Some New Insights and a Note Regarding Alexander Jannaeus Anchor/Star (TJC Group L) Coins

Abstract:

The article examines one specific type of

coin that was minted by Alexander Jannaeus and probably by his

successors, during the first century BCE. New variants and

unpublished specimens are discussed along with a proposal that

this coin type may be divided into four subtypes. The article

also considers the preparation of the dies used to mint the

smallest of this type of coin. Finally, the article proposes the

denomination that these coins had in the ancient Judean

marketplace.

Key Words:

Alexander Jannaeus http://d-nb.info/gnd/1048422461,

Judea

https://pleiades.stoa.org/places/687934, 1st century BCE –

1st century CE, Khirbet el-Maqatir http://d-nb.info/gnd/1151919179

Zusammenfassung:

Dieser Artikel untersucht einen spezifischen Münztyp, der von

Alexander Jannaeus und wahrscheinlich von seinen Nachfolgern im

1. Jh. v. Chr. geprägt wurde. Neue Varianten und unpublizierte

Exemplare werden diskutiert, einhergehend mit dem Vorschlag,

diesen Münztyp in vier Untertypen aufzu gliedern. Daneben wird

die Herstellung der Stempel berücksichtigt, mit denen die

kleinsten Exemplare dieses Typs geprägt wurden. Schließlich

machen die Autoren einen Vorschlag, welches Nominal diese Münzen

im judäischen Zahlungsverkehr einnahmen.

Schlagwörter:

Alexander Jannaeus, Judäa, 1. Jh. v. Chr. – 1. Jh. n. Chr.,

Khirbet el-Maqatir

The most common Jewish

coin in the archaeological record in Israel is a small bronze

coin minted by Alexander Jannaeus and likely by his successors

as well. Ya‘akov Meshorer in his »A Treasury of Jewish

Coins« (below cited with the common abbreviation TJC)

labels this type as group L with seventeen variants[1],

although there are apparently many dozens more. The obverse of

this type has an anchor surrounded by a circle; around the

circle is a Greek legend, on many of the coins imitative. The

reverse has an eight or six-ray star surrounded by a border of

dots; around the border is an Aramaic legend, on many of the

coins imitative. TJC L is also the only group of

Alexander Jannaeus coins that has a date (»year 25« = 79/8 BCE).

Since the publication of

TJC, more than twenty years ago, an abundance of

new data is available that facilitates an affirmation and a fine

tuning of Meshorer’s conclusions. In this essay we seek to offer

a few insights on the TJC group L coins: 1) There

are two new variants of a star, now with five and seven rays. 2)

We propose that scholars discuss the TJC group L

coins in terms of four subgroups instead of identifying an ever

growing list of variants. 3) We present an unpublished and

interesting variant which proves that some dies were

intentionally made with a partial star image. 4) We propose that

two of our subgroups were intentionally struck on small and

irregular flans by Jannaeus successors to serve as half-prutah

coins.

Insight No. 1: Two new variants – five

and seven ray stars

Two new variants in the depiction of the star for the TJC group L coins were recently discovered. The first variant depicts a star with five rays; one specimen of this type was discovered at Khirbet el-Maqatir[2] (0.61g, 5x7mm; fig. 1)[3] and a second is from a private collection (0.57g, 10x12.5mm; fig. 2)[4].

Fig. 1: From Kh. el-Maqatir, No. K041199

The second new variant

depicts a star with seven rays. The excavations at Khirbet

el-Maqatir produced two such coins (figs. 3 and 4). These

two coins were initially identified and discussed in the final

excavation report for Khirbet el-Maqatir[5].

Even though two different dies produced the coins with seven

rays, we are of the opinion that this is nothing more than an

anomaly resulting from poor craftsmanship in the making of the

dies. If a seven-ray star, or even a five-ray star, was

intentional we would expect that many more coins with five or

seven rays would have been found throughout Israel.

Fig. 4: From Kh. el-Maqatir, No. K045186

Insight No. 2: The TJC group L coins may

be divided into at least four subgroups

As stated above,

Meshorer’s standard reference for ancient Jewish coins, »A

Treasury of Jewish Coins«, classifies coins into major

types along with many variants of those types. For the group L

coins Meshorer lists seventeen different variants[6].

They show such things as: variations in spelling, missing

letters, variations in the number of rays of the star, parts of

link pieces still attached to the flan, rays of the star

represented by dots, legends missing on the flan because the

smallness of the flan, and several other factors. While there is

value in identifying variants, with each new coin that is

discovered there is the likelihood of the list becoming longer.

While this is not a concern in and of itself, when it comes to

discussing the coins, numismatists have tended to group variants

into groups. For example, over the past twenty years, for

purposes of discussing the TJC group L coins,

numismatists have tended to group together L1–6 and L7–17[7].

The rationale for this division may lie in TJC’s

description of the variants. Beginning at L7 Meshorer uses the

adjective »crude« and this then defines the remaining variants.

Having examined hundreds of TJC group L coins we

think that there are at least four main subgroups, rather than

two.

Subgroup L-I (fig. 5):

Designates coins whose flan is of sufficient size to accommodate

the legend on the outer edge of each side of the coin. The star

is depicted as having eight rays. These coins are the largest

and heaviest in this series (mean weight 1.27g and ranging

12–16mm in diameter)[8].

Most of the TJC group L1–3 coins would fall into

this subgroup. Likely a development of the Alexander Jannaeus’s

TJC group K coins, we consider this subgroup the

principle issue of group L.

Subgroup L-II (fig. 6): Designates coins whose flan is slightly smaller and results in the legend on one or both sides of the coin to be significantly missing. The star is depicted as having eight rays and they are slightly smaller than L-I subgroup (mean weight 0.84g and ranging 8.5–15mm in diameter). Often the star is struck with more than 50% of it missing. Most of the TJC group L4–7 coins would fall into this subgroup. We consider this subgroup a contemporaneous less careful issue of group L-I, serving as the same denomination.

Fig. 6: From Kh. el-Maqatir, No. K044747

Subgroup L-III (fig. 7): Designates coins with smaller flans and the star is depicted as having six rays with the Aramaic legend, which includes Alexander Jannaeus’s name and the date »year 25«, removed. The size of the flan continues to shrink with the mean weight ~0.52g and the diameter ranging 7–14.5mm. Most of the TJC group L8–13 coins fall into this subgroup.

Fig. 7: From Kh. el-Maqatir, No. K041327

Subgroup L-IV (fig.

8): Designates coins that have the anchor hardly seen on one

side and just one or two rays of a star and dots that are linear

rather than forming a circle (one can also see an example in

TJC L14). This subgroup is not just an even poorer

striking from an eight or six-ray die, as if the image is

accounted for by the die being off center to the flan. The eight

or six-ray die has the dots that make up the border circle at

the outer end of the rays. This particular die places dots

parallel to the ray, even down at the base of the ray. If it was

a regular die used on a very small flan we probably would not

see any dots on the star side. Additionally, we project that if

a die used to strike the star was a complete image (like the L-I

coins), that die would be at least 20 mm in diameter. This is

too large given the flan size. Therefore, the die was

intentionally made with just one ray and did not include a

complete star with a doted circle and legend around it (see

further discussion below, Insight 4). These flans are the

smallest in the L group, with a mean weight of just ~0.29g and a

diameter that ranges 5.5–12mm.

Fig. 8: From Kh. el-Maqatir, No. K045115

Insight No. 3: Some dies were

intentionally made with a partial star image

The following unpublished coin is from a private collection (0.5g, 9x10mm; fig. 9)[9]. The side of the star has two rays only, with two dots in between them and two square blundered imitations of Aramaic letters, which look like the Greek letter Π (pi). The other side has 3/4 of the anchor within a plain circle and some Greek letters around it, of which only the letter Λ (either lambda or alpha) is clearly visible.

Fig. 9: Ziv Zur collection (photo by Ziv Zur)

To assist in analyzing this unique coin, we placed the coin next to another TJC group L coin (fig. 10). Both coins are similar in size with the bottom coin being just 1mm larger (9.5 x 11 mm). The proportion of the anchor that is visible and space for the corresponding legend beyond the circle of the anchor is consistent between both coins. The coin from the private collection is thick enough to have a beveled edge visible on the anchor side; unlike the bottom coin which is too thin for a bevel. The imitation Aramaic lettering underneath the rays of the star are in a straight line; unlike the legend that curves around the dots that circle the star on other TJC group L coins. In addition, a close examination of the coin reveals what seems as a plain circle (in low relief) above the two rays, not part of the engraving of the die, but perhaps the physical edge of the die (see fig. 11).

Fig. 10: Ziv Zur coin on top; TJC group L coin on bottom from Kh. el-Maqatir, No. K041327

Fig. 11: The possible edge of the die above the rays

Generally, it seems that

the dies which were used for the crude types of TJC

L (our groups III–IV) are usually one and a half to two times

larger than the image actually struck on a coin. The size of

this coin (9x10mm) and the size of the designs suggests that in

this case the die used for the anchor was ~16mm and the die used

for the star was ~10mm[10].

The die used for the anchor is clearly too large for the flan.

But for the star, what we see on the coin is evidence that at

least in this case the die was intentionally made to not include

a complete design of a star with six or eight rays and a

complete legend around it, but only part of the whole design was

included in the die. Likewise, one should note that no such

possible frame can be seen around the design on the anchor side,

supporting the position that a larger die was used to strike

that side. This partial star die, which includes part of the

star (two rays), part of the surrounding dotted circle (two

dots) and part of the surrounding legend (two letters), was good

enough to represent the whole design in order that it could be

identified by the person who would use it.

In reviewing the coins from Khirbet el-Maqatir we discovered an interesting parallel to this coin. The five-ray star coin from Khirbet el-Maqatir (fig. 1) is similar in weight to the coin from the private collection (0.61g compared to 0.5g), but it is one-third the size (5x7mm compared to 9mm). As already mentioned the star is depicted with five rays, unusual for these Alexander Jannaeus coins since they are typically six or eight rays. But the most curious feature is the spacing of the rays, the two dots between the rays, and the surviving letters underneath the rays (fig. 12). A die-link is not possible for these two coins due to the difference in size. Likewise, there is nothing on the Khirbet el-Maqatir coin that could account for the possible mark from the edge of the die above the rays as appears on the coin from the private collection (fig. 11). Nevertheless, we suggest that the inspiration for the die that was used for the two-ray coin comes from imitating part of a five-ray star with dots and letters.

Fig. 12: From Kh. el-Maqatir, No. K041199 with rays, dots, and lettering similar to the coin in fig. 9

Using our proposed

sub-types, Insight 2 (above), we would place this coin from the

private collection alongside the L-IV subgroup. This grouping is

justified for two reasons. First, the commonality of a small

flan. Second, the image of a star struck by a die that was

intentionally made with a partial star image.

If we are correct in our

basic understanding of this coin, then there is a significant

implication that leads to our final insight – that groups L-III

and L-IV were intentionally struck on small and irregular flans

to serve as half-prutah coins, likely by Jannaeus’s

successors.

Insight No. 4: Groups L-III and L-IV were

intentionally struck on small and irregular flans to serve as

half-prutah coins, possibly by Jannaeus's successors

Numismatists have long

acknowledged the difficulty in naming and assigning

denominational value to Judean bronze coins. Citing Arie Kindler[11],

David Hendin affirms that the Judean bronze coins are most

properly called prutot (sg. prutah) and half-prutot

(also called a lepton in Greek)[12].

In his study of the metrology of these small bronze coins Hendin

confirms the view of Meshorer that the denominations are not

distinguished by weight. Rather, one distinguishes the

denominations by the design of the coin[13].

Hendin makes the following conclusions about the denominations

of some of the Judean small bronze coins:

1)

The irregular TJC group L coins are degraded

prutot and not half-prutah coins. Hendin says that

Alexander Jannaeus did produce a half-prutah coin as

evidenced in the coin’s different design but they are very

scarce[14].

Hendin probably meant TJC group O coins, although

he did not state this.

2)

Mattathias Antigonus did not mint half-prutot[15]

3)

Herod I did mint half-prutot but they have proved to be

quite rare in the archaeological record[16]

4)

Herod Archelaus minted a half-prutot[17]

5)

Hendin does not identify anyone else who minted Judean bronze

coins of the half-prutah denomination.

Accepting the conclusion

that the design and diameter is the key to distinguishing the

denomination (in most cases regarding bronze coins), our

proposal is that the L-II subgroup was minted contemporaneous to

L-I subgroup or in subsequent years but prior to Alexander

Jannaeus’s death. The smaller flan that was used for the L-II

subgroup may have been necessitated by the population’s need for

prutot given the large geographical expansion of

Jannaeus’s kingdom. The smaller flans allowed for more coins to

be minted from the same amount of metal.

We also propose that the

L-III and L-IV subgroups were minted after Alexander Jannaeus’s

reign and that they, along with the L-II already in circulation,

were used as half-prutah coins by the time of the first

century CE[18].

This proposal takes into account three considerations: the

change in the dimensions (weight and diameter) and shape of the

flans (from round flans to more oval or elongated); the design

of the TJC group L coins, from a star with eight

rays to one with six to one with two or fewer rays; and the

historical reality of a lack of half-prutot in the first

century CE, along with the high frequency of L-II, L-III, and

L-IV coins recovered in first century CE contexts (see Table 1

for a summary)[19].

Table 1: Suggested

denominational usage of TJC

group L coins

|

Group L |

During

Alexander Jannaeus’s Lifetime |

Mid 1st

century BCE |

By late 1st

century BCE |

|

L-I |

Prutah |

Prutah |

Half-prutah

|

|

L-II |

Prutah |

Prutah |

Half-prutah

|

|

L-III |

|

Prutah

or half-prutah (?) |

Half-prutah

|

|

L-IV |

|

Half-prutah

|

Half-prutah

|

There are two

distinguishing characteristics between the L-II and L-III types,

regarding the dies presenting the star. The first is the change

from an eight-ray star to a six-ray star. The second is the

removal of the Aramaic legend which includes Alexander

Jannaeus’s name and the date »year 25«. We think it is

reasonable that these two changes are an acknowledgement on the

part of the engravers that these coins are not ›real‹ Alexander

Jannaeus coins. Thus these coins were minted after the death of

Alexander Jannaeus. We think it is most reasonable to assert

that the striking of the L-III coins occurred in the mid-first

century BCE. Whether the L-III types were intended to be

prutot or half-prutot remains undetermined. Hendin

believes that the intent of these coins was to be prutot,

especially when initially struck in the mid-first century BCE[20].

We have no firm objections to this conclusion. However, we do

not wish to rule out the possibility that the L-III coins were

minted after Alexander Jannaeus reign to serve as half-prutot

while the L-I and L-II continued to be used by the

population as prutot (along with all the other types of

Alexander Jannaeus’s coins; see more below).

As for the L-IV coins,

these coins are the most difficult to understand. Part of the

difficulty in understanding this proposed subgroup is that these

coins are usually not collected in excavations that do not use

metal detection; consequently, they do not appear in reports. As

we commented above, the dies used to make these coins appear to

be purposeful. Perhaps the creation of a one-ray or two-ray star

die was nothing more than an aesthetic gesture since the flans

had become so small. Such a die ensured that at least one or two

rays would be visible instead of the potential for no rays to be

visible with the use of a larger die on such a small flan. When

the L-IV coins were struck and their denominational value are a

great enigma. Whatever one concludes about the date of striking

and the denominational value of the L-III coins likely applies

to the L-IV coins[21].

In any case it is hard to believe that the denominational value

of the L-IV coins, which are the tiniest and the most crude of

this type, was intended to be the same as L-I–III coins, thus

they were most probably struck in order to serve as half-prutot.

Regardless of the

original denominational value of the L-III and L-IV coins, we

believe that by the late first century BCE and first century CE

these coins were used as half-prutot[22].

There are two main reasons for our suggestion. First, while the

ruling authorities (i.e., the Herodians and the Roman governors)

are producing prutot in the late first century BCE and

first century CE, there was a lack of production of half-prutot

in this period and especially during the first century CE. As

mentioned above, no one has suggested that half-prutot

were minted after Archelaus. Second, the archaeological data

shows the frequency of the TJC group L coins found

in first century CE contexts[23].

In the first century CE people are clearly using the TJC

group L coins, and thus it seems that there was a need for these

coins, probably as half-prutot[24].

If the ruling authorities are not producing enough of this small

change then the people are meeting their need by continuing to

use the Alexander Jannaeus TJC group L coins more

than a century after they were struck or by the (tolerated?,

unauthorized?) minting of some of these coins during the first

century CE.

A Note regarding the production technique

of TJC L coins

In 1922 Hill discussed

the ancient methods of coining. One of his insights was that

a very common fault, especially in small

coins, was caused by the dies being badly registered, so that

only part of the type of one side was struck on the blank, the

greater part of the blank being left empty. This faulty

adjustment, in the case of blanks cast en chapelet and

not separated before striking, but placed on an anvil in which

several obverse dies were set, would produce coins with

impression of parts of two different dies on the same side. The

blank was evidently placed so as to lie partly on two obverse

dies, and the reverse die was brought down on it; thus a

complete reverse impression was associated with two partial

obverses[25].

One of his examples was

a coin of Alexander Jannaeus published by him in his BMC

Palestine[26].

In 2014 Nikolaus Schindel published a note on the production of

Hasmonean coins, showing more examples of this technique. He

also noted »significantly, basically all scholars who have

discussed multiple dies have assumed that they were cut into the

metal block at the same time and used simultaneously (…) my idea

is that the purpose of cutting several die impressions into the

same piece of metal was simply to make the most economical use

of the block of metal without remelting and totally reworking

it«[27].

We accept the suggestion

that the technique of striking the flans on an anvil into which

several dies were cut (rather than small circular dies set into

the anvil) was used for Hasmonean coins, including coins during

Alexander Jannaeus’s reign. We suggest that this technique could

have been altered in order to advance the striking process of

TJC L coins, especially L-II–IV. While hundreds of

flans could have been prepared simultaneously in connected-flan

molds[28],

striking them, one-by-one was likely not very efficient. Any

method that would make it easier to produce large numbers of

coins quickly would have been welcomed by the mint workers. Thus

we suggest, yet without proof, that flans could have been struck

simultaneously, while they are still attached to the strip, by

using an anvil into which images of several lower dies were cut

and a hammer into which images of several upper dies were cut.

Another option is that a rectangular metal block, into which

images of several upper dies were cut, was placed on the strip

and then hit by a large hammer held by the mint worker; thus, in

one hit he could actually strike several coins. This technique

could be especially useful for coins of a small diameter, such

as types L-II–IV.

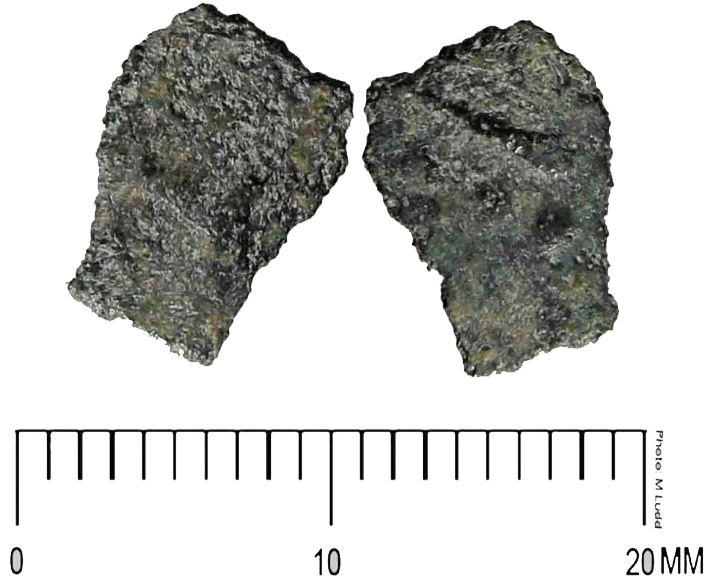

Within this discussion we also note the existence of many L-III–IV coins that were struck on what appears to be pieces of metal initially refused from the casting process. Excavation reports seem, in most cases, to avoid publishing these extremely defective coins. The excavation team at Khirbet el-Maqatir, with the use of a metal detector, recovered dozens of these specimens, struck on flans with almost no resemblance of a legitimate coin. Upon inspection it seems that all of them have one side which was attached to a flan strip and all of them are beveled; thus, we can assume that they are defective flans (and not just pieces of scrap bronze), perhaps the last ones in each strip of flans. A wide variety of such specimens were chosen for publication in the Khirbet el-Maqatir excavation final report, with a few shown here (Fig. 13)[29].

Fig. 13: Representative coins from Khirbet el-Maqatir struck on defective flans

Why these defective

flans were struck instead of being gathered, remelted, and cast

into ›normal‹ flans, is unknown. Maybe it was out of

indifference since the coins were mass produced, resulting in

little concern for quality control. The mint was given a certain

amount/weight of bronze to make coins and the money bag was

returned with the same weight of coins. The production of such

crude coins, struck on defective flans, and their use in

circulation might be another possible evidence that types

L-III–IV were struck after Jannaeus, as he would probably not

agree to the use of such coins, never seen before.

[1]

TJC, p. 210.

[2] The

Associates for Biblical Research excavated Khirbet

el-Maqatir from 1995–2000 and 2009–2016. Khirbet

el-Maqatir is located in the central hill country of

Judea 16 km north of Jerusalem (NIG: 213403 E / 605355

N). For the publication of the coins see Farhi

forthcoming.

[3]

Unless otherwise noted, all of the coin photos are by

Michael C. Luddeni. We wish to thank C. Corbin Kuhn for

formatting all of our figures.

[4] We

wish to thank David Hendin for permission to include

this coin in our study.

[5]

Larsen forthcoming.

[6]

TJC, p. 210, L1–L17.

[7] See

for example, Shachar 2004, p. 7; Ariel 2014, pp.

245–249, 251–254; Ariel 2016, p. 80; also Krupp (2011,

pp. 41–42)

finds it convenient to divide the small anchor/star

coins into two subgroups (his Types P and PB).

[8] The

metrology for all of the subgroups in the following

discussion was determined by using coins from Khirbet

el-Maqatir (cf. note 1). L-I:

18 coins; L-II:

149 coins; L-III:

491 coins; L-IV:

78 coins.

[9] We

wish to thank Ziv Zur, Israel, for permission to include

this coin in our study.

[10]

Reference Fig.10. For the coin in the private

collection, if the plain circle around the rays is

projected to a complete circle that surrounds the rays

and letters, then the image would be ~10mm in diameter.

For the TJC L coin, the rays are 4–5mm in

length; thus the radius of the star itself should be

10mm, with another 4–5mm for the circle and legends, the

star die would be ~15mm in diameter. Both coins have a

similar sized anchor. The size of a complete anchor is

~8mm. If another 8mm is added for a complete circle and

legend, then the anchor side would be ~16mm in diameter.

[11] Kindler 1967, p.

186.

[12] Hendin 2009, p.

107.

[13]

TJC, p. 71; Hendin 2009, p. 108.

[14] Hendin 2009, p.

113.

[15] Hendin 2009, p.

114.

[16] Hendin 2009, p.

117; GBC, p. 240–241, nos. 1185–1187.

[17]

Hendin 2009, p. 117; GBC, p. 245, no. 1197.

Contra Meshorer (TJC, p. 80 and 225, no.

72).

[18] In

the expanded discussion below, our proposal is not

suggesting that merchants and buyers in the ancient

markets were trying to count rays on these tiny, crudely

struck coins to distinguish their denominational value.

However, it would have been simple, as it is today, to

distinguish between L-I (and possibly L-II) in contrast

to L-III–IV, just by looking at the size and shape of

the flans.

[19]

Meshorer’s TJC group L1–3 coins are much

more scarce in excavations compared to other Alexander

Jannaeus coins. For example, at Khirbet el-Maqatir 18

coins of type L1–3 were found compared to 74 group K

coins and 720 L4–16 coins. A reasonable explanation for

this is that L1–3 coins were struck in a shorter period

(80/79–76 BCE at the maximum), while the other types had

much more time to appear.

[20]

Hendin 2009, p. 113.

[21]

Ideally, the question of when these coins were minted

could be answered if we could find and excavate a site

which was built and occupied during the reign of

Alexander Jannaeus and ceased being occupied prior to

Herod I. If such a site lacked L-III and L-IV coins,

then one could begin to build an argument for the

minting of these coins in the late first century BCE or

during the first half of the first century CE.

[22] See

also Krupp 2011, p. 42.

[23]

Rappaport 1984, p. 39; Syon 2014, p. 115; Syon 2015, pp.

45–47; Farhi 2016, p. 73; Larsen forthcoming.

[24] If

not after the Roman conquest of 64 BCE, certainly

after 6 CE, when, following the deposition of Herod

Archelaus Judea came under direct Roman rule, the

continued use of Alexander Jannaeus coins may have also

provided a not-so-subtle declaration against Roman rule

(for a more developed argument see Larsen forthcoming).

[25] Hill

1922, pp. 36–37.

[26]

BMC Palestine, pl. XXII:4.

[27]

Schindel 2014, p. 47. Woytek (2006, pl. 11.22) published

an image of a metal block (47x25mm) with two die

impressions cut into the metal (each impression is 17

and 15mm respectively).

[28] See,

for example Ariel 2012, p. 55 (Table 2), who list

several connected-flan molds, some with the ability to

make hundreds of flans at one time.

[29] The

coins in figure 13 will appear, with these numbers, in

Farhi forthcoming.