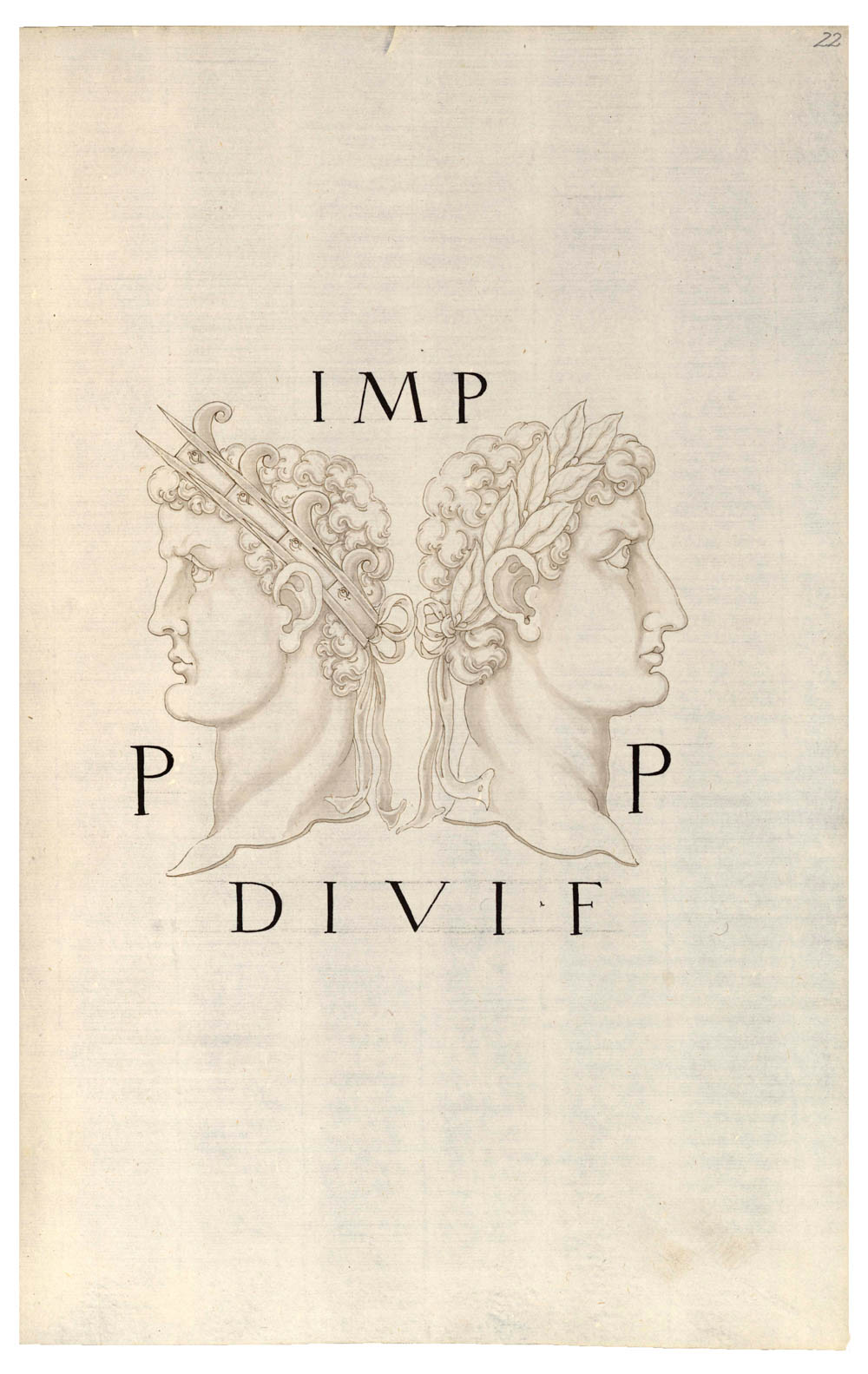

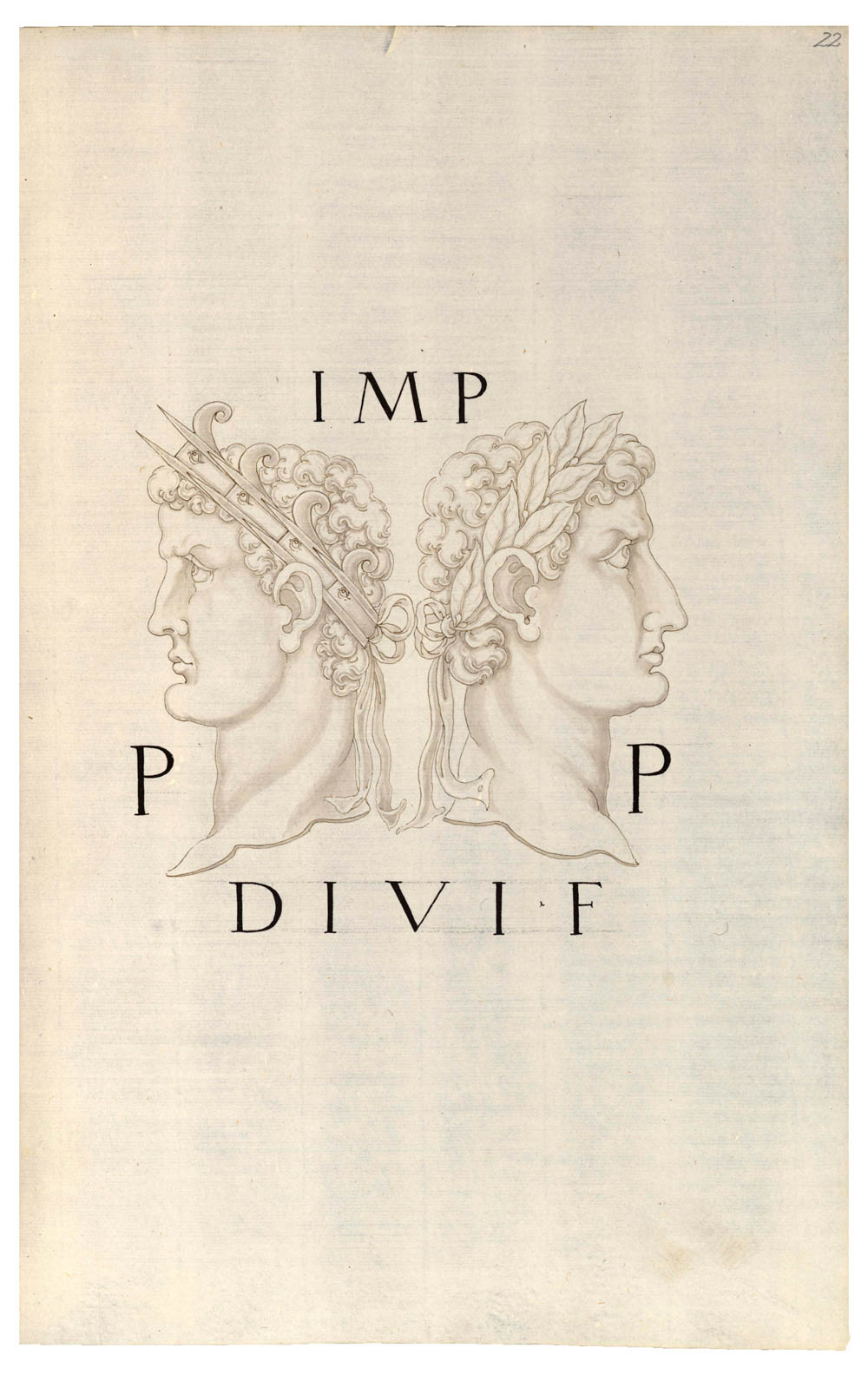

3.2

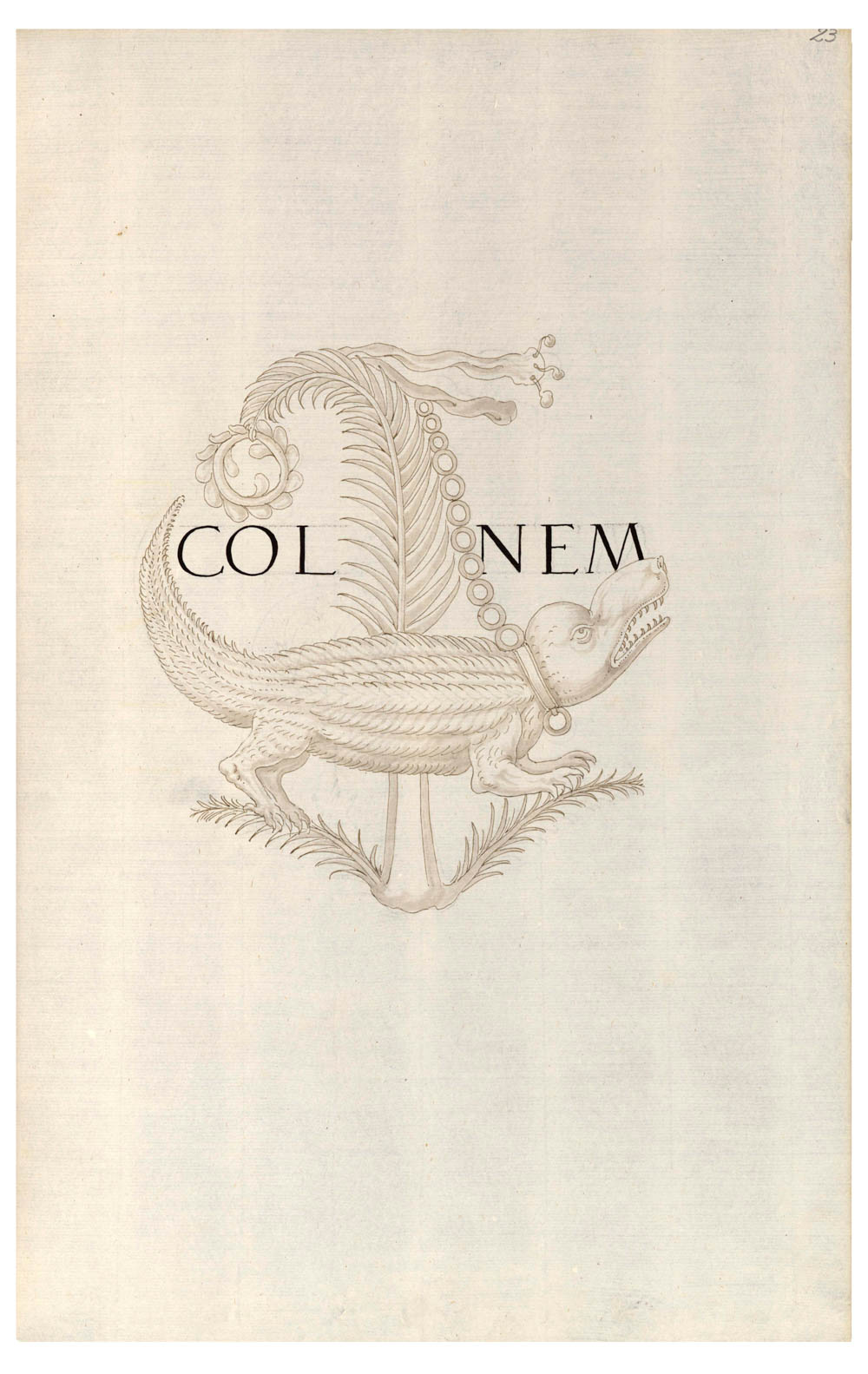

Strada confused the reverse with the obverse in the case

of the second coin – also included in the fifth volume of the

MaNO on fol. 40r (fig. 16a: Augustus looking left,

legend: CAESAR AVGVSTVS)[47]

and in the fourth volume on fol. 22r (fig. 16b: Antonius

and Lepidus, legend: IMP ...)[48].

It is described in the second volume of the Diaskeué,

fol. 152r no. 35. Strada was the owner of this coin. In the

Diaskeué, the coin on fol. 22r is described as reverse but

correctly linked in the MaNO as obverse to the following

coin illustration on fol. 23r (fig. 17a: Antonius and

Lepidus, legend on drawing: IMP P P DIVI F;

fig. 17b: Crocodile

in front of palm tree, legend: COL NEM)[49].

Vico depicts this reverse only in the 1554 edition of his book[50].

Sebastiano Erizzo, Hubertus Goltzius, Antonio Agustín and Pirro

Ligorio reproduce this coin with obverse and reverse correctly

linked as in the MaNO[51].

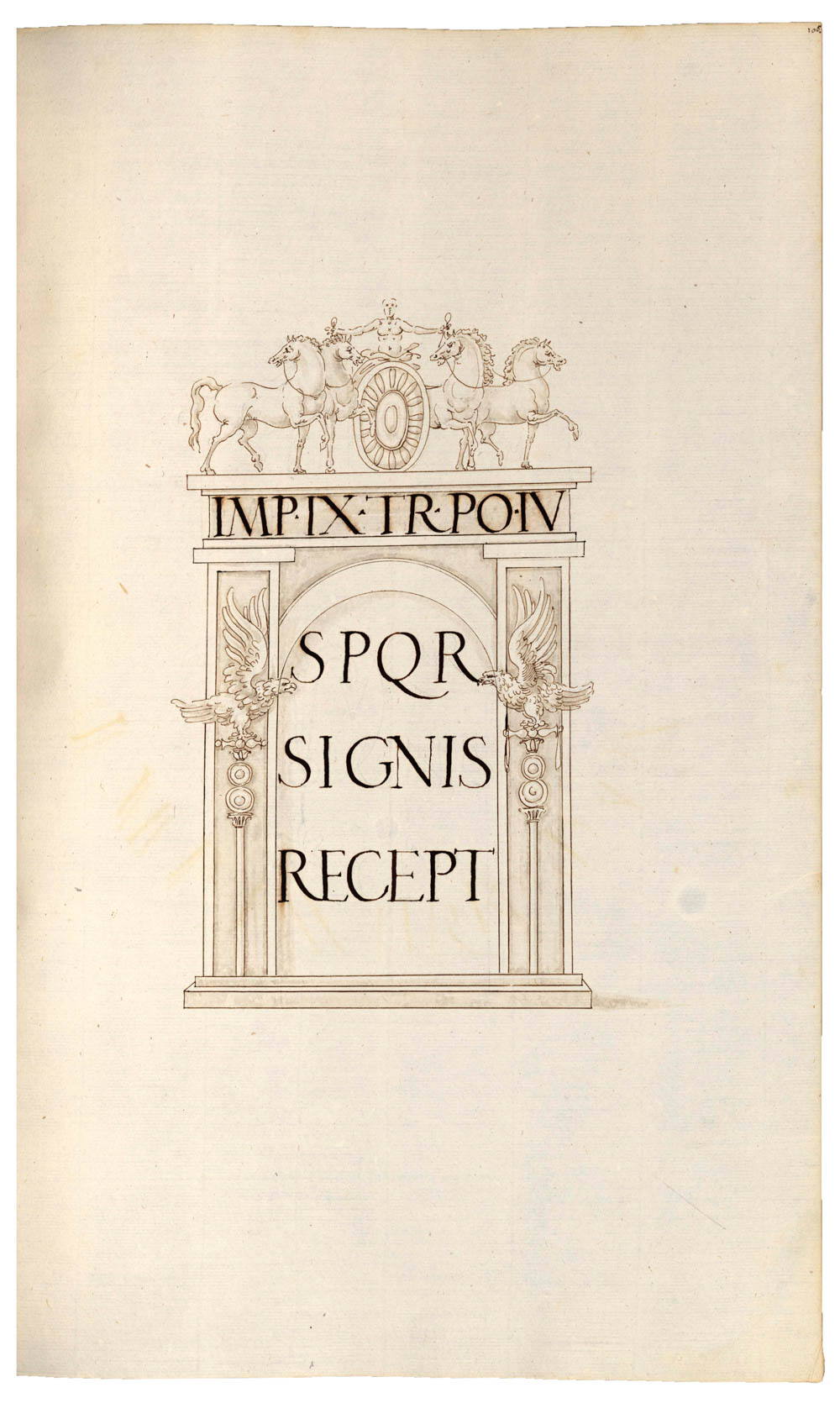

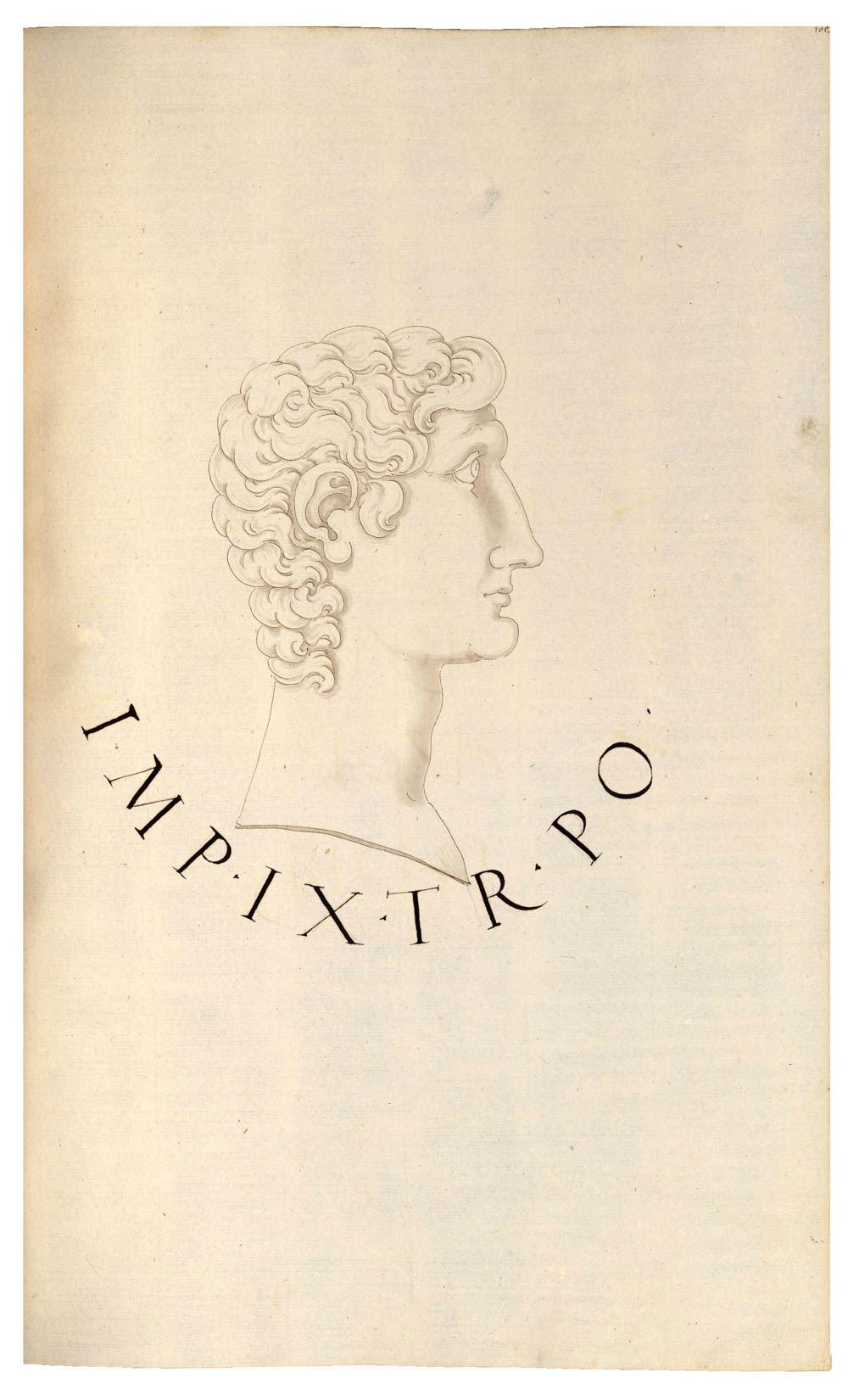

3.3

Of the third, non-existent coin, only the reverse is

shown in the MaNO in the second volume on fol. 106r (fig.

18a: arch of Augustus with quadriga, legend: IMP IX TR POT V

S P Q R SIGNIS RECEPTIS)[52].

The description can also be found in the second volume of the

Diaskeué on fol. 155r no. 51. The obverse is described but

not reproduced in the MaNO: Augustus looking right, no

legend is given. Again, Strada names Antonio Agustín as the

owner. The correct obverse can be found in the MaNO on

fol. 105r (fig. 18b: Augustus looking right, legend on

drawing: IMP IX TR PO)[53].

Vico also reproduces the arch[54].

It is not found in the works of Erizzo and Agustín. Goltzius

links it to an incorrect obverse[55].

Ligorio depicts the coin in the correct combination of obverse

and reverse[56].

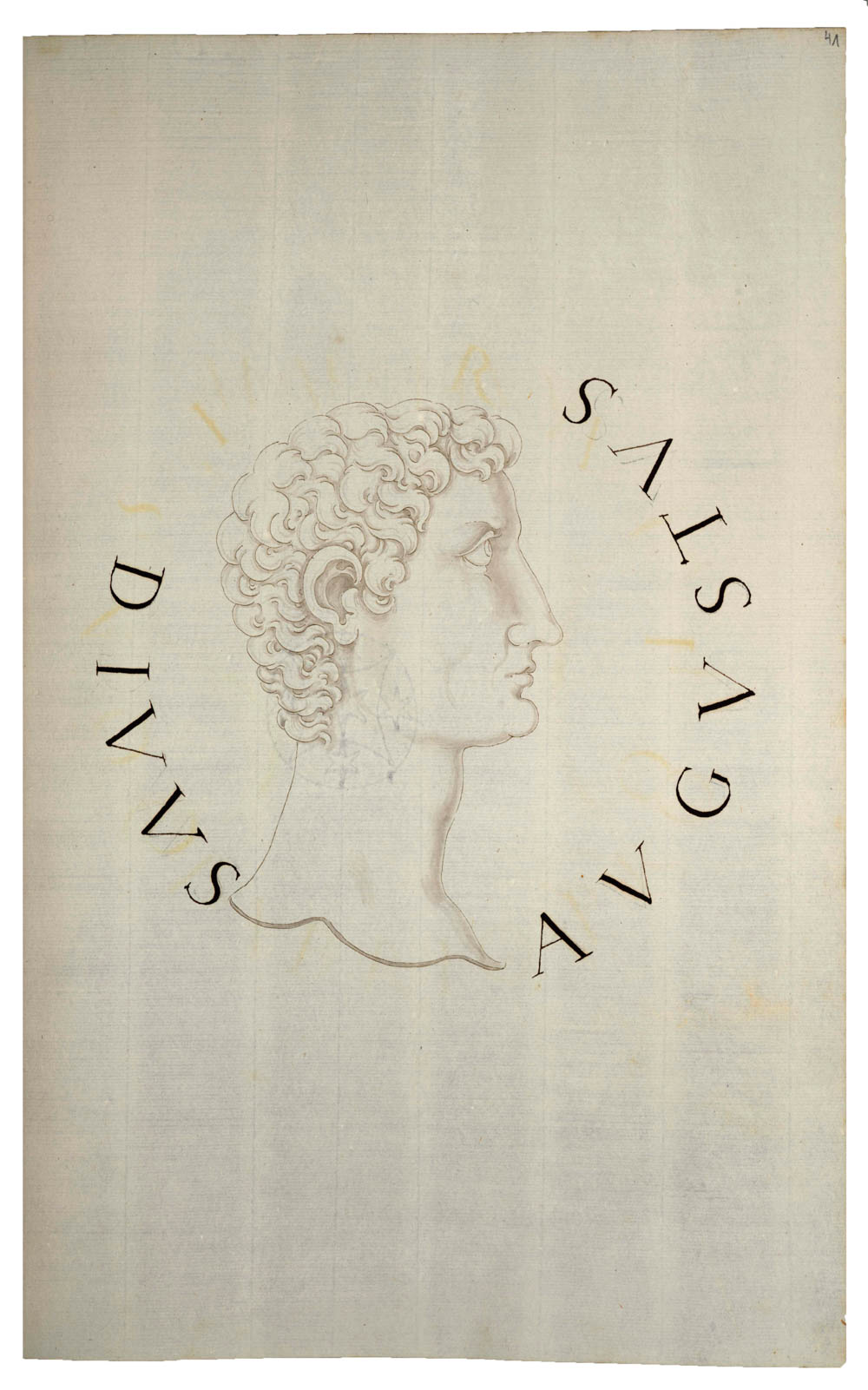

3.4

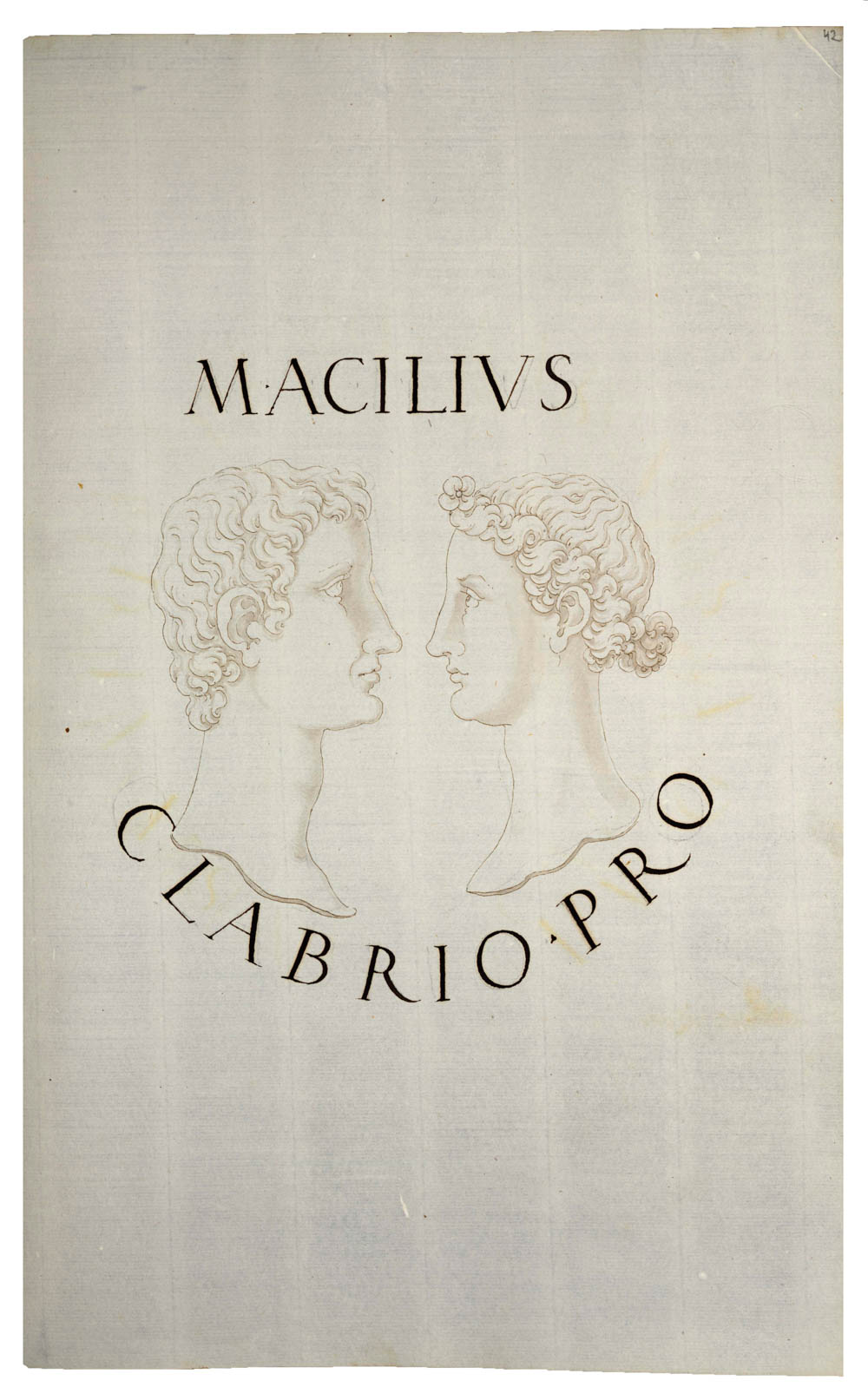

Of the fourth and last, unidentified coin, the obverse is

visible in the sixth volume of the MaNO on fol. 41r (fig.

19a: Augustus looking right, legend: DIVVS AVGVSTVS)[57],

while the reverse is depicted on fol. 42r (fig.

19b:

Augustus and Livia facing each other, legend: M ACILIVS GLABRIO

PRO)[58].

The coin is described in the second volume of the Diaskeué

on fol. 161r no. 81. It is said to have been in the collection

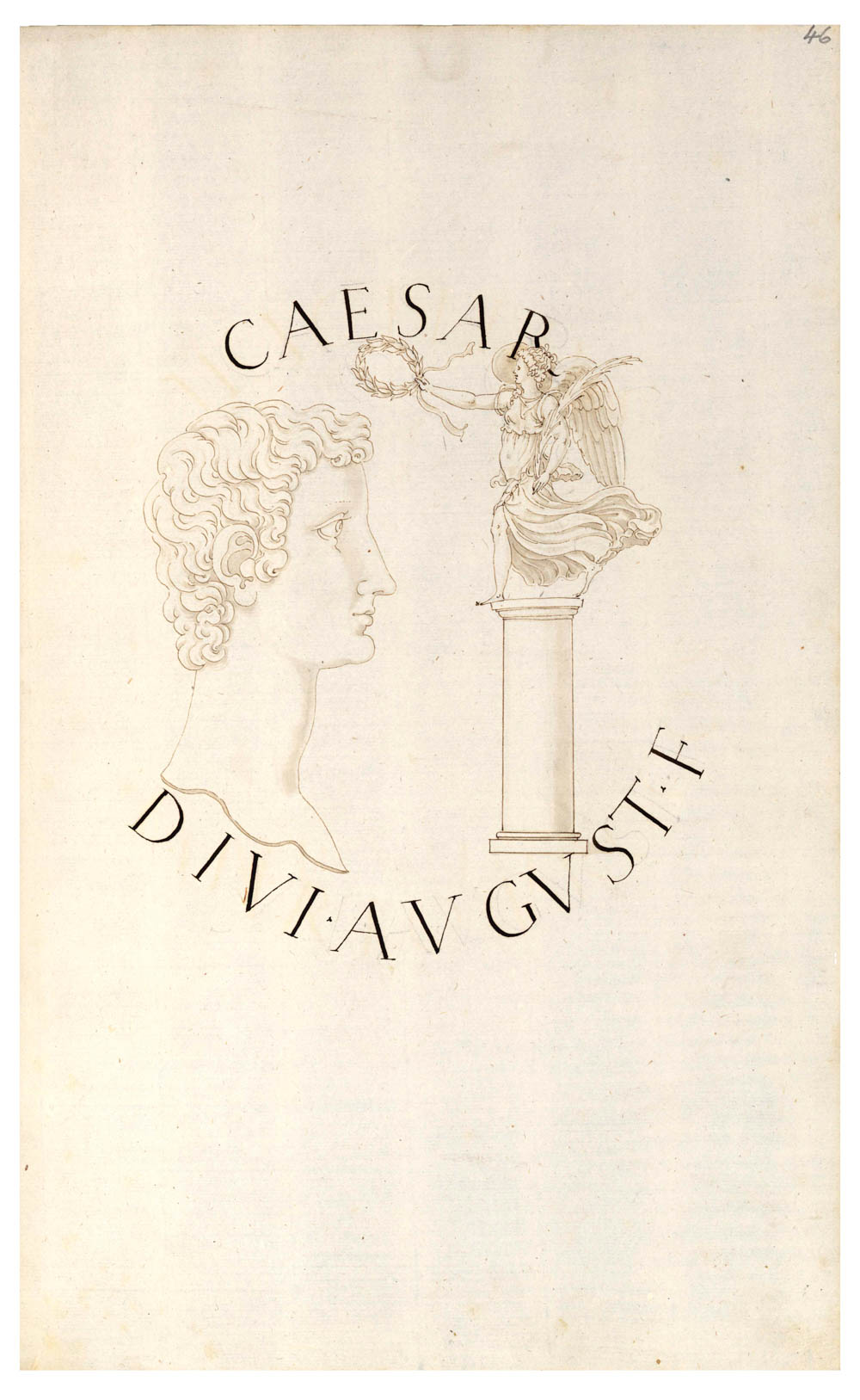

of Enea Vico. The correct obverse is found in volume four on

fol. 46r (fig. 20: Augustus looking right crowned by

Victoria on a column, legend on drawing: CAESAR DIVI AVGVST F)[59].

No other antiquarian reproduces this coin.

V. The following conclusions can be drawn from

this presentation:

Firstly, most of the

unidentifiable coins can be found in the collection of Jacopo

Strada, i.e. in the case of six coins out of 14. Whether these

coins were really in his collection, as claimed by Strada, can

unfortunately no longer be ascertained, since nothing is known

about the present whereabouts of his collections[60].

The three coins from

Antonio Agustín’s collection as well can no longer be

identified, since his collection was looted by Napoleon’s

troops. The illustrations in his 1587

Dialogos probably reproduce coins from Agustín’s own collection. The

coins described by Strada are however not among them[61].

Therefore, Strada’s information cannot be verified.

The coins from other

collections mentioned by Strada (Medici, Du Choul, Enea Vico,

Achille Maffei) can only be identified with difficulty[62].

Enea Vico adopted nearly

all the coins presented by Strada, i.e. ten out of 14.

Nonetheless, he depicted only the reverses, so that it cannot be

determined with certainty whether he used models from Strada.

Only in cases of inaccuracies in the reproductions in both

Strada and Vico, for example errors in the texts of legends

(here nos. 2.1 and 2.4), can we be sure that Strada

was used as model by Vico. Strada seems to have entertained a

lively exchange with him[63].

Nevertheless, he also regarded him as a great competitor, as he

stated in the preface to his Epitome[64].

Goltzius also was happy

to use Strada’s coin drawings as his source. Therefore, he

depicted three coins in his work as Strada had described them

(here nos. 1.2, 1.3, 2.5). His

presentation of the coins’ illustrations is clearly oriented on

Vico’s model; he was the first numismatist to adopt it[65].

Erizzo, however, only

adopted one coin from Strada (no. 1.2).

Neither Vico nor Goltzius or Erizzo specify

where they saw the depicted coins.

Agustín and Ligorio did

not reproduce any of Strada’s coins with incorrect die

combinations. All of them owned collections, of which Ligorio’s

was considered the most important at the time, according to

Goltzius[66].

Agustin’s was probably one of the largest, containing about

5,500 pieces[67].

Ligorio also visited a

great many coin collections in person. Therefore, in his

manuscripts he provides owner indications that are different

from those given in Strada’s works (e.g. in the case of no.

3.1). Here, Ligorio states a »cavalier Caro« as the owner of a

correctly reproduced coin, while Strada names his own collection

as repository of his invented coin.

Two of Strada’s

inventions were never accepted by other antiquarians (nos. 1.1

and 3.4). The first coin is said to have been in the Medici

collection, the other in the possession of Enea Vico. It is

therefore quite surprising that Vico did not illustrate a coin

from his own collection in his works. This fact could be another

indication that Strada’s information about the ownership of

coins is not necessarily accurate: As a consequence, for his

most imaginative coin inventions, such as the exemplars

depicting the assassination of Cicero, the depiction of the

temple of Janus with a four-headed Janus on the roof and a ship

with elephant prora in his works – in these cases in the

Epitome and Diaskeué – he named diverse owners

(assassination of Cicero) or referred to his own collection as

repository (temple of Janus and elephant prora)[68].

By stating the owner, he provided his inventions with a

›confirmed‹ authenticity. He hardly needed to fear verification

and exposure by his contemporaries, since at the time

communication channels were very slow and unreliable. Moreover,

only a few antiquarians other than himself undertook extended

journeys to visit foreign coin collections, as did Hubertus

Goltzius, for example[69].

Strada justifies his

inventions in the preface of the series with a statement

that »suitable coins have not yet been found

for all inscriptions – they have not yet been discovered –

although they were minted«[70].

Now he had ›found‹ them. His extensive

iconographic knowledge of ancient coins and of their legends

enabled him to do so. As a rule, he used really

existing coin dies and combined them with each other for the

coins presented in his works; as a result, they appeared all the

more credible to his contemporaries. Nonetheless, there were

some, such as Adolph Occo, who expressed doubts about the

authenticity of many coins presented by Strada, even though he

adopted several of Strada’s inventions[71].

Further in-depth investigations on volumes 9 (Nero), 11

(Vespasian) 16 (Antoninus Pius) and 17 (Marcus Aurelius) are

still to be undertaken. In these volumes, several combinations

of non-related obverses and reverses can be found. Many of his

inventions are included in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century

numismatic works and encyclopaedia, even in Occo’s works[72].

A complete and detailed investigation

of the complete set of coin inventions depicted in

the MaNO would be very helpful and important for the

history of numismatics; unfortunately, due to constraints of

time, this further investigation was impossible to achieve as

part of our project[73].

In conclusion, Strada’s

coin inventions as described in the Diaskeué provide

important further evidence that these coin descriptions were not

complementary to the illustrations in the MaNO, as he had

stated in the preface of his Commentary on Caesar[74]

and in the Index sive catalogus librorum, quos composuit aut

componi et scribi curavit aut denique alio modo comparavit[75],

but that these two works constituted two independent pieces of

writing.

Translation: Andrea M.

Gáldy

[1] For a

survey of these works: Heenes 2019, pp. 17–34.

[2] Also

see Heenes 2020, pp. 75–76.

[3]

A.A.A. NVMISMATΩN ANTIQVOR: ΔΙАΣKEYH.

HOC EST,

Chaldaeorum, Arabum, Libycorum, Græcorum, Hetruscorum,

ac Macedoniæ, Asæ, Syriae, Ægypti, Syculorum, Latinorum,

seu Romanorum Regum, a primordio Vrbis, Deûm, Coss.

tempore Reipub: & crescente adhuc, tam sub Cæss.

Latinis, in occidente, quam Græcis Impp. in oriente,

declinante Imperio P.R. denique Hexarchorum, Barbarorum

Principum, Ducumuè: METALLICARVM EICONVM explicatio. Ex

Musæo IACOBI STRADÆ Mantuani Antiquarij, Ciuis Romani:

Cum septem Indicibus Locupletissimis, partim

Alphabeticis, quibus res diuersissimæ continentur,

partim serierum, quæ Regum, Cæss. Impp. ac Tyrannorum,

necnon Heroinarum nomina perscribunt.

[4]

MAGNVM AC NOVVM OPVS

Continens descriptionem Vitae imaginum, numismatum

omnium tam Orientalium quam Occidentalium Imperatorum ac

Tyrannorum, cum collegis coniugibus liberisque suis,

usque ad Carolu(m) V. Imperatorem.

A Iacobo de Strada Mantuano elaboratum.

TOMVS PRIMVS. ANNO DOMINI MDL.

[5]

Dialoghi,

p. 117: »My friend Pirro Ligorio from Naples, a great

antiquarian and painter, has written over forty books

[i.e. manuscripts] about coins, buildings and other

things [...] without really mastering Latin, as did

Hubertus Goltzius, Enea Vico, Jacopo Strada and others.

Those who read their books might think that they have

read all the Latin and Greek books ever written. They

took what they needed from others and they drew exactly

with the pencil what others described«.

See chapter 7 on »Strada’s Numismatic

Method« in the forthcoming publication of our research

results: Jacopo Strada’s Magnum ac Novum Opus: A

Sixteenth-Century Numismatic Corpus (CYRIACUS.

Studien zur Rezeption der Antike 16); in what follows

the title is abbreviated to Heenes – Jansen

(forthcoming).

[6] See

Dekesel 1995, pp. 210–222.

Cunnally 2016, p. 6, even speaks of a »Renaissance

nummomania« current at the time.

In my essay I cite Erizzo’s edition

of 1585–1590 (Varisco – Paganini), in what follows

abbreviated as Discorso 1585–1590, since it is

the most comprehensive. I would like to thank Ginette

Vagenheim for making me aware of the differences between

the individual editions of Erizzo’s works. On the single

Erizzo editions, see: Peter 2013, pp. 159–177.

[7]

Vienna University Library,

Sig. III-160.898/2.

[8] After

the figure numbers, Strada’s interpretation and the coin

legends in the Diaskeué are briefly mentioned.

[9]

MaNO 4,

fol. 196r (CensusID

10174940); fol. 197r (CensusID

10174944).

[10]

MaNO, 4

fol. 188r (CensusID

10175427); fol. 189r (CensusID

10175431).

[11]

Caesar Augustus,

Taf. XLVII Nr. XV (CensusID

10155427, no individual

identifications), there linked to pl. X no. 109,

correct, Augustus is however turned to the right.

[12]Erizzo,

Discorso 1585–1590,

p. 41.

This illustration is not found in the first edition of

the work but only in the edition published by Varisco –

Paganini in the years 1585‒1590, which appeared after

Erizzo’s death. It is therefore very likely that it was

added by Varisco – Paganini without the author’s

knowledge. It is possible that their source had been

Strada.

[13]

Discorsi,

p. 55 (CensusID 10068763). It can be

found in the edition of 1555.

[14]

MaNO 4,

fol. 258r; MaNO 4,

fol. 259r (CensusID

10175892).

[15] Cf.

chapter 5 »Strada’s Numismatic Works« in Heenes – Jansen

(forthcoming).

[16]

Caesar Augustus,

pl. LVII no. III (CensusID

10155538, no individual

identifications) is paired with the correct obverse:

Taf. VIII Nr. 88 (CensusID

10153859, no individual

identification).

[17]

MaNO 5,

fol. 204r (CensusID

10174588); fol. 203r (CensusID

10176387).

[18]

Omnium Caesarum,

pl. BBVII no. 78 (CensusID

10024666).

[20]

MaNO 4, fol.

213r (CensusID

10174114).

[22]

Caesar Augustus,

pl. XXXVI no. XIIII (CensusID

10158136).

[23]

Caesar Augustus,

pl. IX no. 114 (CensusID

10158132).

[24]

AST 21, p. 100, fol. 73r nos. 740 & 741.

[25]

MaNO 4 fol.

128r (CensusID

10173645); MaNO 5 fol.

77r (CensusID

10174982).

[26]

Omnium Caesarum,

pl. BBI no. 9, Le imagini,

pl. 14r I (CensusID

10028315).

[27]

Caesar Augustus,

pl. LXXIII no. XXI

(reverse

CensusID 10157765),

correctly linked to pl. XIII no. 153 (obverse

CensusID 10157761);

in Agostin’s Dialoghi, p. 153, it is

paired with another, potentially correct obverse (CensusID

10031255).

[28]

MaNO 2, fol.

82r (CensusID

10171672).

[29]

Omnium Caesarum,

pl. BBVI no. 67

CensusID 10024694;

Le imagini, fol. 16v G (CensusID

10029707).

[30]

Caesar Augustus, pl. IX no.

101, pl. LXXII no. XI (CensusID’s

10157598 +

10157602);

AST 21, p. 100 fol. 73r nos. 742 & 743.

[31]

MaNO 4, fol.

21r (CensusID

10174767).

[32]

Le imagini,

fol 17 A (CensusID

10029756); Omnium Caesarum,

pl. BBVII no. 73 (CensusID

10024655).

[33]

MaNO 4, fol.

57 (CensusID

10174779).

[34]

Le imagini,

fol. 16v H (CensusID

10029710); Omnium Caesarum,

pl. BBVI no. 68 (CensusID

10024696).

[35]

Caesar Augustus,

pl. XXXI no. XXX (CensusID

10153994, no individual

identification). The obverse pl. II no. 22 is not

correct (CensusID

10153824, also without

individual identification). The correct reverse is

depicted on pl. IX no. 104 (CensusID

10158132).

[36]

MaNO 5, fol.

115r (CensusID

10176610).

[37]

Le imagini,

fol. 14v A (CensusID

10028377),

Omnium Caesarum,

pl. BBII no. 13.

[38]

Discorso

1585–1590, p. 24 (CensusID

10013376).

[39]

Caesar Augustus,

pl. LXXIII no. XV (CensusID

10157620) with the correct

obverse pl. IIII no. 39 (CensusID

10157613).

[40] AST 21,

p. 92 fol. 67v nos. 669 & 670.

[41]

MaNO 5, fol.

4r (CensusID

10174368).

[42]

MaNO 4, fol.

174r (CensusID

10174374).

[43]

MaNO 4, fol.

175r (CensusID

10176979).

[44]

Omnium Caesarum,

pl. BBVIII no. 88 (CensusID

10018390).

[45]

Caesar Augustus,

pl. XXXVII no. XXXII (CensusID

10224548) and no. XXXIII (CensusID

10158706).

[46] AST

21, p. 63 fol. 47r no. 410 and 411.

[47]

MaNO 5, fol.

40r (CensusID

10174606).

[48]

MaNO 4, fol

22r (CensusID

10174609).

[49] MaNO

4, fol. 23r (CensusID

10224478).

[51]

Discorso

1585-1590, p. 6; Caesar

Augustus, pl. XLIX no. II and pl. IIII no. 45 (CensusID

10155450; no individual

identification); Dialoghi, p. 191 (CensusID

10018368); AST 21, p. 68 fol.

50r no. 457 and 458.

[52]

MaNO 2, fol.

106r (CensusID

10173659).

[53]

MaNO 2, fol.

105r (CensusID

10173661).

[54]

Le imagini,

fol. 15v H (CensusID

10029437),

Omnium Caesarum,

pl. BBIIII no. 44.

[55]

Caesar Augustus,

pl. XXXIX no. XIIII is not paired with the correct

obverse, i.e. pl. XIII no. 149. The correct obverse can

be found in Caesar Augustus pl.

XIIII no. 160 (CensusID

10153770).

[56] AST 21,

p. 84 fol. 60r nos. 556 & 557.

[58]

MaNO 6, fol.

42r (CensusID

10178086).

[59]

MaNO 4, fol.

46r (CensusID

10224588).

[60] The

projected sale of his collection to Wilhelm von

Rosenberg and Elector August of Saxony did not come off.

After Strada’s death, the collection was »scattered to

the winds«; Lietzmann 1997, pp. 384–385; 387–388; 394.

Dirk Jacob Jansen provided this information on 5 March

2021.

[61]

Agustín bequeathed his coin collection to the Spanish

King. It included 130 gold coins, 1,400

coins in silver and 3,871 in bronze. The

bronze coins were taken to the coin cabinet at the

monastery San Lorenzo de El Escorial. From there, they

were stolen by Napoleon’s troops; their present location

is unknown. In the original edition (Dialogos)

only 292 coins are depicted on 52 plates. These probably

come from Agustín’s collection (information provided by

Paloma Otero, Museo Arqueológico Nacional, Madrid and

Mariano Carbonell, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona).

[62] My

request for information about the coin from the Medici

collection could not be answered, since during the past

three years no new curator has been appointed for the

department of ancient coins at the Archaeological

Museum, Florence; information provided by Mario Iozzo on

5 March 2021. Nothing is known about the whereabouts of

the collections of Achille Maffei, Francesco Venier and

Enea Vico; information provided by Federica Missere

Fontana on 6 March 2021. On sixteenth-century coin

collectors, cf. Missere Fontana 1994, pp. 343–383: on

Francesco de Medici, see pp. 350–351; Achille Maffei pp.

358–359; Francesco Venier pp. 367–368; Enea Vico pp.

368–370. There also seems to be no information on the

present whereabouts of the collection of Du Chouls.

Unfortunately, my two inquiries addressed to Jean

Guillemain remained without answer.

[63]

Missere Fontana 1994, p. 364.

[64]

Colophon of the Epitome, p. A

4r.

[65] Lemburg-Ruppelt

1988, p. 167.

[66] Peter 2009, p. 123.

[67] See

note. 66.

[68] Also

see Heenes 2020, pp. 59–65 (DOI

10.17879/ozean-2020-2914).

[69] On

Strada’s travels, see my chapter »Strada’s Numismatic

Works« in the publication of our project. Hubertus

Goltzius undertook two long journeys, during the first

of which he visited 799 Münzsammlungen; see Dekesel

1988, p. 7.

[70]

Series,

fol. 1r.

[71] See

the following note.

Introductio, p. 188 cites

Charles Patin Adolf Occo’s statement about the volumes

at Gotha: »... ibidem miraberis sane et nummorum

varietatem et sumptuum gravitatem: sed omnio puto multos

esse appictos qui non sunt in reum natura.

Thesaurus est pretiosus et Principe

dignus«; von Busch 1973, p. 348, note 141.

[72] E.g.

Diaskeué 4, fol. 15r, p. 667, no. 7 for

MaNO

14, fol. 24r (palace of

Nerva) in: Imperatorum,

p. 146; Diaskeué 4,

fol. 33r, p. 703, no. 51 for

MaNO

14, fol. 112r (Imperator

on horseback, in the foreground the river god Nile with

hippopotamus) in:

Diccionario, vol. 5, p. 261;

Diaskeué 4, fol. 46v, p. 730, no. 86 for

MaNO

14, fol. 158r (city walls

of Selinunt) in:

Lexicon universae,

vol. 4, 1, col. 1581;

Diaskeué 4, fol. 72r, p. 781, no. 180 with

MaNO

14, fol. 172r (cityscape

of Babylon) in:

Lexicon universae,

vol. 5, 1, col. 1486. Most

recently Woytek – Williams

2020, p. 296 on two inventions of coin types that are

also to be found in Occo’s edition Imperatorum.

[74]

C. Iulii Caesaris,

Dedicatoria.

[75]

Index,

fol. 1v. This is a list of

books that Strada had yet to publish; for the complete

list, see Jansen 2019, pp. 902–914.