Two gold medallions of the Apostolo Zeno Collection in the British Museum*

Abstract:

The paper aims to reconstruct the purchase, sale and current

location of some gold medallions acquired by the Venetian

erudite and collector Apostolo Zeno. In particular, there were

four specimens that Zeno sold to cardinal Alessandro Albani,

which later became part of the Vatican collection. Two of these

medallions were later bought by the Duke of Blacas and then

passed into the collection of the British Museum, where they are

currently kept.

Keywords:

Apostolo Zeno (http://viaf.org/viaf/14779941;

http://d-nb.info/gnd/116980257);

Gold Medallions; Cardinal

Alessandro Albani (https://viaf.org/viaf/34465260/;

http://d-nb.info/gnd/119212064);

Louis, Duke of Blacas (http://viaf.org/viaf/41979936;

http://d-nb.info/gnd/1050400712);

British Museum.

Zusammenfassung: Ziel dieses Beitrags ist es, den Verbleib einiger Goldmedaillons aus dem Besitz des venezianischen Gelehrten und Sammlers Apostolo Zeno zu rekonstruieren: Vier Exemplare, die Zeno an den Kardinal Alessandro Albani verkauft hatte, gelangten schließlich in die Vatikanischen Museen. Zwei dieser Medaillons wurden später von Louis, Duc de Blacas d’Aulps erworben und befinden sich heute im Münzkabinett des British Museum.

Schlagwörter: Apostolo Zeno; Gold-Medaillons; Kardinal Alessandro Albani; Louis, Duc de Blacas d’Aulps; British Museum.On 12 September 1718 the

Venetian erudite Apostolo Zeno (1668–1750) arrived in Vienna, at

the court of the Emperor Charles VI of Habsburg (1711–1740)

where he remained, more or less permanently, until

1731, and where he devoted himself, from 1722 with increasing

assiduity and constancy, to the collection and the study of

ancient coins. As a result, an extraordinary collection of over

ten thousand pieces was achieved thanks to

the considerable wealth provided by his

service, as poet laureate, at the imperial court and to

the network of relationships he built and

maintained throughout his life.

Especially during the

first years in Vienna, Zeno had the opportunity to purchase some

gold medallions that soon, however, he decided to sell in order

to realise a significant profit, as confirmed by a passage in

the »Diario Zeniano«[1],

dated on 31 July 1745: »Una volta sola so d’aver venduto

medaglie[2]:

e furono quattro medaglioni d’oro, che diedi all’Albani per 170

zecchini: a me costavano 25 ongari«[3].

Albani has to be identified with the Catholic cardinal

Alessandro Albani (1692–1779), born in Urbino, collector of

antiquities and art patron.

Zeno

came into possession of the four specimens in different times

and circumstances. One of these medallions,

minted during the reign of Gallienus (253–268 A.D.), was

purchased between August and September 1723, when he was in

Prague for the coronation of Charles VI as King of Bohemia, and

he had the opportunity to acquire the precious specimen, as

testified by what he wrote to his half-brother Andrea Cornaro on

14 September 1723: »I giorni passati comperai qui un altro

bel medaglione d’oro di peso di quattro ungheri, con la

testa di Gallieno da una parte, e dall’altra con un Ercole con

clava, e pelle di lione, e la leggenda Virtus Gallieni Augusti«[4].

Zeno’s mention to »un altro bel medaglione d’oro«

is indirectly alluding to the first medallion, struck by Valens

(364–378 A.D.), that the Count Lippe gave to him two years

earlier in Vienna[5].

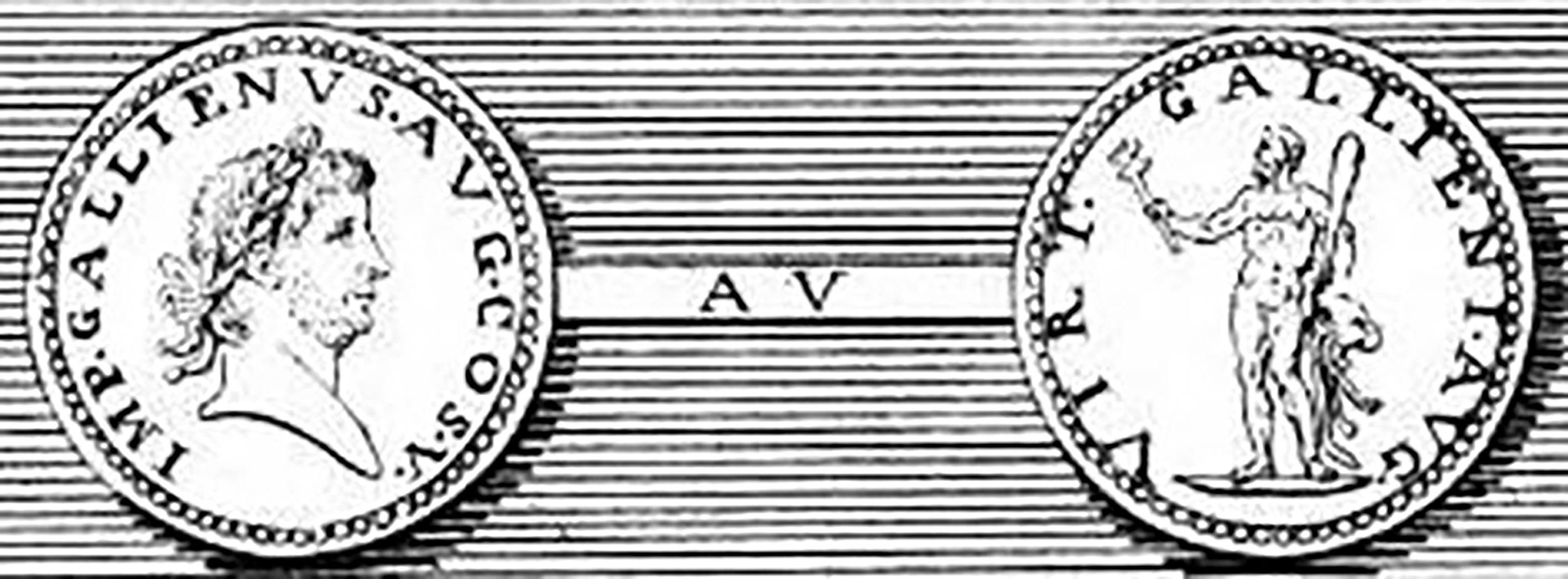

The description of the

Gallienus specimen allows to easily identify the medallion: on

the obverse the head of the emperor laureate to the right and

the legend IMP GALLIENVS AVG COS V; while on the reverse

Hercules standing to the left with the lion’s skin, a branch in

the right hand, a club in the left and legend VIRT GALLIENI AVG[6].

As

already mentioned, four medallions were sold to cardinal Albani,

but unfortunately we do not know the circumstances that

led to the acquisition of the other two specimens.

However, their description is provided

by Zeno himself in a letter of 13 March 1728, addressed to the

Somascan father Gianfrancesco Baldini (1677–1764) in Rome[7].

At this date Apostolo already intended to sell his medallions

with the aim of obtaining the maximum

profit. He was quite reluctant to sell portions of his

numismatic collection, although minimal, and

the statement »Una volta sola so d’aver venduto medaglie«,

leads to this conclusion, and suggests that it was a rather

exceptional fact. Perhaps he considered the

collection of gold medallions too expensive or too risky,

fearing of running into counterfeits[8],

and he came to the decision, certainly thoughtful, to sell the

four specimens in his possession with the aim, certainly not

secondary, to achieve a lucrative profit.

The following is the letter

Zeno wrote to Baldini: »A pié di questa (lettera)

troverà la descrizione dei quattro medaglioni d’oro ch’io

tengo: dei quali però non sarò mai per privarmi per meno di 160.

ungheri. Non se ne faccia maraviglia del prezzo, poiché

pel solo Valente ho potuto averne 70. e gli ho ricusati, non

volendone meno di cento«[9].

In addition to the already mentioned

specimens of Valens and Gallienus, Zeno reported the description

of the other two medallions:

I. IMP GALLIENVS AVG COS. V. Gallieni caput galeatam.

VIRT GALLIENI AVG.

Hercules nudus, dextrorsum stans, dextra oleae ramum, sinistra

clavam erectam, leoninis spoliis in laevum brachium rejectis.

Pesa quattro ungheri [»weighs four

ungheri«].

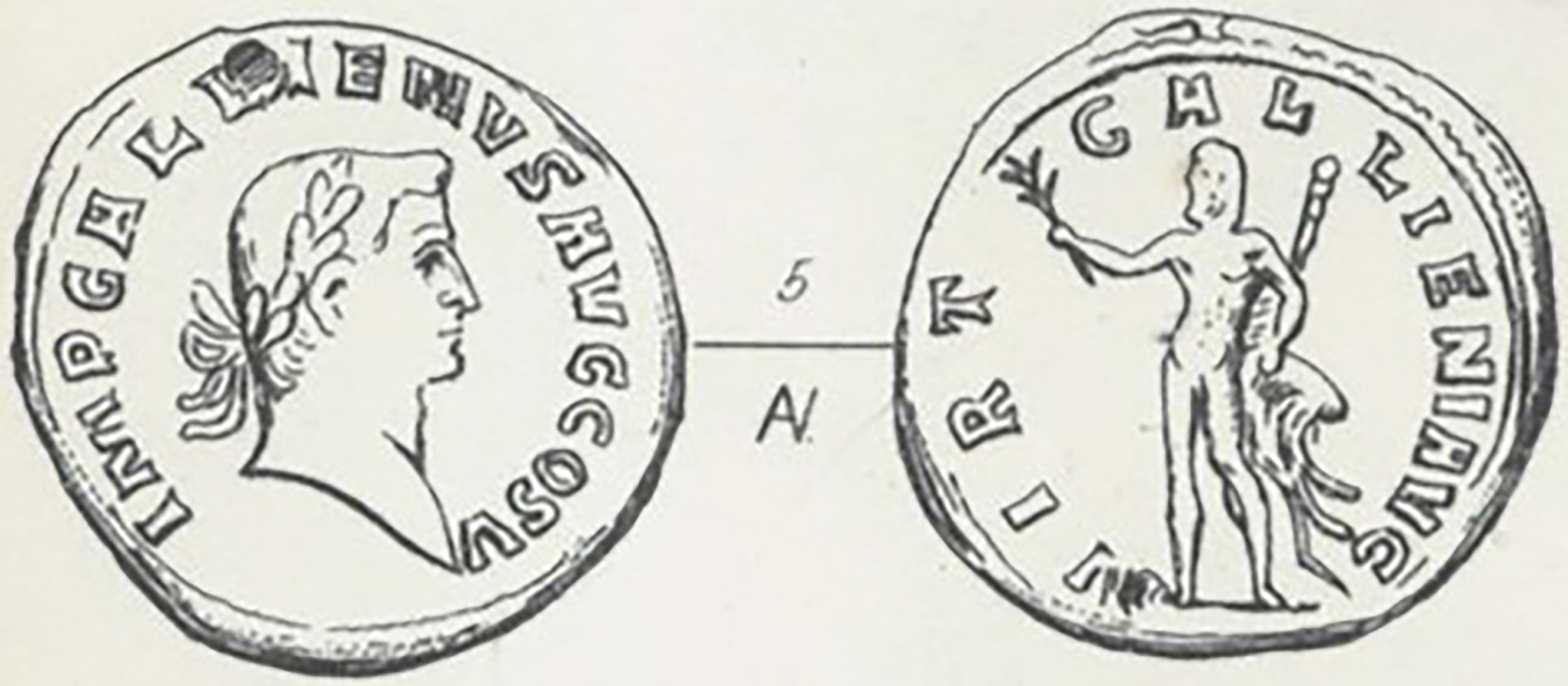

II.

FL VAL CONSTANTIVS NOB CAES. Caput Constantinii Chlori

radiatum.

PRINCIPI IVVENTVTIS.

Constantius laureatus, habituque militari ornatus, sinistrorsum

stans, d. spiculum transversum gestat, s. globum. In imo

PROM. Pesa quattro ungheri [»weighs

four ungheri«][10].

III.

D N VALENS MAX. AVGVSTVS. Caput Valentis cum diademate

ex lapillis & margaritis, cum paludamento ad pectus gemmata

fibula revincto, dextram expansam altollens, s. victoriam tenet,

quae s. ramum gerit, d. vero laureolam porrigit Imperatori.

D N VALENS VICTOR SEMPER

AVG. Imperator nimbo ornatus, cum paludamento ad pectus, a

fronte stans, super currum a sex equis tractum, dextra expansa &

elata, s. globum tenet. Hinc & inde volitant duae victoriae

lauream illi porrigentes. In ima parte plures, ut videntur,

monetarum acervi, & litterae R M. Pesa dieci ungheri e mezzo in

circa [»weighs about ten ungheri and

half«].

Sopra questo medaglione il P.

Paoli ha stampata un’erudita dissertazione

[regarding this medallion, P. Paoli wrote

an erudite dissertation][11].

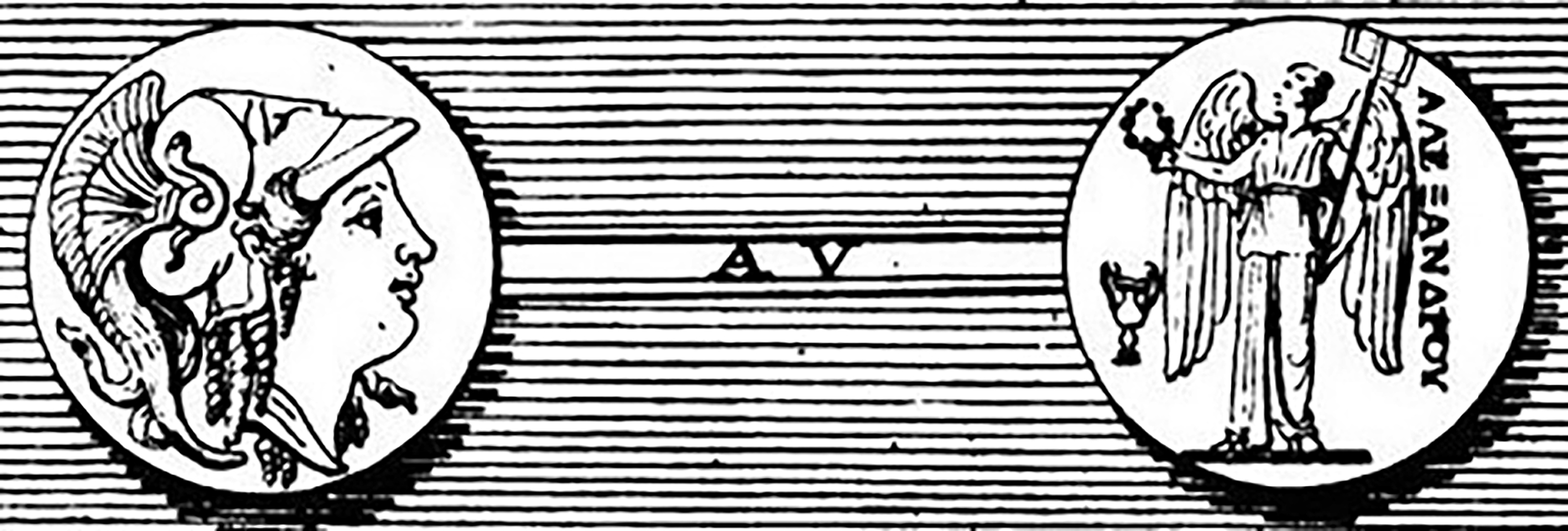

IV. ALEΞANΔΡΟΥ.

Victoria dextrorsum stans, d.

lauream, s. sceptrum: pro pedibus, vas utrinque ansatum.

Pesa cinque ungheri [»weighs

five ungheri«][12].

The

letter to Baldini provides a last important information:

»Tutti i suddetti medaglioni d’oro purissimo

sono d’indubitata antichità, e d’intera conservazione. In quello

di Gallieno v’è un buco sopra la testa; e questo è il solo

difetto che v’abbia«[13].

The exact date of the

sale of the medallions to Albani is unknown but in 1738 the

collection of the medallions of the Cardinal, including the four

specimens sold by Zeno, passed to the Vatican collection[14]

and the transaction, therefore, must have occurred before that

year.

Between 1739 and 1744 a

work was published, in two volumes, edited by Rodolfo Venuti

(1705–1763)[15]:

»Antiqua numismata maximi moduli Aurea, Argentea, Aerea,

ex Museo Alexandri S.R.E. Card. Albani in Vaticanam Bibliothecam

a Clemente XII Pont Opt Max translata (…)«, in

which he described many of the medallions of the

former Albani collection, and among them, the four specimens

which had belonged to Zeno. In the first volume,

published in 1739, the double stater of Alexander the Great

is indicated (see note 12, and fig. 1) with a weight

of 16.767 g[16],

lighter than the one reported by Zeno (»cinque ungheri«,

about 17.25 g, see note 3). The other three specimens were

included in the second volume, published in 1744; following the

chronological order it mentioned the medallion of Gallienus (fig.

3), with a weight of 13.91 g[17],

almost the same cited by Zeno (»quattro ungheri«,

about 13.8

g). It is however important to

highlight a detail: its reproduction does not present the hole

over the head (see above). It could be an oversight or, more

likely, the engraver’s intention to show the intact medallion[18].

The last two specimens, related to Costantius Chlorus (fig.

6)

and Valens (fig. 2), are respectively of a weight of

12.64 g (Zeno indicated »quattro ungheri«,

13.8 g)[19]

and 36.25 g, almost the same mentioned

by Zeno (»dieci ungheri e mezzo in circa«)[20].

The medallions were

displaced in 1798, when, under the terms of the treaty of

Tolentino, stipulated the previous year, the specimens from the

Albani collection, as well as many other precious coins, were

taken from the Vatican collection by the delegates

of the French Republic, and brought to Paris[21].

We can affirm with

reasonable certainty that two of the four medallions belonged to

Apostolo Zeno are now kept in the British Museum, both coming

from the Louis de Blacas d’Aulps collection, which was entirely

purchased by the Museum in 1867. The first medallion is

the Gallienus one (Museum

number 1867,0101.821, with a

weight of 13.980 g, fig. 5), declared to be owned, in the

information entry of the Museum, by the Duke of Blacas[22].

The aristocrat is mentioned as the owner of the specimen also in

the fourth volume of the first edition of Henry Cohen’s work, »Description

historique des monnaies frappées sous l’Empire Romain«,

published in 1860[23].

In 1868 Frederic W. Madden (1839–1904) writing for the

Numismatic Chronicle about the gold coins of the Blacas

Collection acquired the previous year by the British Museum,

reported exactly this

Gallienus medallion (fig. 4)[24].

The Duke’s name appears also in the Francesco Gnecchi’s work on

the Roman medallions, published in 1912, in which the author

reports the Gallienus medallion and, among the known pieces, a

specimen preserved in London with the following words: »già

Blacas anticamente Vaticano, m. 28, gr. 14.000«[25].

It is obviously the medallion kept in

the British Museum with the identification number mentioned

above, and it is more than plausible to

conclude that it is the same specimen belonged to cardinal

Albani, and before to Apostolo Zeno, even more so if we consider

the provenance of the Vatican collection.

Lastly, to corroborate the hypothesis there is also

another important clue represented by the hole placed over the

head of Gallienus, a detail also reported by Zeno in his letter

to Baldini (»un buco sopra la

testa«, see above).

Thanks to the

publication of Gnecchi we can trace also the location of the

Costantius Chlorus medallion. In the

concerning form the author wrote: »Londra (già Blacas

anticamente Vat. Alb.) m. 25, g. 12,975«[26].

Therefore, this specimen followed the same path of the previous

one to reach the collection of the British Museum, where it is

still kept (Museum

number 1867,0101.879, with a weight of

12.830 g, fig. 7)[27].

The research of the

specimens that belonged to the numismatic collection of Apostolo

Zeno is partly the subject of my doctoral thesis, and represents

a fascinating evolving path that it can never really says to be

concluded. Nevertheless, every coin found,

and returned, to its collector’s history helps to keep

alive the interest for a collector and

a collection that do not really deserve to be forgotten.

* This article mainly derives from

my doctoral thesis: »La collezione numismatica di

Apostolo Zeno«, a research project in

collaboration between the Universities of Venezia Ca’

Foscari, Udine and Trieste, and in cooperation agreement

with the Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster.

[1]

The

Diary was written by Marco Forcellini (1712–1793), the

personal secretary and friend of Apostolo Zeno, and it

contains some passages of the conversations the two

entertained since 1745. The manuscript is kept in the

Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana in Florence, Fondo

Ashburnham 1502, and its content were published in 2012

edited by Corrado Viola with the title of »Diario

Zeniano (Firenze, Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Ashb.

1502) Marco Forcellini«.

[2]

Apostolo Zeno (and his numerous interlocutors), in all

documentation examined, refers to ancient coins as

»medals«. This use originated

from the XIV century and in the XVIII

century it was fully accepted. See

Saccocci

2001, 58 and, for further details on

this issue, Missere Fontana 1995 and

Mc Crory

1999.

[3]

»Only once I had sold medals: they were four gold

medallions, which I gave to Albani for 170

zecchini,

and to me they cost 25 ongari« [=

Hungarian ducats]:

Viola 2012, 97. At the

time of Zeno, the ongaro (or

ungaro,

unghero) weighed approximately 3.45 g with a gold

content of 986/1000: cf. Martinori 1915, 354, under the

heading »Ongaro di Cremnitz o di Kremnitz«. This coin

had about the same weight of the

zecchino of

Venice, and in 1745 (the year of this statement), the

doge was Pietro Grimani (1741–1752) and his

zecchini

had a weight between 3,37 g and 3,50 g: cf. CNI

VIII, 451, n° 53–54; Montenegro 2012, 592, n° 2644;

finally, see a coin of Grimani auctioned by the Auction

House Bertolami Fine Art (E-Auction 97, 27–28 March

2021, Lot 1420).

[4]

»The past few days I

bought here another beautiful gold medallion, weighting

four ungheri, with the head of Gallienus on one

side, and on the other Hercules with the club and the

lion skin, and the legend VIRTVS GALLIENI AVGVSTI«:

Lettere Zeno 1785, vol. III, Lett. 601,

382; cf. »Fontes Inediti Numismaticae Antiquae«

(from now on, »FINA«), ref. 6744:

https://fina.oeaw.ac.at/wiki/index.php/Apostolo_Zeno_-_Andrea_Cornaro_-_1723-9-14

[transl. R. Tomassoni].

[5]

Lettere Zeno 1785, vol. III, Lett. 535,

226–227; cf. FINA, ref. 6793:

https://fina.oeaw.ac.at/wiki/index.php/Apostolo_Zeno_-_Pier_Caterino_Zeno_-_1721-1-4;

Viola 2012, 97, suggests that

the Count Lippe could be Rudolf Ferdinand Count of

Lippe-Biesterfeld (1678-1736); Tomassoni

2021, 113–115. The medallion will be described below in

further detail.

[7]

The friendship and the epistolary exchange

between Zeno and Baldini intensified from 1723–1724,

when Apostolo bought the collection of

Roman

imperial silver coins of the Somascan Father.

Baldini’s competence in the

numismatic field is well known and

it is enough to mention

his updated edition of the work of Jean Foy Vaillant

(1632–1706): »Numismata imperatorum Romanorum

praestantiora a Iulio Caesare ad Postumum«, in

three volumes, published in Rome in 1743. For a complete

analysis on these issues I refer to my doctoral thesis,

Tomassoni 2021, in particular to chs. 2

(pp. 27–36), and 6.

[8]

The counterfeiting was an

issue much felt by Zeno and in general by collectors of

his time, see Tomassoni 2021,

ch. 5. The question of false coins and their authors was

already known and discussed in the 16th century, see

Missere Fontana 2013.

[9]

»At the foot of this

(letter) you will find the description of the four

gold medallions that I have: of which, however, I will

never be deprived for less than 160. ungheri. Do

not be surprised by the price, since only for Valens I

could have 70. and I declined, not wanting less than one

hundred«: Lettere Zeno

1785, vol. IV, Lett. 736, 238; cf. FINA,

ref. 6654:

https://fina.oeaw.ac.at/wiki/index.php/Apostolo_Zeno_-_Gian_Francesco_Baldini_-_1728-3-13

[transl. R. Tomassoni].

[10]

Cohen 1888, vol.

VII, 79, n° 227.

[11]

Cf.

RIC IX, 122, n° 25.

The dissertation of Father Sebastiano

Paoli (or Pauli, 1684–1751) was published in 1722 under

the title »De Nummo Aureo Valentis Imp«.

For more information on this kind of medallion, see

Vondrovec 2010.

[12]

Lettere Zeno 1785, vol. IV, Lett. 736,

239–240. The last medallion

mentioned is clearly a double stater of Alexander the

Great, cf.

Price 1991, vol. I, 107, n° 167.

[13]

»All the mentioned

medallions are of pure gold and undoubtedly antique, and

well-preserved. In Gallienus’ one

there is a hole over the head; and

this is the only defect« [transl. R. Tomassoni].

[14]

Le Grelle 1965, p.

XVIII.

[15]

Indeed, Venuti reached a remarkable reputation thanks to

the editions of the numismatic catalogues of Albani’s,

Mattei’s and Odescalchi’s collections. In 1734 he also

became auditor in Rome of cardinal Albani and the

curator of his antiquarian collection. In 1744 Pope

Benedict XIV (1740–1758) appointed Venuti as apostolic

antiquary and apostolic commissioner over all

›archaeological excavations‹: see Cristofani 1983, 49.

[16]

Venuti 1739,

vol. I, 1 and pl. 1. Following

the text: »Ex Auro. Pond. Den. XIV. Gr. IX.«:

the weight is therefore 14 deniers and 9 grains. If we

consider that 1 ounce = 24 deniers, 1 denier = 24

grains, and 1 grain = 0,0486 g (the weight equivalence

in the city of Rome, see Martinori

1915, 191), we will have the following equation:

[(14 x 24) + 9] = 345 grains x 0,0486 g = 16,767 g.

[17]

Venuti 1739, vol. II, 47

and pl. 83. The weight is 11

deniers and 22 grains: it means 13.91 g (see above).

[18] The

engravings of the medallions were made by the painter

Gaetano Piccini: see Le Grelle 1965, p. XVIII, note 10.

[19]

Venuti 1739, vol.

II, 103 and pl. 111. The weight is 10 deniers and 20

grains: it means 13.8 g (see note 16).

[20]

Venuti 1739, vol. II,

109 and pl. 114. The weight is 1 ounce, 7 deniers and 2

grains: it means 36.25 g (see note 16).

[21]

Gnecchi 1905,

16 and following. See also Gnecchi

1912, vol. I, 36 (about Valens’ medallion).

The treaty of Tolentino was signed on 19 February 1797

between the French of Napoleon Bonaparte, who had

occupied the papal territories of central Italy, and the

diplomates of Pope Pius VI (1775–1799). In particular,

the articles 10 and 12 of the treaty obliged the Pope to

pay to the French army a compensation of 30 million of

lire tornesi (tornesel or tornese), in cash,

diamonds and other precious objects.

To deepen this topic, see Filippone

1959.

[22]

In this entry there were no

references to Apostolo Zeno or cardinal Albani; these

were recently added following the hypothesis of this

article, formulated previously in my doctoral thesis.

[23]

Cohen 1860, 353, n° 22.

[24]

Madden 1868, 13 and pl. IV, n° 5.

[25]

»(F)ormerly Blacas, anciently

Vatican, mm 28, 14.000 g«:

Gnecchi 1912, vol. I, 7–8, n° 16.

[26]

»London (formerly Blacas

Vat. Alb.) mm. 25, 12.975 g«:

Gnecchi 1912, 13, n° 3.

[27]

Also this specimen is

described in the first edition of the work of Henry

Cohen (see above), in the fifth volume, as belonging to

the collection of the Duke of Blacas: Cohen

1861, 553, n° 6; the medallion is reported as

well in the already mentioned publication of Madden

1868, 28, n° 300 and pl. V, n° 10.