"Universities have caught up in many ways"

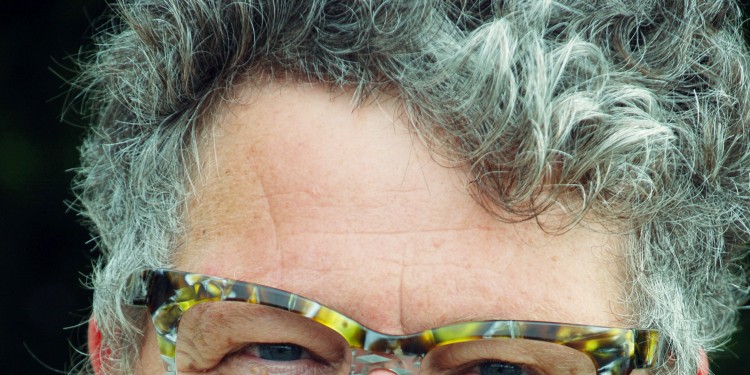

What status does work-family balance have at German universities? From 2011 to 2014 the Centre of Excellence/Women and Science (CEWS) in Cologne undertook a project on this issue entitled "Effective! – For a more family-friendly approach at German universities" Jutta Dalhoff has been head of CEWS since 2006. In this interview with Julia Schwekendiek she explains what characterizes a family-friendly university.

There is a growing public discussion on balancing family and career. How seriously is the topic taken at German universities?

Work-family balance is an important topic at universities because in higher education policy it is closely linked with the under-representation of women in science. It often used to be said that if we became more family-friendly the problem would be solved. Developments have shown, however, that simply being able to find childcare facilities does not lead to a greater presence of women in science. That there is a widespread focus on the issue is shown, for example, by organizations such as the "Family and Career" audit, which many universities take part in. A lot of people are also joining the "Family at University" best-practice club to exchange views at the work level.

Do you have the impression that universities have become more family-friendly in the past few years?

The issue has assumed a key role in the efforts made by universities to be a good employer and attract good staff. Universities have caught up in many ways that were already widespread in other areas of life. Compared with other countries, however, it must be said that the gender roles in Germany are still very traditional – in spite of a progressive family policy that can be seen, for example, in the issue of parental leave. In Europe, Iceland is right at the top, followed closely by Finland. In these countries there are many ways of bringing up children, with state support, in a very flexible way over a lengthy period of time. Both countries combine statutory regulations and good childcare facilities, which are available all over the country and are affordable.

The "Effective!" study carried out by CEWS showed that three-quarters of scientific staff have no children, even though many of them would like to start a family. Is this not much more an indication that the scientific world is not family-friendly?

Employment at universities is marked by a very rigid policy of fixed-term contracts. The decision to have children is put off till a later date – for very understandable reasons, because people often have to get by on limited contracts, moving from one project to the next, till the age of 40. Also, junior researchers are expected to be very mobile and to be available for long periods. This leads to many men and women who are in this situation wondering whether children have any place in their lives.

Are there any positive examples of family-friendly working conditions at German universities?

The idea of work-family balance is still linked strongly with women, even though that doesn’t correspond to everyday life in many partnerships and marriages today. What are the consequences of this for public discussions?

Although the prevailing conditions make it possible for fathers to take on greater responsibility for bringing up their children, this still happens only to a very limited extent in Germany. Dividing up parental leave equally between the father and the mother, for example, is an exception. Several studies have shown that in Germany a very traditional understanding of men’s and women’s roles is still widespread, and that not a lot has changed in people’s thinking. Of course, it’s not up to any one university to make changes here – it’s a task for the whole of society.

What, for you, would an ideal family-friendly university look like?

I would extend the notion to cover much more than it has so far. Traditionally, the instruments which universities use to create a more family-friendly environment are aimed at 30 to 40-year-olds – for example, flexible working hours and childcare facilities. However, these instruments have more the effect of supporting the existing system, putting women at a disadvantage for a lengthy period of time. Our working hours policies should take a different route to create a real work-life balance. Possibilities need to be created for both women and men which provide for more flexibility over their entire working lives. Last year, the German Women Lawyers Association (Deutscher Juristinnenbund) published a draft version of a law on flexible working times which would give employees the option of "saving up" working time during their working lives. By agreement with their employer they can have individual access to this account when they need time to look after their children, do voluntary work, take time off for health reasons, attend training courses or provide nursing care for family members. It won’t be possible to implement this quickly, but it’s the right proposal for meaningful staff development geared to different phases of life.

What steps need to be taken in the future in your view?

Using instruments aimed primarily at women won’t change the current situation much. Nor is it enough to provide certain offers for men such as paternal leave. A comparison with other countries shows that there need to be binding stipulations on how the various possibilities are to be used by both women and men – otherwise, traditional thinking will again lead back to an unequal distribution of support services. The only way to change that would be through relatively strict stipulations which would, of course, be controversial in our society.

Author: Julia Schwekendiek

Source: "wissen|leben" No. 6, 12 October 2016

Further information

- Entwurf des Deutschen Juristinnenbundes e.V. (DJB) zur Konzeption eines Wahlarbeitszeitgesetzes (2016)

- Deutsches Jugendinstitut (2016): „Neue Väter – Legende oder Realität?“ in der Reihe „DJI Impulse“

- Original article in "wissen|leben", Nr. 6, 12 October 2016

- The issues of "wissen|leben" at a glance

- Further information on work-family balance at Münster University